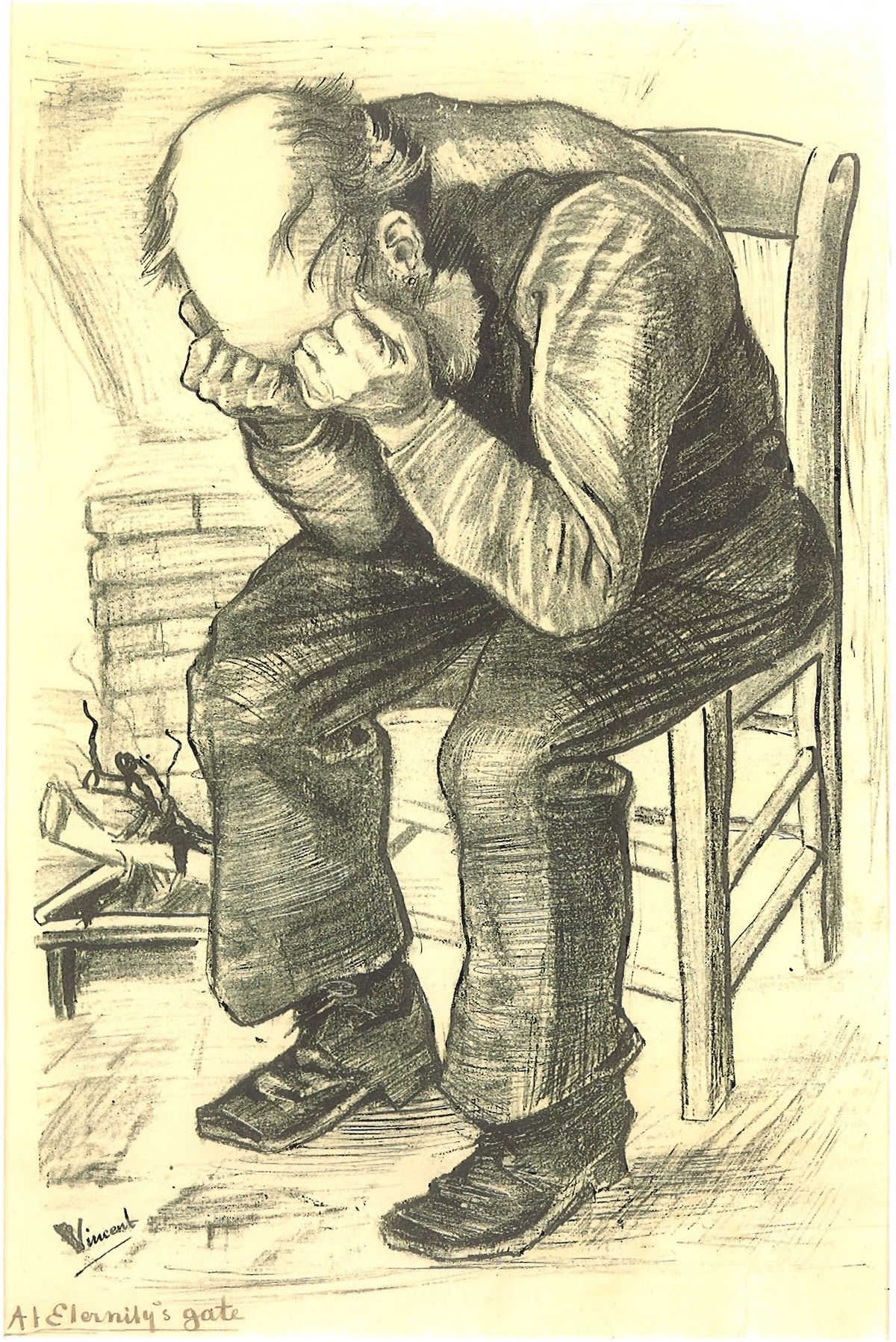

Van Gogh’s print of an elderly man with his head buried in his hands is very rare, with only seven examples surviving. On one of them, he added the inscription “At Eternity’s Gate”—suggesting that the sorrowful soul did not have long for this world. Vincent wrote the title in English because he was seeking work in London.

A new book reveals details of the Van Gogh print’s journey to Iran. Donna Stein, author of The Empress and I (published by Skira on 30 March), writes about her role in advising the Shah’s wife on the establishment of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, which opened in 1977. This bold venture would soon become a victim of political change, as Islamic fundamentalists overthrew the Shah.

At Eternity’s Gate, dating from November 1882, depicts what Van Gogh called an “orphan man”—a resident of an old men’s home in The Hague, where he found models at a time when he was teaching himself to draw. Vincent gave the lithograph with the inked inscription to his Dutch artist friend Anthon van Rappard, who died tragically young in 1892.

Stein reveals that the print was eventually acquired by the fabulously wealthy New York businessman Nelson Rockefeller and his first wife Mary. Rockefeller, who served as US vice president in 1974-77, sold the Van Gogh to the New York dealer Eugene Thaw.

From 1975-77 Stein, a former curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, was employed by the Iranians to advise on acquisitions for the planned Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. She found the Van Gogh at Thaw’s gallery, on sale for $65,000.

Although the Van Gogh market is now truly global, at that time there was little of his work outside Europe and North America—so Tehran’s 1975 purchase was remarkable. Stein tells us that she had originally hoped that At Eternity’s Gate would be a springboard for an even more ambitious Van Gogh purchase for the new museum.

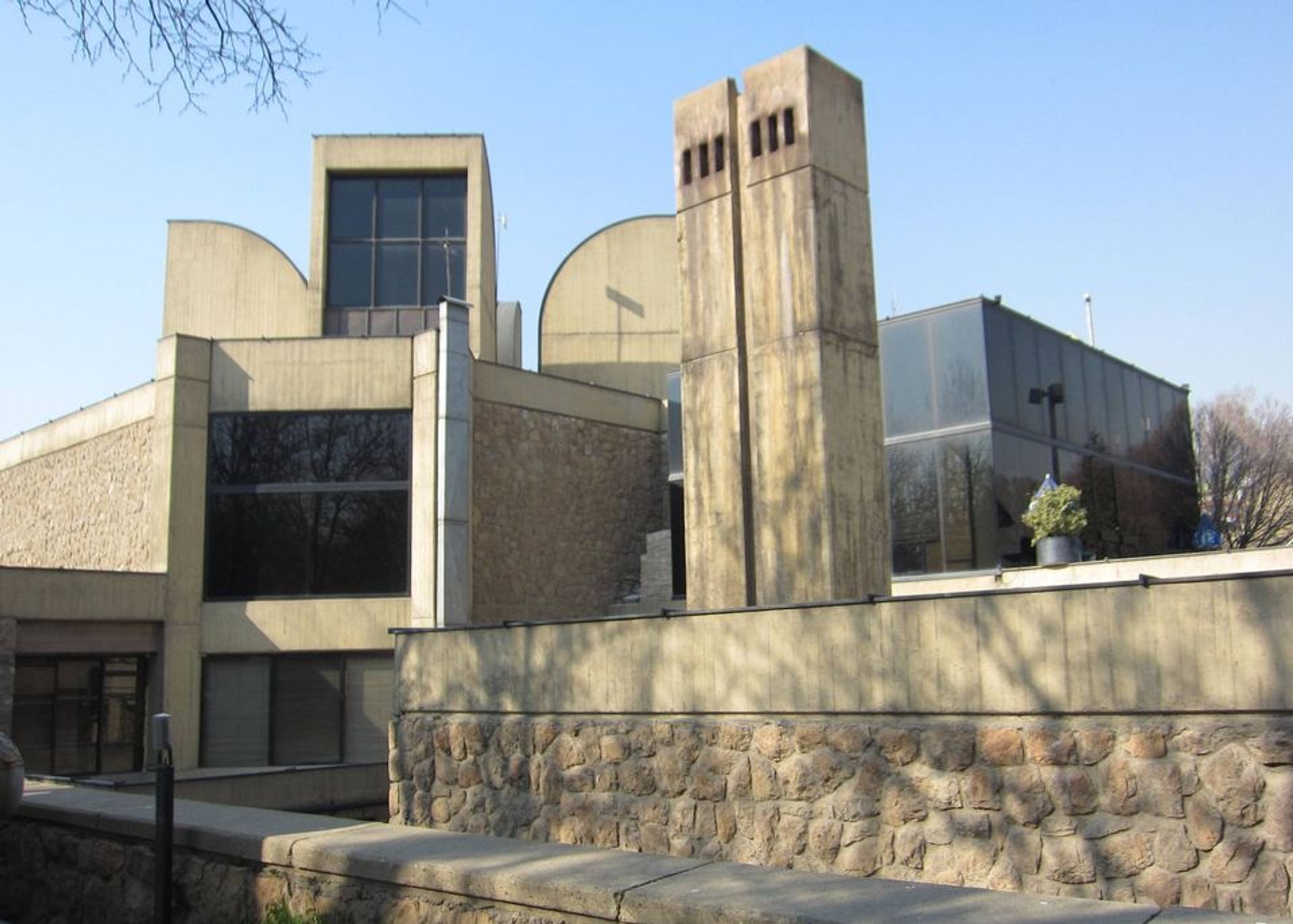

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was an pioneering initiative taken by the Shah’s wife to encourage the modernisation of Iranian society. The idea was to buy fine works of late-19th- and 20th-century Western art and to display them alongside those of Iranian artists. Using Iran’s vast oil wealth, the collection would include pieces by Gauguin, Munch, Kandinsky, Ernst, Giacometti, Moore, Rothko, de Kooning and Bacon.

The Tehran museum opened in October 1977 and the VIP guests included Rockefeller, who had stepped down as vice president earlier that year. Stein still vividly recalls escorting him around the display, which included his former Van Gogh.

But just as the museum was opening, protests were escalating over the Shah’s autocratic rule. In January 1979 the emperor was finally overthrown, fleeing into exile. Although the Shah died the following year, empress Farah—the founder of the museum—still lives in Washington, DC and Paris.

The museum’s collection had been removed from the walls in 1978, just a few months after the grand opening, and secured in the basement stores to prevent it from being damaged or looted during the anti-Shah protests. After Ayatollah Khomeini assumed power the following year the art remained hidden away. There were strong anti-Western feelings in Iran and the fundamentalist government considered some of the artworks indecent.

Iran has since liberalised to a considerable degree and in recent years the Western art has partly gone back on display—including, occasionally, At Eternity’s Gate. In 2016-17 an exhibition of the Tehran collection was arranged for Berlin and Rome, but a few weeks before the scheduled opening the Iranian government refused to allow it to go ahead.

As for Van Gogh, his early ambition was to find work drawing images for one of the English weekly magazines, ideally The Illustrated London News or The Graphic. In December 1882 he had written to Theo, saying that “if I went to England and tried right and left, I would indeed have a chance of finding a place”. But he was deterred by “all those editors and having to present oneself there—bah! I shudder at the thought”.

Vincent also wrote to his friend Van Rappard, explaining that if he produced lithographs “this will enable me to apply for work, in England… One has more chance of success if one can immediately show work, for instance by sending proofs of lithographs, than if one has to get by with words alone”.

Van Gogh may well have sent inscribed copies of At Eternity’s Gate to The Illustrated London News and The Graphic. But if so, he never received positive responses—and the prints from this unknown Dutchman were presumably discarded by the London editors.

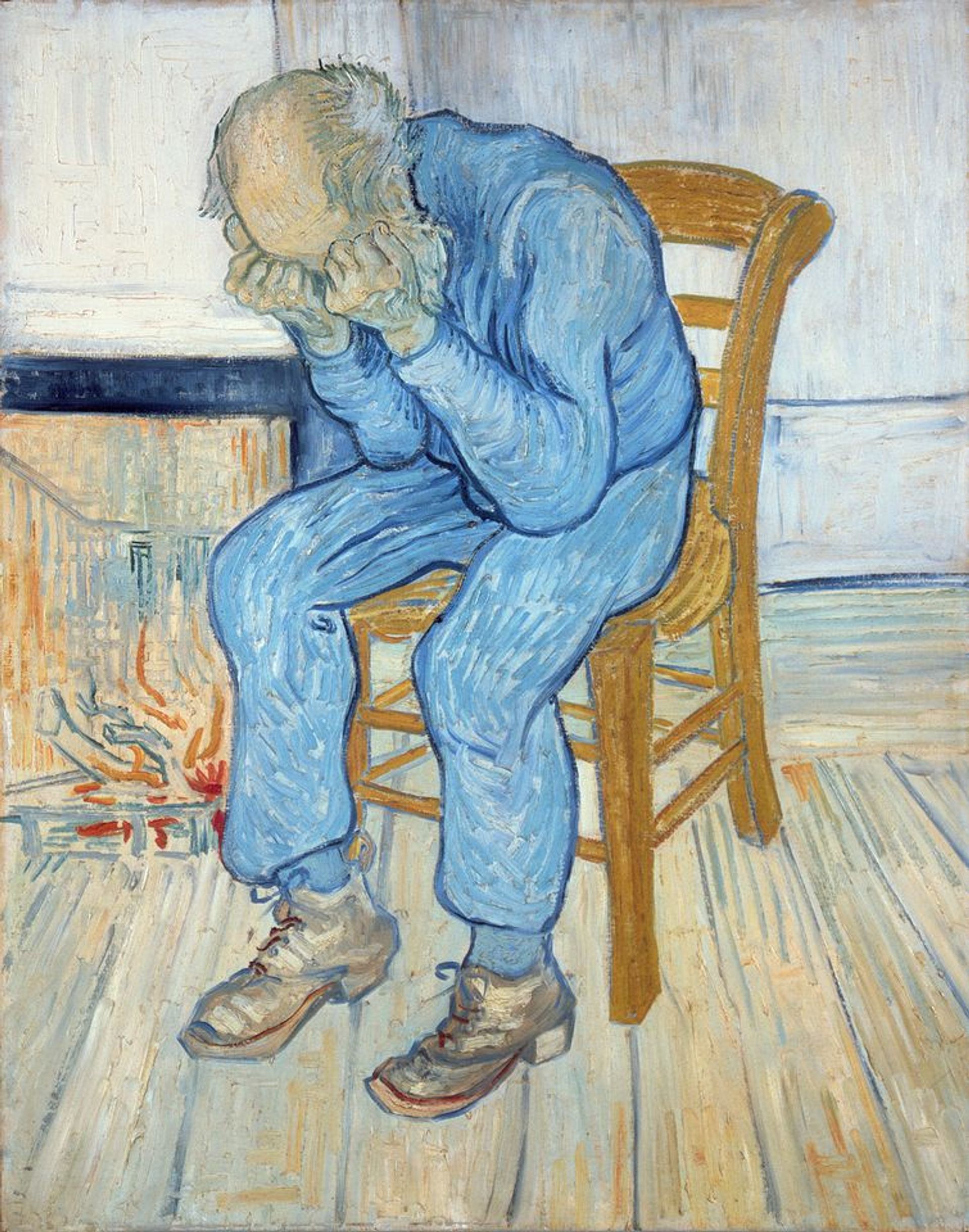

After failing to find work as a graphic artist, Van Gogh decided to turn to painting. Seven years after making his print of At Eternity’s Gate, he used the lithograph as an inspiration, enlarging the image and using oil paints. Vincent described the process: “It’s not copying pure and simple… It is rather translating into another language, the one of colours.”

Vincent van Gogh’s painting At Eternity’s Gate (May 1890) Courtesy of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Two years ago the US artist Julian Schnabel took Van Gogh’s title of the early print and late painting—translating the ideas into his popular film At Eternity’s Gate.

Other Van Gogh news

• The Noordbrabants Museum in ’s-Hertogenbosch (Den Bosch) is about to open a new permanent gallery devoted to Van Gogh, who spent his childhood and early years in the southern Dutch province of Brabant. The display will include 12 Van Gogh paintings (five acquired by the museum and seven on loan from other Dutch collections), along with rare documentary material.

Dutch museums are currently closed because of Covid-19, with an announcement expected from the Dutch government next Tuesday on possible reopening plans. In the meantime, the Noordbrabants Museum will release a digital tour of the Van Gogh display on 26 March.

The new Van Gogh display at Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch Courtesy of the Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch; photo: Jan-Kees Steenman