For more than half a century, Alan Bowness was a leading public figure in the art world in Britain, predominantly as writer, lecturer, curator, administrator and philanthropist. He was the first trained art historian to become Director of the Tate Gallery, in London, where he made an invaluable and lasting contribution in the relatively short time that he held the post.

Bowness was born in London in 1928, educated at University College School, London, following which he did his National Service in the Friends’ Ambulance Unit. In 1950 he went up to Downing College, Cambridge, to read modern languages. From 1953 to 1955 he studied French painting under Anthony Blunt at the Courtauld Institute of Art. In 1957 he joined its staff, teaching 19th and 20th-century art. He became, successively, Reader, Professor and, finally, Deputy Director. In his 23 years at the Courtauld he taught a generation of students, many of whom later distinguished themselves in university or museum posts.

Much of Bowness’s career before his appointment to the Tate was dedicated to making Modern art a serious subject for academic study. In addition to teaching, he published art criticism and curated numerous exhibitions of Modern and contemporary art. The most influential was 54:64 Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, which he curated with Lawrence Gowing. Held at the Tate in 1964, this survey of over 350 works by 170 artists introduced the public to the latest in painting and sculpture from America, Europe and Britain. The show attracted over 100,000 visitors.

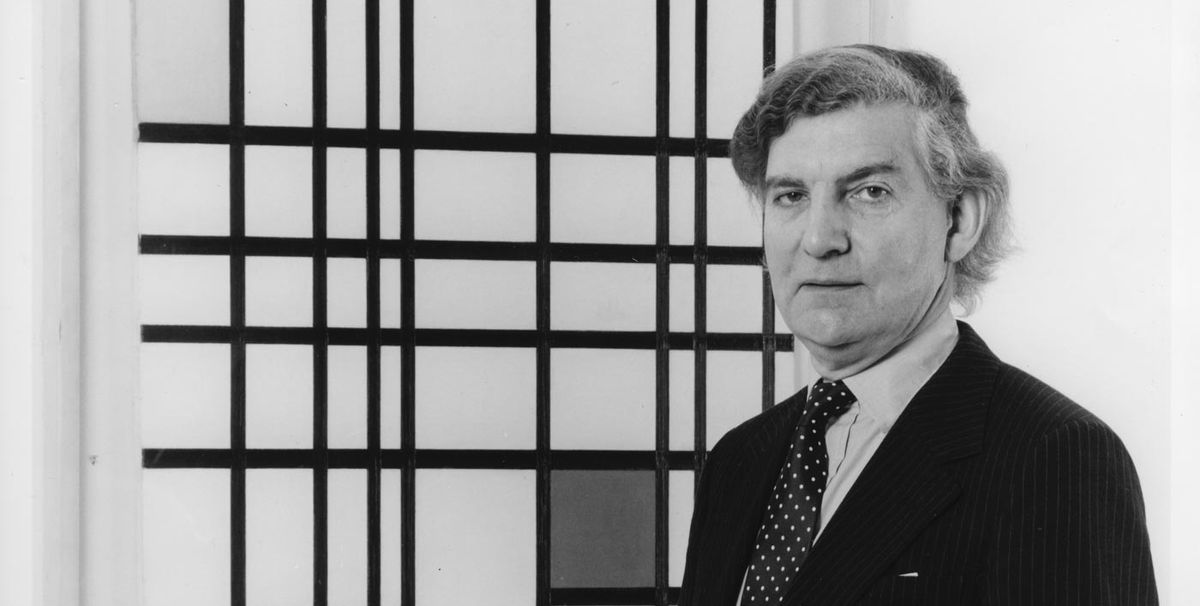

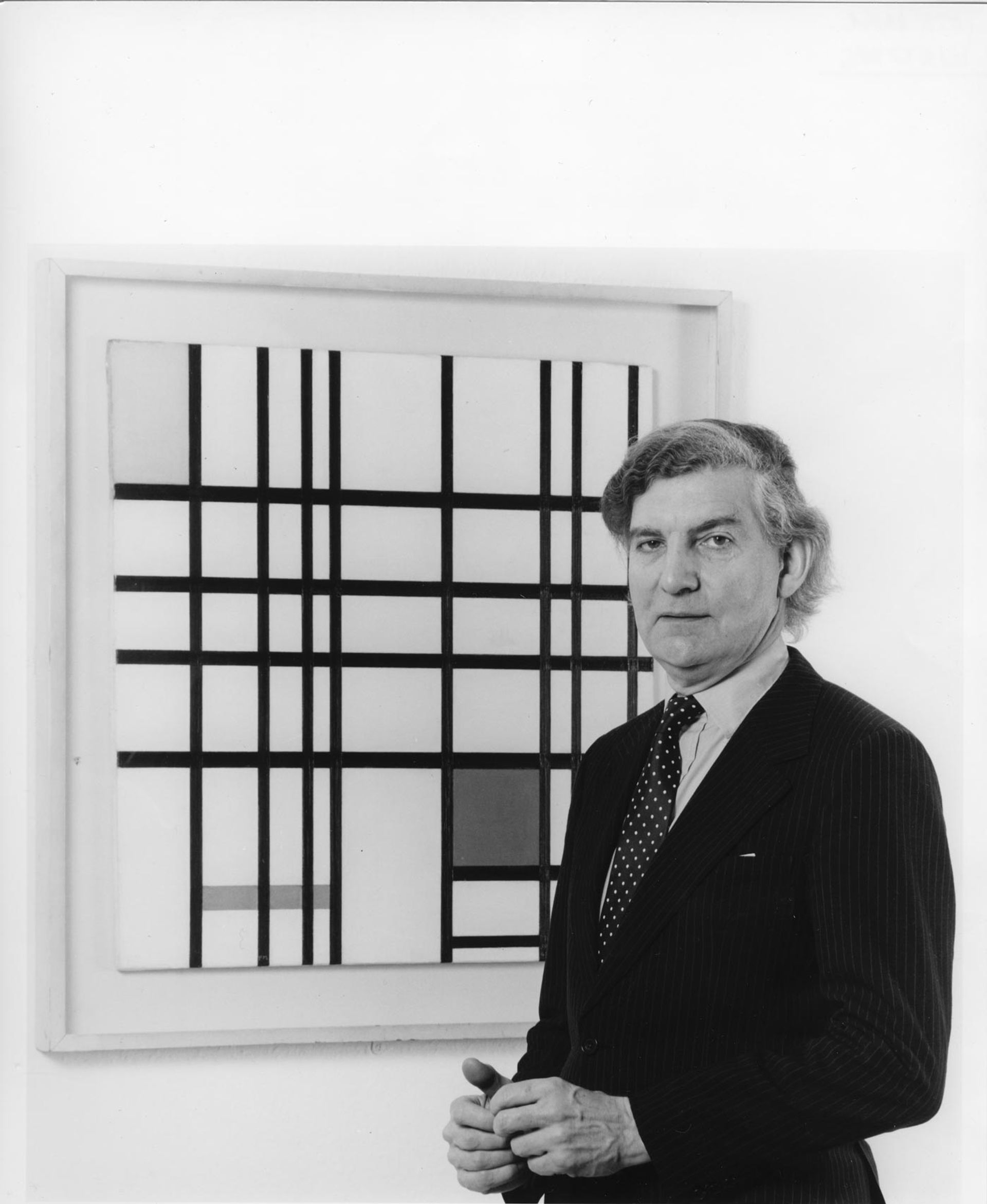

Alan Bowness with Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Yellow, Blue and Red at the Tate, 1980

This international outlook informed almost everything Bowness achieved at the Tate. During his stint as director (1980-88), he founded the Patrons of New Art and the Patrons of British Art, groups of collectors who, based on the American model, assisted the gallery with funding for acquisitions and exhibitions. He also established the Turner Prize, which, if nothing else, has helped raise public consciousness of contemporary art to an unprecedented level. The two main capital projects he initiated were the Clore Gallery for the Turner Bequest, uniting the artist's paintings (Tate) and works on paper (British Museum) for the first time; and Tate Liverpool—the first of the gallery’s major expansions beyond its Millbank home, setting a trend for decentralisation and the sharing of collections which is now accepted practice in the museum world. Both new galleries were commissioned from the brilliant but controversial architect James Stirling. Bowness also laid the foundations for Tate St Ives, which opened after his retirement. Having married, in 1957, Sarah Hepworth-Nicholson, daughter of Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, he became the principal executor of Barbara Hepworth’s estate on her death in 1975. In 1980 he arranged the gift of 26 of her sculptures to the Tate. These works remained in situ in the artist’s studio and garden at St Ives, becoming the first of the Tate’s outstations.

I am attracted to pictures that might be called difficult, which have secrets that are only slowly revealed. There is a puritan streak in me too that I recognise. I like my colour subdued, often monochrome, the artistic gestures restricted and the eroticism present but hidden.Alan Bowness

Bowness’s record on acquisitions was equally impressive. Responding to a revival of interest in figurative painting, he purchased the following outstanding works soon after taking up his appointment: Francis Bacon’s Triptych, August 1972 (1972), one of the tragic “black paintings” in which the artist mourns the recent suicide of his lover, George Dyer, in a hotel bathroom in Paris; David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash (1967), arguably the artist’s most famous painting; Andy Warhol’s sensational Marilyn Diptych (1962); Jean Dubuffet’s witty, graffiti-like Monsieur Plume with Creases in his Trousers (1947); and Max Beckmann’s spellbinding Carnival (1920). The latter signalled that the Tate was at last taking German art seriously, after years of indifference. One first-rate example of figurative painting, however, eluded Bowness’s grasp. He could not persuade his trustees, who included two abstract artists, to commit £200,000 to Lucian Freud’s Large Interior W11 (after Watteau) (1981-83), a group portrait of members of the painter’s extended family. Fifteen years later it sold for over £3.5 million at auction in New York.

Non-representational art was not neglected. Bowness strengthened the Tate’s holdings of American abstraction, buying paintings by Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, and Jasper Johns. He was an early supporter of the young generation of British sculptors who emerged in the 1980s such as Tony Cragg, Richard Deacon and Antony Gormley. He also added important works by Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Max Ernst, René Magritte and Salvador Dalí to the Dada and Surrealist collection. The accession of Picasso’s iconic Weeping Woman (1937) from the Roland Penrose estate—a complicated acquisition with multiple sources of funding—seems in retrospect the apogee of Bowness’s Tate career, coming as it did shortly before his retirement. As far as historic British painting is concerned, I would single out two acquisitions that I remember at the time struck me as unforgettable: Marcus Gheeraerts’s over life-size Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee (1594), naked from the waist down, and Constable’s magnificent The Opening of Waterloo Bridge (exhibited 1832). Bowness preferred monographic exhibitions—Stubbs, Landseer, de Chirico, Sutherland, Bacon—but succeeded in charming Douglas Cooper, the notoriously prickly collector of Cubism, into selecting (with Gary Tinterow) an exhibition about this pivotal moment in art history which was full of masterpieces—the first show of its kind in London.

On his retirement aged 60—as was then the rule—Bowness became director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He was an obvious choice, having taken over the multi-volume catalogue raisonné of Moore’s sculpture from David Sylvester in the 1960s, resulting in a close friendship with Henry and Irina Moore. He established the Henry Moore Institute for the Study of Sculpture in Leeds and kick-started the foundation’s grants programme which to date has disbursed nearly £30m to arts organisations worldwide. More recently, together with his daughter Sophie Bowness, he was the moving spirit behind The Hepworth Wakefield, designed by David Chipperfield, which opened in the city of the sculptor’s birth in 2011 and includes a comprehensive collection of her plasters, tools and archival material donated by the family.

Alan Bowness at his farewell party, Clore Gallery, Tate Gallery (Tate Britain), July 1988, with a faux Henry Moore maquette mocked up with Bowness's head in place of the male figure's. Bowness took over as head of the Henry Moore Foundation and editor of the artist's catalogue raisonné in the same year Tate Gallery photographers

I worked for Alan for seven of his eight years at the Tate, leaving a year before he retired. I remember him above all as a genial presence, someone who seemed at ease with himself. In spite of his modesty, which at times bordered on diffidence, there was a quiet but strong sense of purpose. He was good at giving responsibility to his junior staff. He entrusted me with some high-profile exhibitions, such as Jean Tinguely (1982) and Oskar Kokoschka 1886-1980 (1986), and encouraged me to research and propose acquisitions of contemporary German and Austrian artists—for example, Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer and Arnulf Rainer.

Alan always took great trouble over his appearance, wearing stylish suits with waisted jackets that accentuated his slim figure, wide ties in pastel shades, and highly polished shoes. He had a sweet tooth and could sometimes be glimpsed enjoying puddings in the Tate restaurant, but this never seemed to make any impact on his shape.richard calvocoressi

Alan always took great trouble over his appearance, wearing stylish suits with waisted jackets that accentuated his slim figure, wide ties in pastel shades, and highly polished shoes. He had a sweet tooth and could sometimes be glimpsed enjoying puddings in the Tate restaurant, but this never seemed to make any impact on his shape. His luxuriant hair was a marvel to behold, especially when it turned snow-white. In the audience at the Wigmore Hall, in London, which he frequented into his nineties, he was not difficult to spot.

In 2016 the new Heong Gallery at Downing College, Bowness’s alma mater, opened with an exhibition of art from his personal collection, which he has bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Its character is best summarised as landscape-inspired abstract painting by British artists of the 1950s and 1960s, many of them his friends of the St Ives school. In the catalogue, this least extrovert of human beings confessed:

“I am attracted to pictures that might be called difficult, which have secrets that are only slowly revealed. There is a puritan streak in me too that I recognise. I like my colour subdued, often monochrome, the artistic gestures restricted and the eroticism present but hidden.”

My wife and I have an enduring memory of Alan: trying to keep up with him on an energetic guided tour of St Ives when he was in his seventies, finishing up with Cornish pasties on the balcony of his and Sarah’s flat, with its vast window overlooking Porthmeor Beach. His boyish delight in sharing this spectacular view was as palpable as the pleasure he took in showing us his pictures.

- Alan Bowness, born London 11 January 1928; CBE 1976, knighted 1988; married 1957 Sarah Hepworth-Nicholson (one son, one daughter); died 1 March 2021

- To read a further tribute to Alan Bowness