An artistic collaboration for the ages was born because a dentist was too busy. Dr Chataigner could not melt gold for Picasso anymore, and the artist was sick of asking. “Picasso said he could not go on pestering the dentist: the man had teeth to fix,” recalled the artist’s biographer, John Richardson. Chataigner had to use his smelting skills to fill cavities, not make gilded centaurs, and so Picasso needed to find someone else to help him use an ancient medium for which he had many ideas, but no technical expertise.

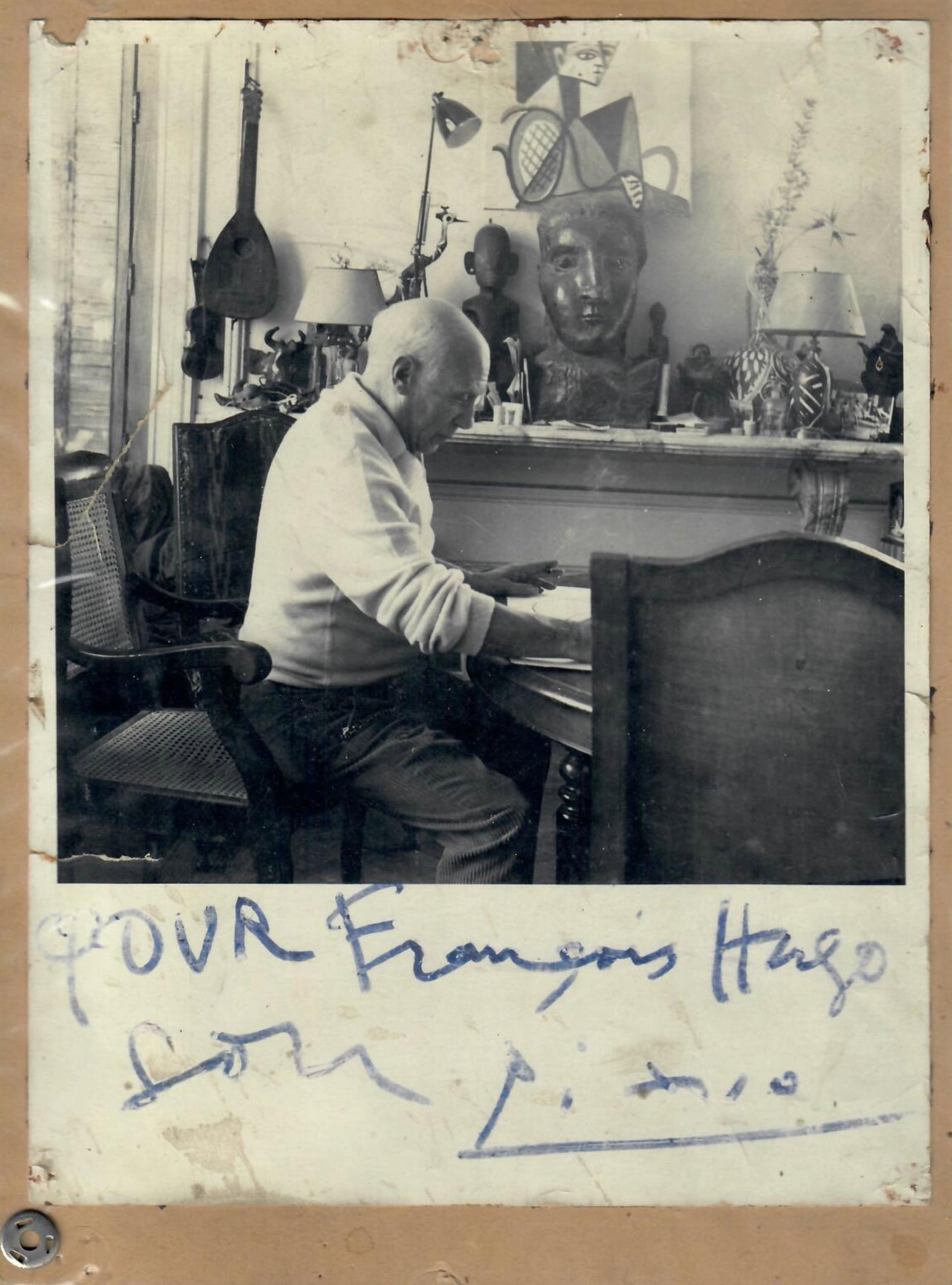

A photograph of Picasso inscribed to François Hugo Courtesy of Ateliers Hugo

During a studio visit in 1956, Picasso asked Richardson who else could execute his designs. The art historian suggested François Hugo, a trained engineer with dexterous hands who had spent the Second World War and the years after making custom buttons for couture designers like Coco Chanel, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Christian Dior. Picasso had known Hugo for years after the two met at the 1917 premier of Parade, a Ballets Russes performance. He contacted François and within months they were working together.

Around ten golden bowls and medallions that Picasso made with Hugo will be exhibited at Barcelona’s Museu Picasso in Picasso and the Artist’s Jewellery, opening in May. In April, the Ateliers Hugo—founded by François and his son Pierre, and now run by 32-year-old grandson Nicholas—plans to release medallions of a masked figure and abstract spiral created with contemporary sculptural painter Josh Sperling, representing the latest in this workshop’s series of artistic partnerships. Taken together, the two events bookend the artistic production of a three-generation family business that has operated from the same studio in southern France for nearly 70 years.

Nicolas with his father Pierre in the Ateliers Hugo workshop, where photos of François and other family hang on the walls Photo: Maxime Souyri. Courtesy of Ateliers Hugo

Like a Renaissance workshop, knowledge of how to spin an artist’s drawing into gold (and which designs would work best) has been passed from father to son. François, a great-grandson of French writer Victor Hugo, knew several artists personally and worked from the house he built for himself just outside Aix-en-Provence. Pierre grew up there, and started apprenticing under his father in his early 20s, after studying at London’s Royal College of Art.

“Basically, it started with Picasso,” explains Nicolas Hugo, who joined the atelier two years ago, after his father became ill and none of his four siblings were interested in entering the family business. “And of course, if Picasso was doing something, everyone wanted to do it as well.” Other artists friends of François’s soon came with their own ideas for collaboration, including Max Ernst, Jean Cocteau, and André Derain. As word spread, he also worked with Jean Arp, Dorothea Tanning, Jean Dubuffet, Jean Lurcat, and Roberto Matta, among others, to make limited edition series. Pierre brought on new artists too, such as Arman and Corneille van Beverloo.

By the time Nicolas joined, the atelier was collaborating with Ugo Rondinone and Eric Croes. The younger Hugo was an independent dealer, selling Modern and contemporary art, but Ateliers Hugo was always in his peripheral vision since he grew up next door to his grandfather. “Our kitchen is five meters from the workshop,” he says. “I’ve seen this work all my life.”

Artist-designed gold pieces created by Ateliers Hugo Photo: Lucillia Chenel & Ken Israel. Courtesy of Ateliers Hugo

Nicolas is bringing the atelier into the 21st century by digitizing its archive, cultivating an online presence (the workshop is now on Instagram), and partnering with new contemporary artists.

His first project has been to work with Sperling, a process that began when the two met through the Belgian gallerist Sebastien Janssen in October 2019. The artist brought several drawings and Nicolas picked two, which Sperling turned into three-dimensional models. Ateliers Hugo transformed the models into prototypes, and after the artist approved them, they were turned into moulds which were used to hammer out the series of medallions.

The shapes of Sperling’s works are new, but their artistry is heirloom. “The house is the same, the tools are the same. The workshop is the same, the technique is the same,” Nicolas says. “Nothing has changed, really. It just has more pictures of the family.”