The first public exhibition the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York ever held, in November 1929, focused on just four artists: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh. The museum returns to those artistic roots this spring with the show Cézanne Drawing (6 June-25 September), the first in the US to bring together the artist’s varied works on paper, from the sketchbooks he kept throughout his career to the large-scale, richly layered watercolours he made.

“Cezanne’s work was essential to the very opening, and the thinking about what the museum would be,” says Jodi Hauptman, MoMA’s senior curator, who co-organised the show with associate curator Samantha Friedman, and curatorial assistant Kiko Aebi. The cornerstone of MoMA’s permanent collection was built by one of the founders of the museum, Lillie P. Bliss—and Cézanne was central to her collection, Hauptman adds. “Cezanne’s The Bather, which for so many years was the first painting you see when you entered the collection on the fifth floor, became synonymous with MoMA,” Friedman says. “And yet, one of the things that we realised, which was really surprising to us when we went back through the exhibition history, is actually how few times there have been monographic treatments” of the artist’s work, she adds.

The forthcoming exhibition aims to correct that with a deeper examination into Cézanne’s work on paper, a medium that was not just a preparatory step on the way to a finished painting, the curators say, but a way for him to experiment with colour, line and visual depth. “For someone who might be more well known to our visitors as a painter, we try to flip the emphasis and look closely at the drawings, to make a strong case that where the artist is perhaps most modern and most experimental, is really on paper,” Hauptman says.

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Cut Watermelon (Nature morte avec pastèque entamée) (1900), pencil and watercolor on paper, 12 3/8in × 19 1/8in Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel. Beyeler Collection. Photo: Peter Schibli

Drawing was a daily habit for Cézanne, resulting in more than 2,100 works on paper over his 50-year-career. MoMA will have more than 200 examples on view, drawn from its own collection as well as loans from public and private collections in the US and internationally. Among them will be at least one watercolour from that inaugural MoMA exhibition—a still-life—as well as works that came to the museum later from Bliss’s collection and from former MoMA president David Rockefeller.

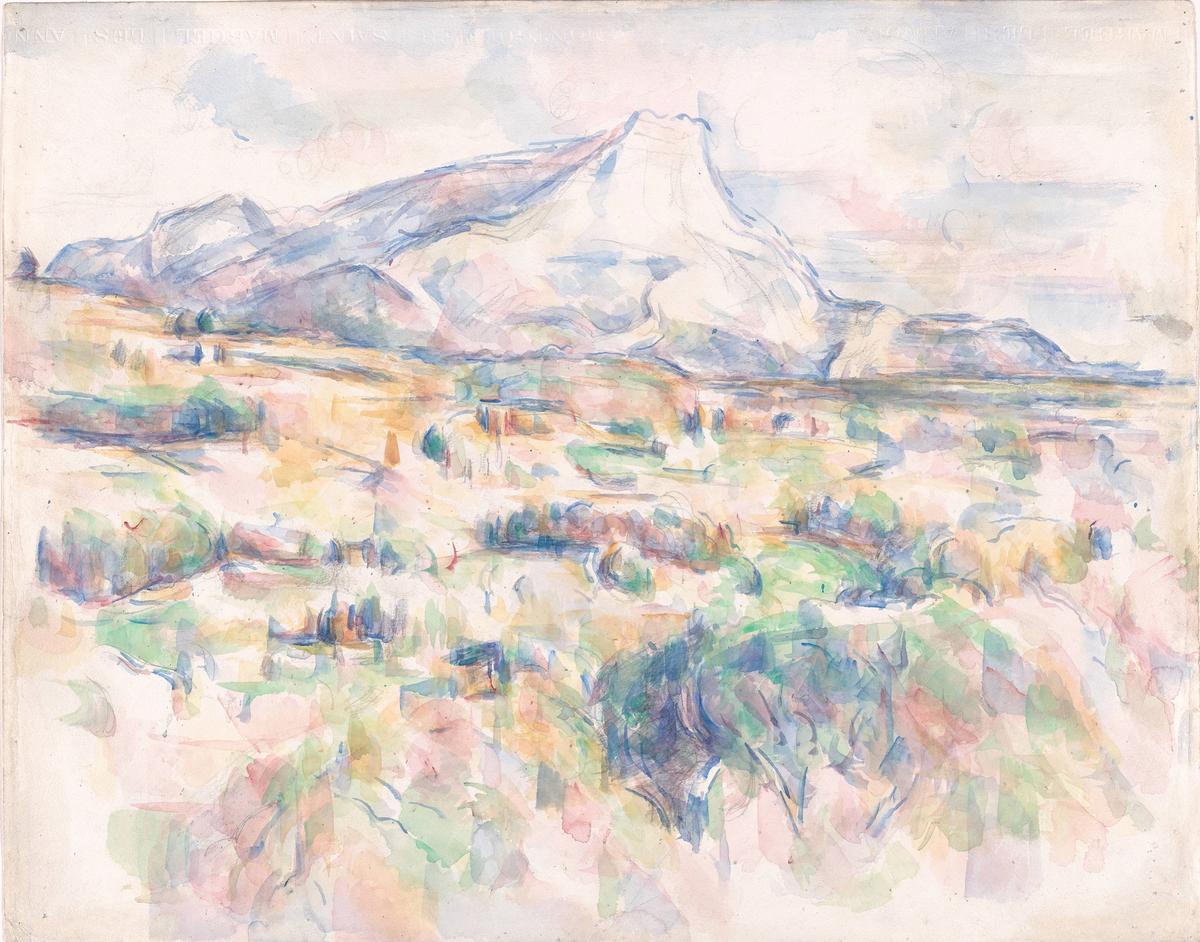

One of the “knockout” experiences for visitors will be getting to see so many of Cezanne’s watercolours together, Hauptman adds. “You don't get the chance to see watercolour so often, because those works are light sensitive. And so, this gathering of watercolours from all over the world by Cézanne is really going to be an amazing visual.” The artist’s delicate handling of the medium was something that was remarked on during his time, and still shines through the works today. “One of Cézanne's contemporaries, who writes about the watercolors, describes the layers in these works as screens, because he recognises the way light passes through,” Hauptman says. “When you really look closely, you can see a red or rose colour on top of a blue on top of a green. And to have each of those patches or ‘screens’ have its own integrity, you have to let them dry because otherwise they would just mix together. There's something about the way Cézanne keeps each colour [separate], it's really kind of remarkable when you see it, you get these beautiful veils of colour.”

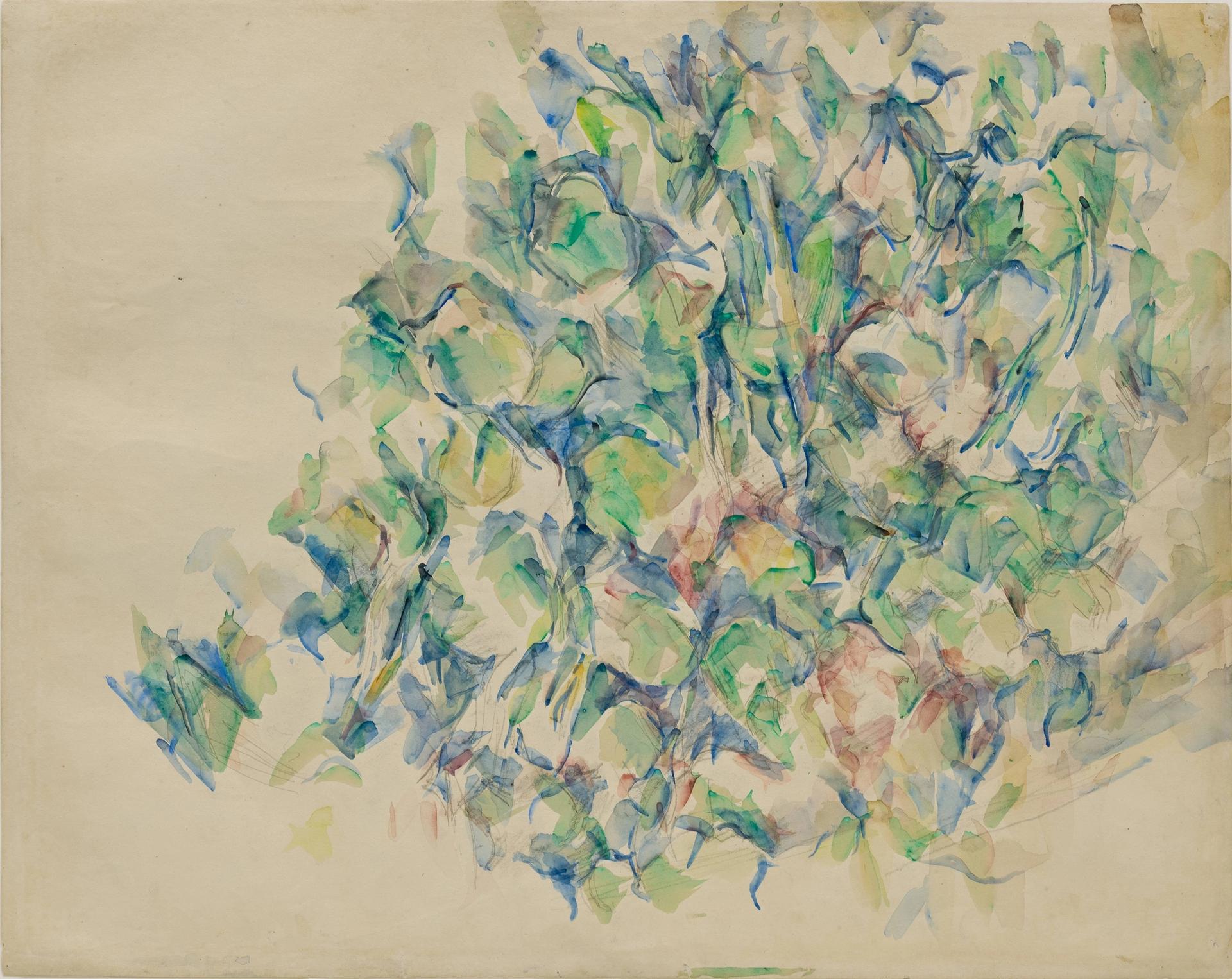

Paul Cézanne, Foliage (Étude de feuillage) (1900–04), watercolor and pencil on wove paper, 17 5/8in × 22 3/8in The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lillie P. Bliss Collection. Photo © MoMA, NY

This level of detailed looking was done with help from Laura Neufeld, associate conservator at MoMA. “If we were in the lab with Laura, looking for example, at Cézanne’s watercolour Foliage, we learned about the order in which pencil and watercolour are relatively applied,” Friedman explains. “Those kinds of things that you can learn from looking under the microscope that you wouldn't have known otherwise—the way that watercolor pooled and collected to create certain effects, and also a sense of layering and how much time Cézanne had to wait after applying one stroke of watercolor, and then having it dry before another stroke would fit on it in just the way that it does.”

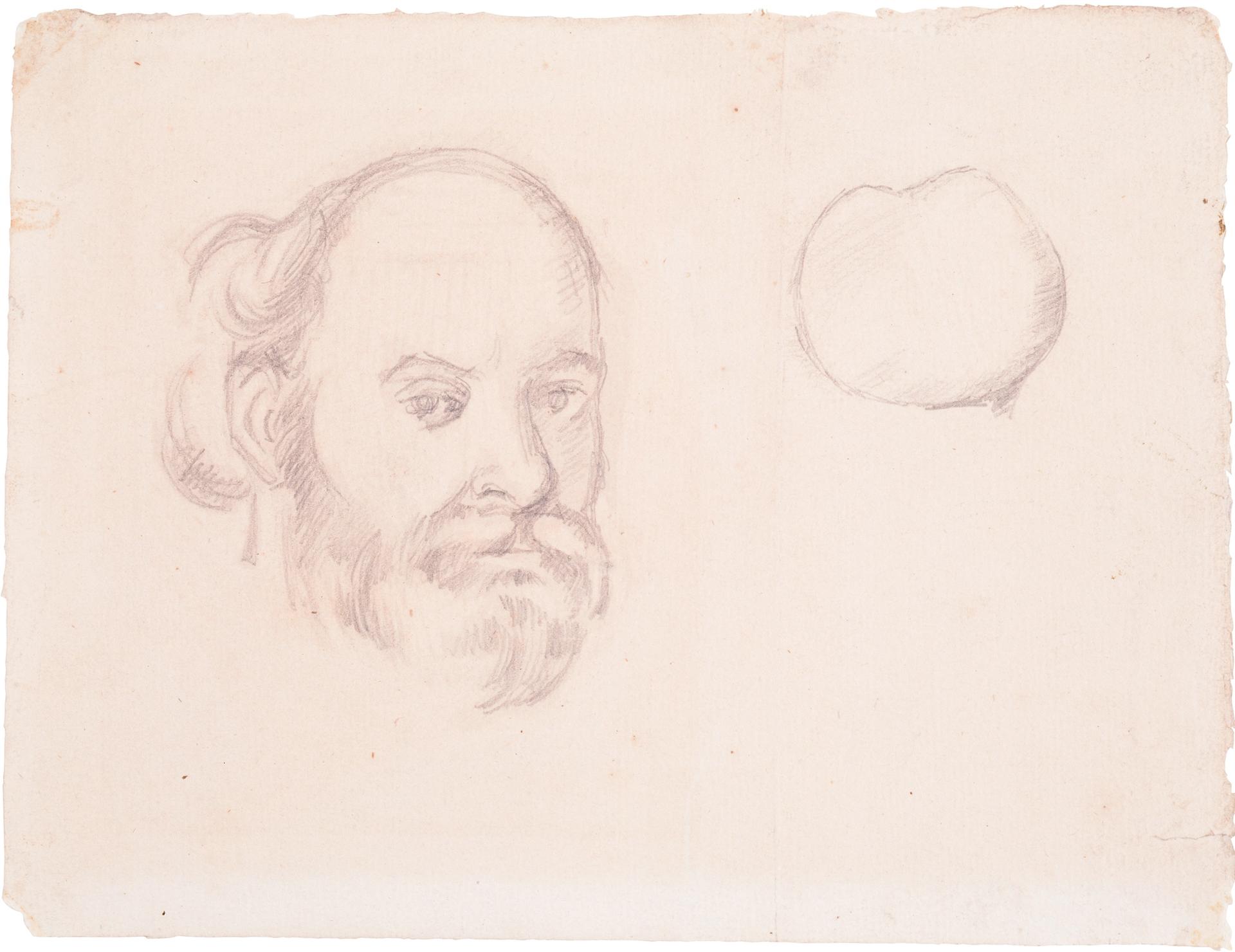

Sheets from Cezanne’s sketchbooks will also be on display, as well as an unbound book owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art that will be displayed in its entirely on the walls, “to give the visitors a sense of what it feels like to immerse in an artist’s sketchbook”, Hauptman says. “We wanted people to have a real sense of the materiality.” Friedman adds: “Aside from the immediate thrill of seeing an artist's sketchbook, and the intimacy that that implies, one of the key goals for us in terms of imparting Cezanne's practice on paper is this sense of iteration that occurs across pages and the relationships between forms on a single sheet—sometimes on two sides of a sheet, sometimes across the spread of a sketchbook, sometimes throughout the pages of the sketchbook. So, really drawing out those relationships rather than thinking of the images as isolated, understanding that these motifs play freely across the body of work, across time, across genres. You see them persist in a way that is part of what makes his drawing practice so modern.”

“Sometimes it'd be even with some humour between two sheets,” Friedman says, “where there's a relationship between the shape of an apple and the dome of Cezanne’s head.”

Paul Cézanne. Self-Portrait and Apple (Autoportrait et pomme) (1880–84), pencil on paper, 6 13/16in × 9 1/16in Cincinnati Art Museum. Gift of Miss Emily Poole. Bridgeman Images

And while the focus of the show will be on Cézanne’s drawings, some key paintings will be included. “We chose paintings very carefully when they were going to tell us something, help us understand the drawing practice more,” Hauptman says. Cézanne’s large painting The Bather, for example, will have a group of related drawings around it, including a sketch for the work from the Morgan Library.

Another group of works centres on one of Cézanne’s favourite subjects, his gardener Vallier. Seeing versions of this figure in both watercolour and oil paint, “You'll see that there's a commonality about the way Cézanne uses unpainted areas of either canvas or paper as a way to create,” Hauptman says. “You can do as much with not painting as painting, or do as much with the blank paper as you do with drawing a mark.” And in particular seeing a personal figure such as Vallier treated in both mediums allows viewers to better appreciate Cézanne’s drawings. “The oil paint on canvas has a kind of thickness, and then the watercolor has these layers of colour,” Hauptman says. “The sitter becomes almost dynamic, there is so much shimmering because of the watercolour, whereas in the painting, there’s a solidity there.”