The book The Van Gogh Sisters, to be published next month, reveals the very different lives of three of Vincent’s siblings: Willemien (Wil), Elisabeth (Lies) and Anna. Written by the Dutch art historian Willem-Jan Verlinden, it will now be available in English.

The Van Gogh family suffered a series of tragedies. Vincent’s brother Theo, who is now remembered as the artist’s staunch supporter, died six months after him, suffering a terrible end with syphilis. Vincent’s youngest brother Cor committed suicide in South Africa during the Boer War—and was the subject of a biography by Chris Schoeman in 2015 called The Unknown Van Gogh. But the three sisters have so far received scant attention from writers, an omission addressed in Verlinden’s study.

Vincent was closest to Wil, his youngest sister. In 1875-76, aged just 13, she spent nine months in Welwyn, a village just north of London, where she learned English and attended a school where her eldest sister Anna was working as an assistant teacher.

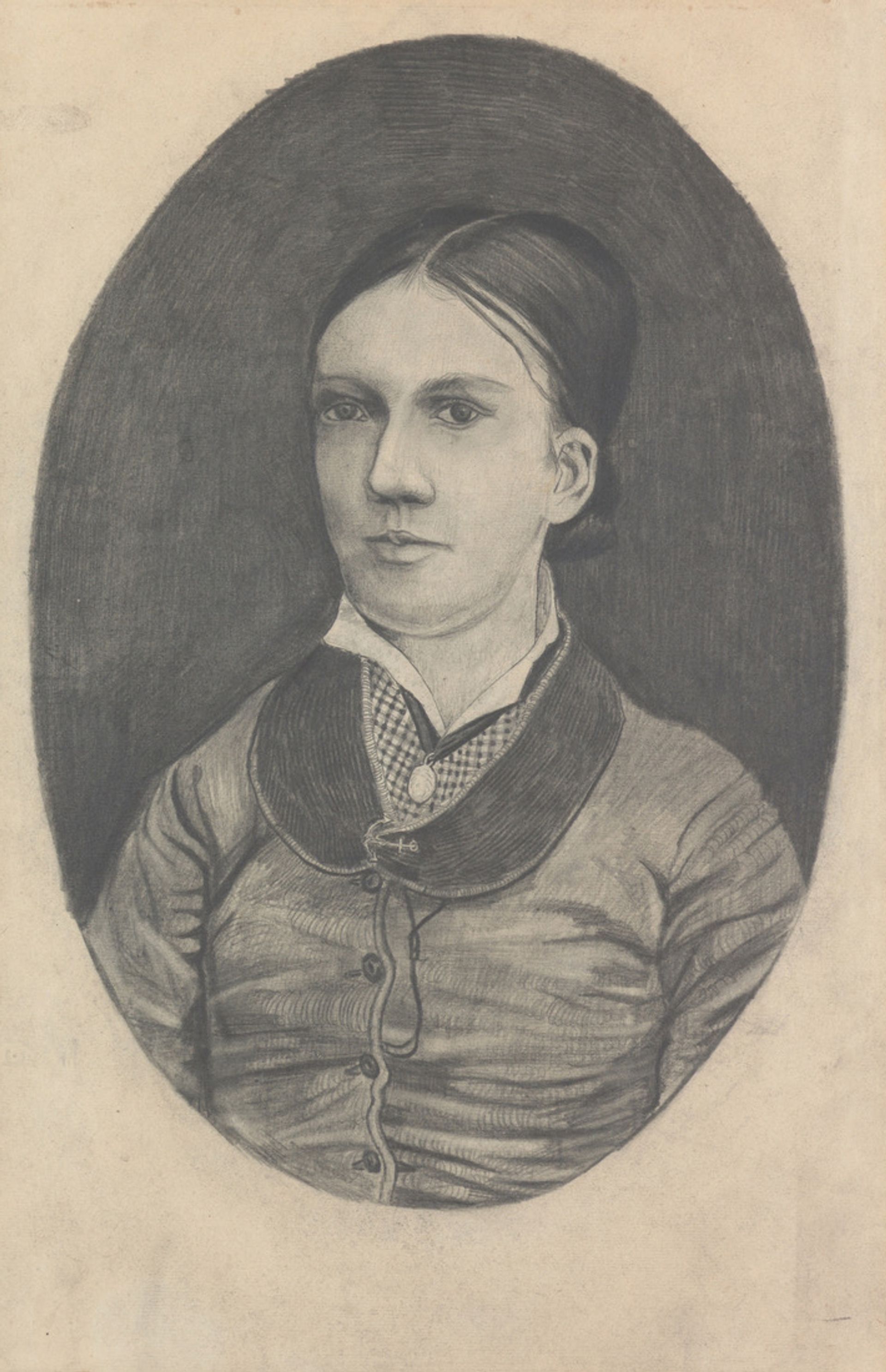

Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Willemien (Wil) van Gogh, aged 19 (July 1881) Courtesy of Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Wil was a sensitive young woman and she had a deep love of flowers and literature. In 1881, at the age of 19, Vincent drew her portrait from a photograph, capturing her serious expression. They corresponded regularly and six years later Wil sent him a short story she had written about “plants and the rain”. Vincent responded that “many a flower is trampled”.

In 1888, while Vincent was living in Arles, he painted what he described as an imaginative “reminiscence” of the garden in the family home. Writing to Wil, he suggested that the two women walking are “you and our mother”. Depicting Wil carrying a red parasol and in what he said was a Scottish plaid shawl, she represented “a figure like those in Dickens’ novels”—a nod to her literary interests.

Vincent van Gogh’s Reminiscence of the Garden, with Wil under the parasol (November 1888) Courtesy of the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Wil, like Vincent, considered various professions—working at times as a governess, florist, nurse and scripture teacher. She ended up becoming involved in the early Dutch feminist movement, initially as a member of a women’s library in The Hague.

More importantly, Wil went on to join the organising committee of the 1898 National Exhibition of Women’s Labour. This was a progressive initiative calling for greater access to education and skills, to encourage the promotion of female workers to more senior jobs. The exhibition and accompanying events were a great success and represented a key step in the development of women’s rights in the Netherlands.

Poster designed by Suze Fokker for the National Exhibition of Women’s Labour (with the beehive symbolising female industriousness), The Hague, 1898

Some months later disaster struck, when Wil began to manifest severe mental health problems. Little is known about her condition, but in 1902, at the age of 40, she was sent to the Veldwijk asylum in Ermelo, east of Amsterdam.

Verlinden quotes her referral letter. Wil was “angry and acts wild... she screams, bites, scratches and throws punches... she refuses to eat and hallucinates”. Her doctor recorded that upon entering the asylum she “spoke of suicide” and some sources suggest that she actually tried to end her life.

Once institutionalised in the asylum, Wil hardly spoke, retreating into herself. Astonishingly, she survived for another 38 years, virtually half her life, dying there in 1941—the last of the siblings.

Vincent’s middle sister Lies also suffered a tragic life. As a young woman she worked as a nurse looking after a woman with cancer and then fell in love with the patient’s husband, Jean du Quesne, a lawyer. In 1886 they had an affair and Lies became pregnant. To disguise the situation Lies initially told her siblings that she was travelling to England for a holiday with a female friend and taking along a canary named Pietje.

Her “friend” was actually her employer Jean. The couple never actually crossed the English Channel, instead stopping near the Normandy coast, where their baby was born in a hotel. They left the female child, named Hubertine, with a young widow who ran the village grocery shop. Lies returned to see her only once, in 1922, by which time her abandoned child was 35. She hoped to bring Hubertine home, but her daughter refused. Lies died in 1936.

Hubertine ended her days as a penniless hawker, selling sweets and stationary in Marseille. She was “discovered” by a journalist in 1965, who revealed her existence, and died three years later in Lourdes. Vincent, who had been living with Theo in Paris in 1886 when Hubertine had been born, may have never have learned that he had a young niece.

Anna, the eldest of the Van Gogh siblings, was the only one of the six who led a relatively normal life. She married, had two children and died in 1930. Anna also kept a loving eye on Wil’s care at the asylum, which was partly funded by the sale of a few paintings they had been given by Vincent.

The fact that three of the Van Gogh children either committed suicide or contemplated doing so suggests a possible genetic medical condition. The fate of the siblings might give some clues as to why Vincent mutilated his ear and shot himself in the chest.

Other Van Gogh news

• Van Gogh’s painting Scène de rue à Montmartre/Montmartre Street Scene (Impasse des Deux Frères et le Moulin à Poivre) was the subject of dramatic bidding at Sotheby’s, Paris on 25 March. The estimate was €5m-€8m. When the hammer went down, an internet bidder won at €14m (€16.2m with fees). But it quickly emerged there had been a problem with the internet bid, and the painting was offered again later in the auction. This time it sold for €11.2m (€13.1m with fees), going to a bid handled in London. There had also been strong competition from a bidder at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, an indication of the current strong East Asian interest in Van Gogh.