“If ever there was a time to invest in mental health, it’s now,” urged the director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, in a video address last May. As governments around the world struggled to limit the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic with mass lockdowns, the head of the United Nations (UN) health authority warned of a parallel global threat: the risk of social isolation and a predicted rise in mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.

Now, the WHO is backing a year-long fundraising campaign to mobilise the art world in its emergency response to this “mirror pandemic”. Through a series of charity auctions in partnership with Christie’s and the nomadic social enterprise Culturunners, the Healing Arts initiative aims to raise $15m in aid of the WHO Foundation and a new fund for artist-led projects that contribute to improved mental, social and environmental health in the wake of Covid-19.

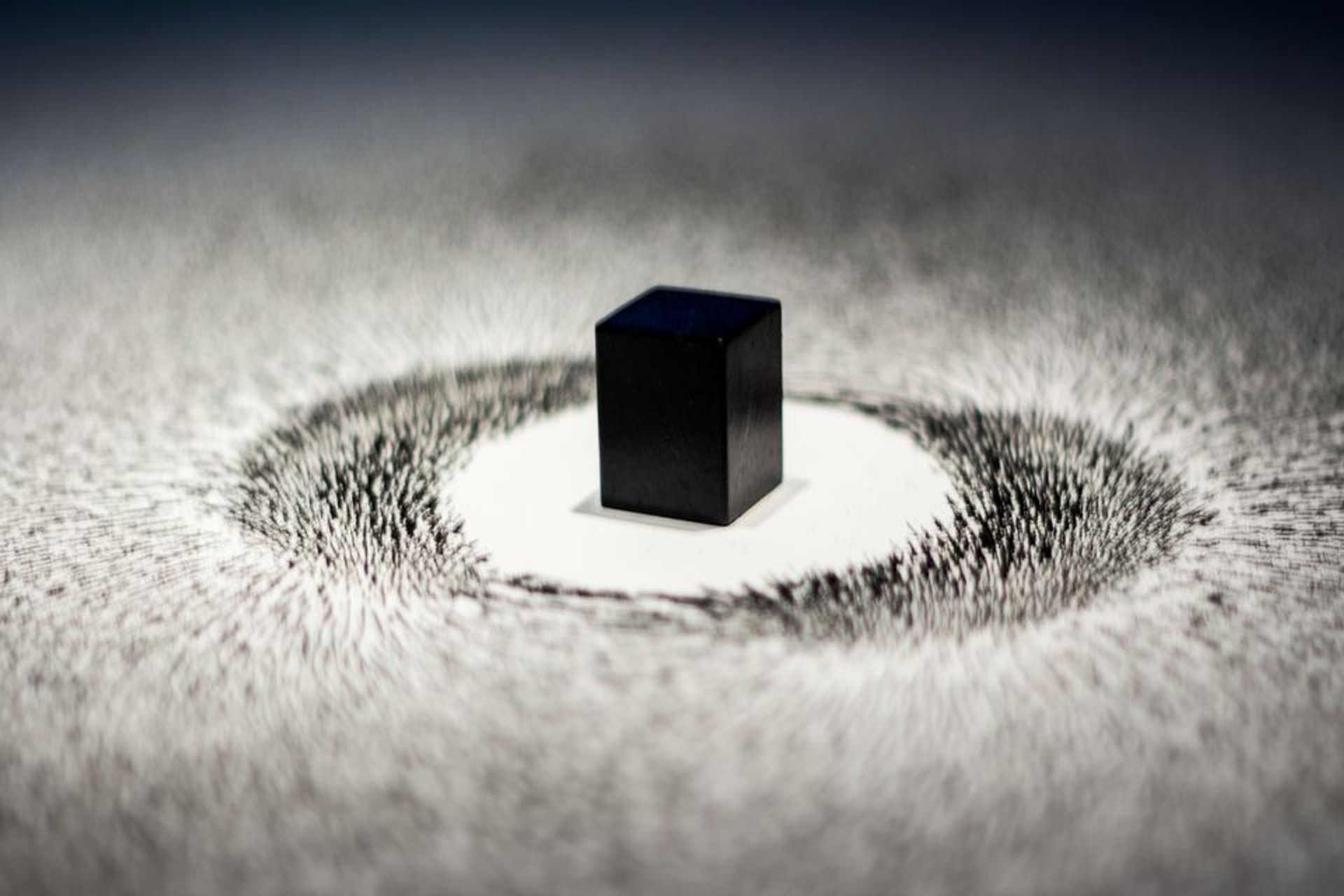

The sales began last November with the £100,000 hammer price achieved for Magnetism (2009), an installation evoking the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in miniature, with a congregation of iron filings orbiting a cuboid magnet, donated by the Saudi artist and trained doctor Ahmed Mater. They continue on 25 March, when Christie’s London will offer works donated by Martin Creed, Antony Gormley and Ragnar Kjartansson, among others.

Ahmed Mater's installation Magnetism (2011) Photo: Hans Splinter via Flickr

With further auctions set to follow throughout 2021, part of the proceeds will support mental health treatment and recovery including the applied use of the arts, via the WHO Foundation, an independent grant-making entity set up to promote philanthropy for the WHO. A portion of the funds will establish a socially engaged “artist response fund” as part of The Future is Unwritten, a collaborative initiative launched last year as part of the UN’s 75th anniversary programme, UN75, that harnesses the arts in advocating for the UN’s 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

This is a call to action for artists and art organisations to join forces with health professionals at a time of global crisis, says Stephen Stapleton, the founding director of Culturunners. If the shock of the pandemic has upended the “hectic glamour” of the art industry and sent museums into shutdown, it has also forced an existential reckoning with the core value of art, he argues. “It’s not about bailing out the arts, but understanding that the arts are fundamental to our society,” he says. “A society without the arts is not a healthy one.”

Art’s “healing power” lies in its capacity to tell human stories, stir emotions, inspire empathy and navigate complex situations and emotions, says Christopher Bailey, the WHO’s arts and health lead and co-organiser with Stapleton of the Healing Arts initiative. “It’s essential for a holistic view of the world. If you only focus on scientific method, you lose emotional context—the way we’re neurologically evolved to contextualise the world.”

Having started his career as an actor and theatre director, Bailey has brought his unconventional background into major public health campaigns at the WHO—for instance, applying improvisation and role-play techniques in his presentations of electronic medical record systems at rural East African clinics. His combined arts and health remit at the WHO developed in 2019 out of the director-general’s request for “crazy ideas” from staff about how to transform the organisation. Bailey’s “elevator pitch” centred on the importance of empathy, in addition to scientific rigour, “in changing people’s minds and behaviours”.

The director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has warned of the mental heath impacts of Covid-19 © Elma Okic

When the pandemic hit, it was another staff idea that prompted One World: Together at Home, a marathon livestreamed concert last April by Lady Gaga and more than 100 musicians performing from their homes. It raised $127m in philanthropic and corporate donations for coronavirus relief efforts, including $55m for the WHO’s fund to supply PPE and develop tests and vaccines. Bailey, who was part of the team that organised the concert, describes it as “the message that needed to be heard” early in the pandemic, rallying solidarity with health workers and promoting Covid-19 safety measures “in an entertaining and authentic way”.

But as the months of restrictions have worn on, a “silent or second pandemic” has emerged, he says: the mental health toll of isolation, stress and bereavement, affecting young as well as old. The launch of Healing Arts can be a “Trojan horse” in this new priority area, he thinks, “not just raising money but telling the story of the power of art in health”.

Policy awareness gap

There is considerable evidence to support that premise. In 2019, the WHO’s Regional Office for Europe released a report by University College London (UCL) researchers Daisy Fancourt and Saoirse Finn that synthesised 3,500 academic studies published since 2000 on the health benefits of the arts. Their review found that participation and engagement with visual and performing arts, cultural events and other creative pursuits have a “robust impact” on both mental and physical health. Documented mental health benefits include enhancing wellbeing, reducing stress and trauma, and helping people experiencing mental illness.

The Healing Arts initiative addresses the mental health toll of isolation, stress and bereavement brought by the pandemic © Silvision

One aim of the report was to close what the authors called an “awareness gap” that has led to inconsistent policies across European countries. Many governments “have not yet addressed the opportunities that exist for using the arts to support health”, they wrote, concluding that closer collaboration between the sectors “should be of mutual benefit” internationally. The report was a “milestone” contribution to the research agenda, says Bailey, who is now working with the WHO’s mental health department to develop more focused research studies on the therapeutic use of arts for specific population groups, such as young people and people living with dementia.

Bailey and Stapleton also hope to drive policy discussions with a programme of virtual events in the week of the Christie’s London auction. This will be a “deep dive into the UK experience” of arts and health, Bailey says, heralding further city “activations” planned at the Venice Architecture Biennale in May, in Aspen in July and during the UN General Assembly in New York in September. Participating in the talks are the actor and mental health advocate Gillian Anderson, the former politician turned prison chaplain Jonathan Aitken and a panel of experts working to launch the UK’s National Centre for Creative Health (NCCH) this month.

A still from Ragnar Kjartansson's 2018 video Figures in Landscape (Friday), which will be offered at auction by Christie's on 25 March in support of the Healing Arts campaign

Champion for the field

A registered charity supported by the Wellcome and Paul Hamlyn foundations, the NCCH fulfils a key recommendation of the Creative Health inquiry held in 2015-17 by an all-party parliamentary group. According to its chair, former arts minister Alan Howarth, “there needs to be an organisation that will take an overview” and “encourage intensive experimentation” in regions that are already pioneering models of arts-based health and social care. Independent from government, the centre will act as a “champion for people in the field”, he says.

It also takes up the core argument of the Creative Health inquiry that the arts could relieve the overburdened National Health Service (NHS) by addressing challenges relating to ageing, loneliness, mental health and long-term health conditions—ultimately saving public money.

For now, there are pockets of “excellent practice” in the UK, Howarth says, but they are all too reliant on “individual enthusiasts”. It will take a sea-change in attitude among politicians, senior health officials and even trainee doctors, he suggests, until the “whole medical culture has recognised the potential in the arts”.

On the flipside, recent years have seen rapid growth in “grassroots” efforts around arts and health from the cultural sector, says Victoria Hume, an adviser of the NCCH and the director of the Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance (CHWA). Supported by Arts Council England, the membership network represents around 6,000 organisations and practitioners—numbers that have swelled by “4,000 in two years”, she says. The momentum “has only increased through Covid-19 because the links between creativity and health are so clear”.

For these small organisations, the crisis spurred a “surge in innovation” as they rallied to support their local communities, Hume says, but it also worsened “the precarity that was always an issue in the sector”. CHWA’s 2020 surveys of its members have raised “huge concern” about the lack of support for freelancers who are the “backbone of the sector”, as well as the “hand-to-mouth” model of short-term project funding—mostly from charitable foundations. “It can feel like being stuck in a pilot phase,” she says.

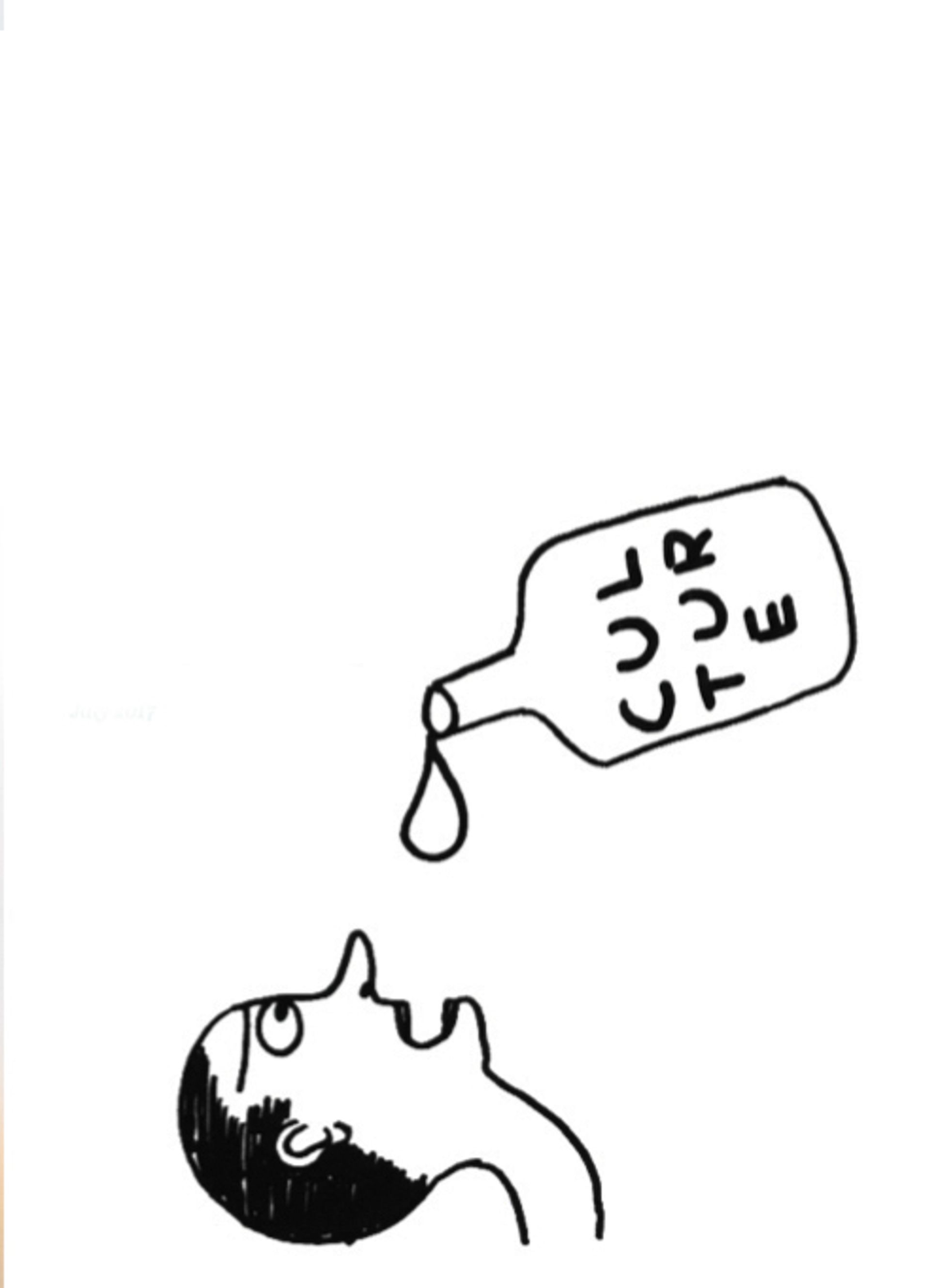

The UK’s Creative Health Inquiry concluded that the arts could play a role in unburdening the health services. The artist David Shrigley illustrated the cover of the inquiry’s report David Shrigley

Fundamental culture shift

Observers agree that sustainable funding and partnerships will be critical for the future of creative healthcare in the UK. “So much of the work we do around health and wellbeing is incremental—it’s about very long-term sustained relationships,” says Esme Ward, the chair of CHWA and the director of Manchester Museum. Since her appointment in 2018, she has led a vision to transform it into the country’s “most inclusive, imaginative and caring museum”.

Ward likens museums’ increased emphasis on community wellbeing today to the burgeoning of educational outreach in the 1990s. The devastation of Covid-19, and the wave of mutual aid it has inspired, have “accelerated a fundamental culture shift” at Manchester Museum, she says, “placing care as foundational to the future as much as education and all the other things we do”. At press time, the museum was closed to the general public amid England’s third national lockdown, but it continues to host Project Inc, a social enterprise running creative learning programmes with neurodiverse young people. Although Ward admits that her staff are “stretched” in the middle of the museum’s £14m capital project, she asks: “If we don’t do this work now, what are we for?”

Similarly, Jen Ridding, the head of public engagement at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, part of the University of Birmingham, says the gallery felt a “sense of responsibility” to help local residents through “some of the crises on our doorstep”. The Barber is using a £40,000 grant from the Art Fund to launch a 2021 health and wellbeing project including a “nurse in residence”. Jane Nicol, a senior lecturer at the university’s school of nursing and a specialist in palliative care, will lead community workshops about death and bereavement based on the gallery’s art collection, in collaboration with local charities, hospitals and doctors’ surgeries. “It’s about how our collections thrive and have that relevance, embedded in communities,” Ridding says.

Nursing students discuss the collection at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, which has appointed a “nurse in residence” to lead workshops as part of a new community health and wellbeing project Photo: Courtesy of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts

The project will also explore the possibility of making the gallery’s programmes available to patients on prescription—a practice known as social prescribing. Primary care doctors and nurses in the NHS can refer people to non-clinical community activities to improve their wellbeing, particularly if they have mental health or chronic conditions. A prescription might involve gardening, cookery, sports—or the arts.

In 2018, the then UK prime minister Theresa May identified social prescribing as a key pillar of the government’s five-year “loneliness strategy”. The current health secretary, Matt Hancock, set up the National Academy for Social Prescribing in October 2019. The practice offers “fantastic” potential, Hume says, but she cautions that “so far, we haven’t seen substantive funding for the third sector”.

There is “huge appetite” from the arts sector to join social prescribing schemes, but the “biggest challenges are scaling that up and funding it”, agrees Helen Chatterjee, a founding trustee of the NCCH and a UCL biology professor who led an award-winning 2014-17 study of social prescribing in museums. However, given proper investment, she believes the practice could play a crucial role in tackling the health inequalities that have only widened during the pandemic.

After a year that has been characterised by an outpouring of social justice protest as much as pandemic anxiety, the nexus of arts and public health also opens an opportunity to advance equity in the cultural sphere. Health inequalities will be a priority area of the NCCH, Howarth says, because the arts have “too often failed” to reach beyond the privileged few.

“One of the beauties of the engagement of arts in health is that it offers access to the arts to people who typically don’t have it,” he says. And for artists? “An extended audience”.

• The Art Newspaper is media partner to the WHO-backed Healing Arts initiative, which launches in London with a week of online talks and events (22-26 March), including Christie’s special fundraising auction.