Ernesto Mallard, one of the leading figures of the Mexican Op-art movement and an early proponent of Kinetic art, has died, aged 89.

Latin America in the 1960s was generously endowed with Modern artists but Mallard—who did more than anyone else to engage audiences and invite them to explore his three dimensional creations—was the first to cause a sensation and then retreat. He memorably said a line was “created by a dynamic point that generates a plane and then a poem”, and his use unique implementation of this idea in works such as Heliogonia teased the eye and won him critical acclaim.

Originally from the state of Veracruz, Mallard studied architecture at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in the late 1950s and then at the “Esmeralda” National Art School. By the late 1960s, he was producing a number of sculptures and visual art pieces including posters for the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City.

Ernesto Mallard, Heliogonía (triptych) (1968) Museo Amparo, Puebla, Mexico

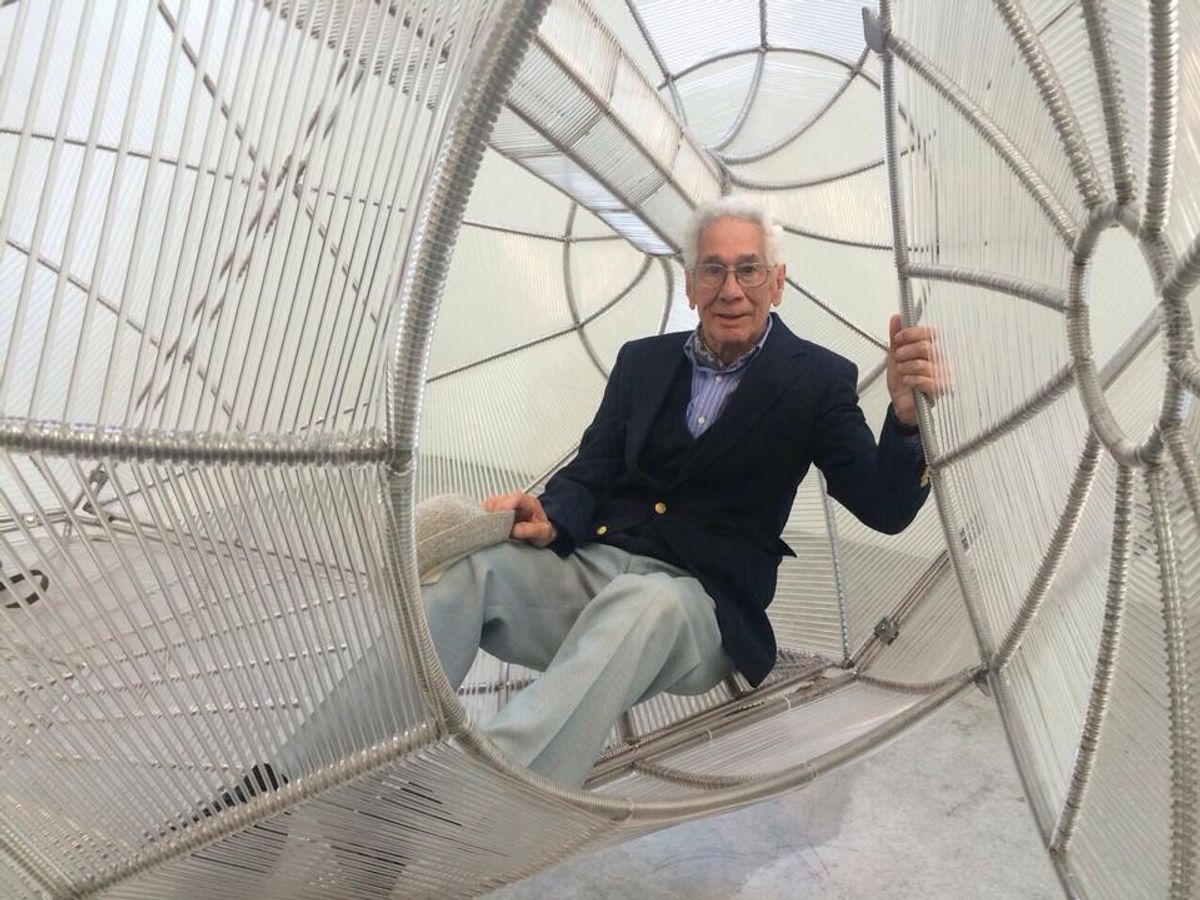

He gained some critical attention that same year in the exhibition Kineticism at the National University Museum of Science and the Arts—the perfect venue for his series of mobile sculptures, which Carlos Pellicer, the poet and former director of fine arts at the National University nicknamed “Naturacosas” (nature things). Mallard thought there was no better way to describe the skeletal hanging pieces made from a range of scavenged and everyday materials and the name stuck.

Then abruptly, in the mid 1970s, he stepped away from the art industry, along with his fellow abstract artists Manuel Felguérez and Sebastián—although they drifted back and earned Mallard’s disdain for doing so.

“He believed in the integration of art in life, and in its liberating potential,” says Abigail Winograd, a curator at the Smart Museum of Art in Chicago. Mallard’s decision to leave the gallery system was due, she adds, “to a realisation that the commercial art world did not share this conviction.”

Pilar Garcia, the curator of the artistic collection at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporaneo (MUAC), which hold several pieces by Mallard, thinks he was perhaps ignored by the Western art community because they could not see beyond the similarly kinetic work of Alexander Calder.

But in 2014, the contemporary Mexican artist Pedro Reyes, who has acknowledged Mallard as his inspiration, persuaded him to dig out his remaining archive and the two held an extraordinary joint show, Connect The Dots, at Labor Gallery in Mexico City. It was Mallard’s first show in 40 years and his work was still very relevant, says Labor’s Pamela Echeverría's. “So much of what he did was ephemeral but seeing it all again was an affirmation—that he had not betrayed himself and never crossed his own line.”