Despite travels bans, quarantines, and more government forms than you could shake a stick at, Saudi Arabia went ahead with its inaugural Noor Riyadh festival last week. The annual event is billed as a festival of light and art, under the title Under One Sky (until 3 April). Works are spread out across the capital city and sit mainly in two camps: crowd-pleasing spectacle and those with a more contemporary art pedigree.

“This is one of the largest art movements since the Renaissance,” says Hosam Al Qurashi, a senior advisor for the Royal Commission for Riyadh City (RCRC), describing Saudi’s investment in art infrastructure. “We haven't seen a movement like this in hundreds of years. We’ve seen it in Florence or Siena, across Europe, but this is huge, and we're not treating it like a project. This is something to stay.”

Koert Vermeulen's Star in Motion (2021) Courtesy the artist. Photo: © Riyadh Art 2021

In the Matryoshka-doll-like layout of Saudi government departments, Noor Riyadh sits like this: it is one of 13 new initiatives of Riyadh Art, which is itself one of four new programmes for the city planned by the RCRC, alongside increased sports facilities and green spaces. The RCRC is an existing government department that has been renamed as part of the country’s Vision 2030 reforms.

“Riyadh aims to become one of the top ten city economies globally,” says Al Qurashi. “That means quadrupling our GDP, but also significantly improving our quality of life. Saudi art plays a massive and important role in beautifying the city.”

Daniel Firman's Butterfly (2007) Courtesy of the artist and the Farjam Collection. Photo: © Riyadh Art 2021

The choice of Noor Riyadh’s venues provided a glimpse at the Saudi initiatives to come, such as the enormous JAX warehouse district, or the historic Ad Diriyah Palace—one of the venues for Riyadh’s upcoming biennial—which will also have an adjacent art district.

For these initiatives, as for Noor Riyadh, the goal is to both support the arts and to leverage them to attract tourists and residents—helpful if Saudi is to meet Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s recent directive that all foreign executives of Riyadh businesses must live in the capital by 2024, rather than flying in and out of regional hubs such as Dubai.

Daniel Buren's Colored Triangles by Myriad, for Riyadh work in situ at the KAFD Conference Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Courtesy of the artist and GALLERIACONTINUA. Photo: © Riyadh Art

The festival is spread across 13 venues, with the exhibition Light Upon Light: Light Art Since the 1960s anchoring it in a conference centre attached to Riyadh’s new King Abdullah Financial District. The venue had a bit of the old Saudi make-do infrastructure about it, squatting within a temporary exhibition structure on the floor above an AMC cinema. It had a bit of the new Saudi too, with its hyper-investment in art: the centre’s vast, multi-peaked glass roof was festooned by a Daniel Buren artwork made up of nearly 10,000 coloured triangles (Colored Triangles by Myriad, for Riyadh, 2020-21).

Other works across the city were deliberately more accessible, as cultural agencies navigate a public unused to contemporary art.

A video projection of patterns used to decorate traditional houses by the artist Ali Alruzaiza Tribute to Ali Alruzaiza, 2021. Video design by Sara Caliumi and Carlo Camorali. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: © Riyadh Art

“We’ve done a lot of focus groups, we've talked with the community to learn about what it is that they want to see in the neighbourhoods,” says Miguel Blanco-Carrasco, the Spanish-born executive director of Noor Riyadh. “A light festival was a really clear decision because light is a universal language everybody can understand. You don't have to be an expert in contemporary art, you don’t have to have a PhD in history of art, to understand the pieces we've seen.”

The agencies seem to be betting that time and increased exposure to the kingdom will wear down any Western qualms about engagement with the country, whose human rights record is a frequent source of objection. Unlike last year's Desert X Al Ula, when three of the California biennial’s board members resigned over the Saudi edition, there was no rumble of dissent over Noor Riyadh—despite the participation of a number of high-profile artists, or their estates or lending bodies, such as Buren, Dan Flavin, Nancy Holt or Robert Wilson.

Nancy Holt's Holes of Light (1973) Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation with support from Holt-Smithson Foundation. Photo: © Riyadh Art 2021

Most of the big international names were shown in a quick-romp historical section of Light Upon Light, which was strongest when it left this survey behind and turned to Saudi makers. Bucking a trend of chasing the new, Noor Riyadh's artistic director Sumi Ghose and the Light Upon Light curators Raneem Zaki Farsi and Susan Davidson made the decision to include older Saudi works. While Saudi artists are still overwhelmingly young, most have now been working and exhibiting for at least a decade.

Maha Malluh showed her photograms of personal objects whose importance has been challenged by consumerism, Capturing Light (2005). Ahmed Mater featured his neon version of a TV aerial, Antenna (Green) (2010), which he used to try and get TV signals from neighbouring Sudan while he was growing up. Younger artists also operated in a spirit of reclamation of the past, such as Abdullah Al Othman and his neon sign, Casino AlRiyadh (2021), which commemorated an early social club in the city.

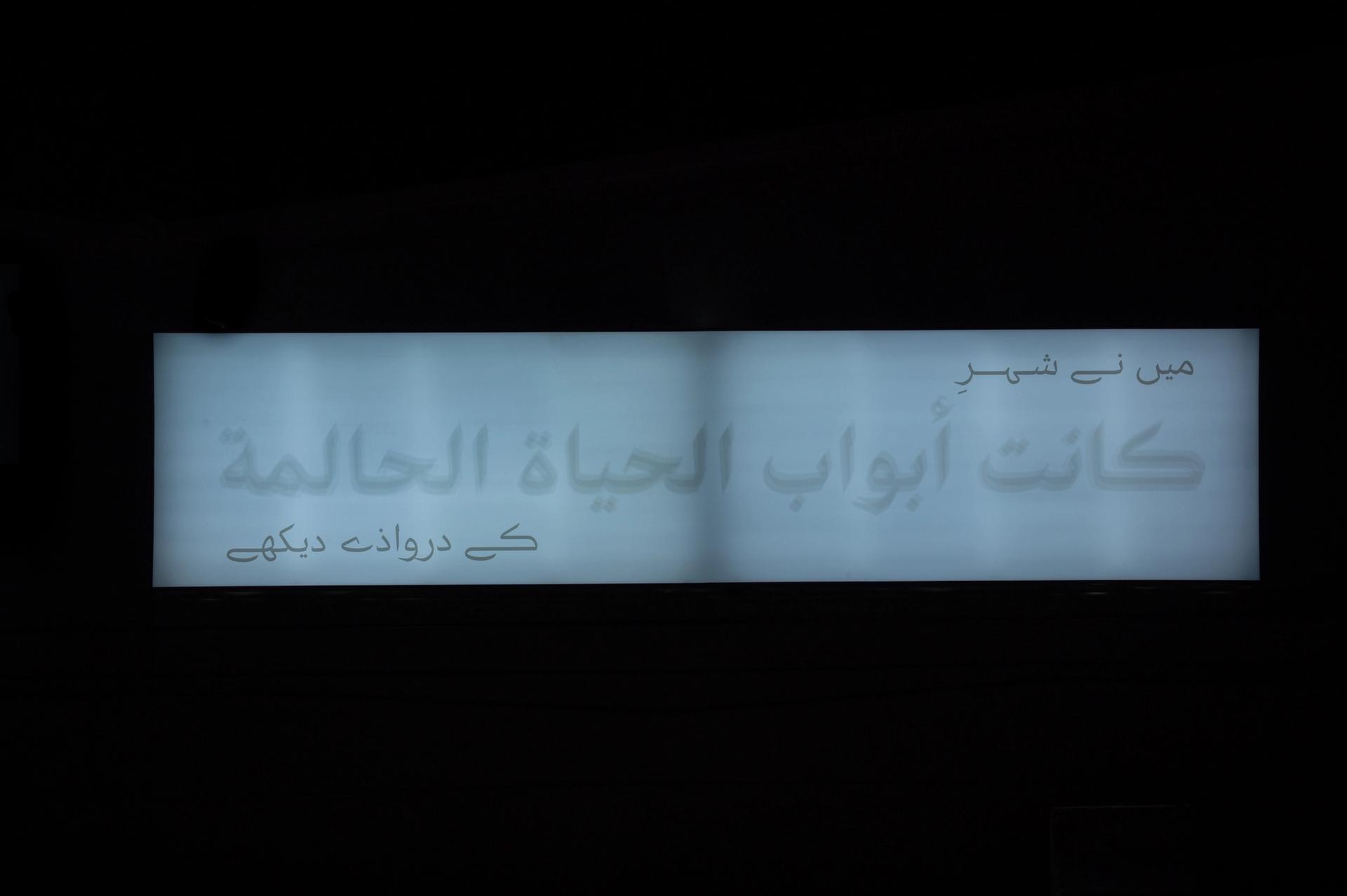

Nojoud Alsudairi's رسائل مؤقتة, Ricochet (2021) Courtesy of the artist. Photo: © Riyadh Art

And while not perfect, other festival works sought to engage the diversity of Riyadh, reaching out towards its Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Filipino communities—a public overture that would have been radical a decade ago. Marwah Al Mugait showed the multilingual video May We Meet Again (2021) in a park typically frequented by migrant workers. For Ricochet (2021), the architect and artist Nojoud Alsudairi crowd-sourced phrases about Riyadh from a cross-section of its residents, imprinting them on coffee cups that were sold in pop-up coffee bars throughout the city.

“I have no other place,” one read simply. Whether due to economic necessity or neighbourly competition, Saudi is holding its course.