The dealer Richard Feigen prized connoisseurship. He urged his clients and anyone else who would listen (including the press) to buy the finest works of art that they could afford. “Shit never costs that much less,” he counselled.

“He also said that you’ll never regret how much money you spent for something; you’ll only regret how much you didn’t spend if you really wanted it,” says Laurence Kanter, chief curator of the Yale University Art Gallery, who exhibited works from Feigen’s own collection in 2010. Feigen’s advice echoed that of the dealer Joseph Duveen, infused with Feigen’s own version of a foul-mouthed plain-spoken Harry Truman, in the raspy Chicago accent that he never lost despite more than six decades in New York. He railed against the auction houses, the inflation of prices and reputations, the industrial expansion of the art market, and the threat to his calling as a “collector in dealer’s clothes”. His gallery still did plenty of business, and Feigen assembled an enviable personal collection.

“I don’t think there’s anything that we didn’t sell,” says Feigen’s long-time former gallery president Frances Beatty, who brought the gallery such major buyers as Alfred Taubman and Donald Bren. Clients ranged from the financier Saul Steinberg to Steve Wynn to Leon Black and, as Beatty notes, “125 museums”. The dealer’s personal taste was a mixed bag—Turner and Constable, plus the Chicagoan Ivan Albright and the reclusive Ray Johnson, whose estate the gallery (and now Beatty) represents. There was also the dreamy constructor of collages and boxes Joseph Cornell, and the German refugee Max Beckmann. Orazio Gentileschi was a favourite, as were 15th-century gold ground paintings.

The son of a lawyer, Feigen was born in Chicago in 1930 and studied art history and English at Yale and business at Harvard. He opened his first gallery in Chicago in 1957, but soon outgrew his hometown. It was an antisemitic place in his youth, he recalled in his caustic 2000 memoir, Tales from the Art Crypt: the Painters, the Museums, the Curators, the Collectors, the Auctions, the Art. And, he lamented, property speculators were already demolishing some of the city’s architectural treasures.

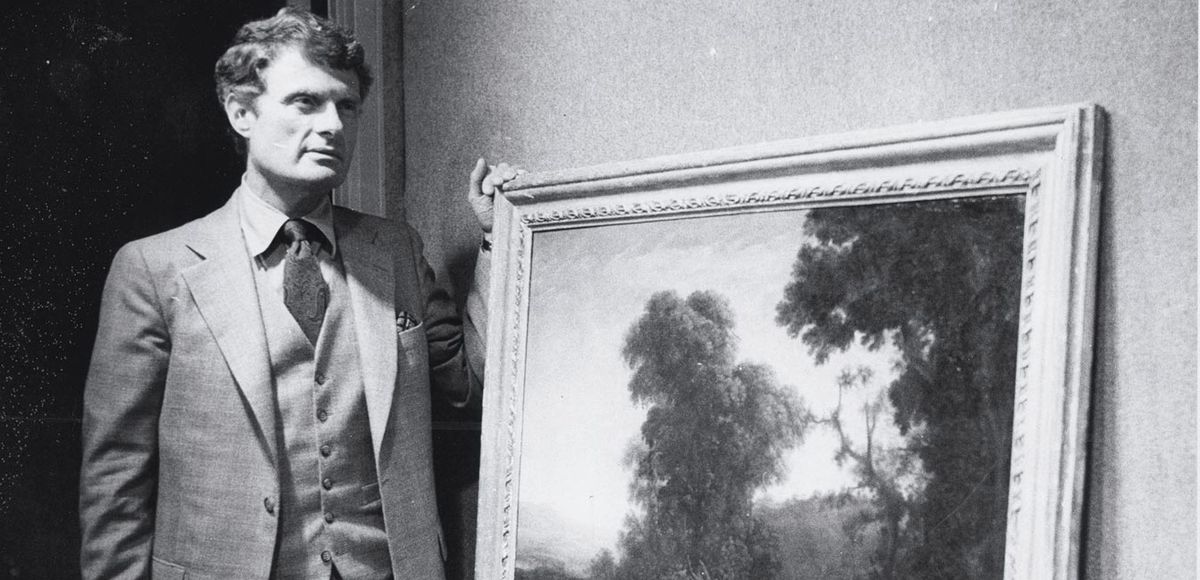

In New York, starting near Madison Avenue, he joined with Leo Castelli in 1965 in SoHo, then a warren of small industry, returning uptown to commission a building by the architect Hans Hollein (father of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s director, Max Hollein) on East 79th Street. His galleries sold contemporary art and Impressionism. Feigen’s politics, always liberal, were lampooned by Tom Wolfe in his New York magazine article “Radical Chic” (1970). The portrait, a dig at earnest glitterati, missed the handsome dealer’s signature wryness. Like Castelli, Feigen was rarely seen in New York without a necktie.

Feigen opened galleries in Los Angeles and London, plus a contemporary gallery that moved from Chicago to Chelsea in New York in 1998. The younger Old Master dealer Robert Simon recalls that, when he was a student in London, the acerbic Feigen was the first art dealer he met. Simon says the meeting swore him off becoming an art dealer—for a while. Years later the two dealers found they had similar interests and overlapping taste. Simon described Feigen as “someone who’s not afraid of an ugly picture, a difficult picture”, whether by Albright or Beckmann.

Feigen’s politics, liberal throughout his life, were lampooned by Tom Wolfe in his New York magazine article ‘Radical Chic’ (1970). The portrait, a dig at earnest glitterati, missed the handsome dealer’s signature wryness. Like [Leo] Castelli, Feigen was rarely seen in New York without a necktie.

Friends and others agreed that you did not have to like Richard Feigen to like what he liked. “He was a very canny guy, very sharp, but I don’t know how beloved he was,” Simon says. For George Wachter of Sotheby’s, Feigen was “a guy who understood what wasn’t popular but was important, and went out and found those kinds of artists”.

“Well, I don’t want to be arrogant,” Feigen told an interviewer for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art in 2009. “I have a very good eye. I have very, very good taste,”

Feigen’s taste made him something of an outlier. He had the clients of an insider, despite his opinions, which he expressed loudly, as art world jeremiads. He said the Met didn’t need to show contemporary art as it was in so many other museums. He called the auction houses bullies (and worse), even though Taubman, the chairman of Sotheby’s, bought from him. Museums also bought, but he scolded museum directors for following the crowd rather than leading it. In a comment piece for The Art Newspaper in 2007, Feigen sounded apocalyptic about a “bubble” of cash in the market: “The auction houses won’t care because they have no ongoing responsibility to their clients, and there will be an endless supply of ... the newly trendy, that they can help promote to feed these insatiable monsters.”

Sometimes those opinions made a difference. In 1990, the Barnes Foundation, in Pennsylvania, announced that it planned to sell paintings in violation of the wishes of its founder Dr Albert C. Barnes in order to establish a patronage fund at Lincoln University—which controlled the Barnes board. Feigen led a group of the museum's advisory board in opposition to that threatened sale. “That the collection remains intact today is very much a result of his timely efforts,” said Nick Tinari, a former student at the Barnes.

Feigen with the dealer Puppa Sayn-Wittgenstein Nottebohm, who teamed up with Richard L. Feigen & Co in 2018 Courtesy of Richard L. Feigen & Co

Feigen found few allies in the broader art world to preserve the foundation as Barnes intended it. In the 2009 documentary film The Art of the Steal, Feigen walked through galleries at Sotheby’s, where lesser works by artists collected by Barnes were on view. He mocked efforts to monetise some of the Barnes Foundation’s best-known works. “Cézanne’s Card Players would probably be beyond any individual’s capacity—how much money is in any one place? The Getty couldn’t afford it. You’d need some sort of a nation to buy it,” he said on camera.

In 2000, Feigen acquired a painting said to be by Ludovico Carracci from Lempertz auction house in Cologne. The picture had come from a 1937 sale in Dusseldorf from Galerie Stern, a Jewish-owned business forced by the Nazi government to sell its inventory at heavily reduced prices. The proprietor, Max Stern, fled to England and later established a gallery in Montreal. The Max Stern Art Restitution Project tracks and seeks to recover works from the 1937 sale. Feigen surrendered the painting to the US authorities when he learned the 1937 sale under duress was illegal. Facing a tough battle for compensation in a German court, he said, “They [Lempertz] may not have to abide by American law, but they may have to abide by American publicity…” He sued Lempertz in Germany to get his money back, losing at trial and on appeal.

By 2015, Feigen was slowing down after a stroke. In 2016, Orazio Gentileschi’s Danaë, which he treasured, was sold at Sotheby’s to the Getty for $30.5m. In 2019, he consigned another ten paintings at Christie’s. “I hope none of them will sell, because I want them back in my living room,” he joked.

Also in that year, Feigen donated Carlo Saraceni’s altarpiece The Dormition of the Virgin (around 1612) to the Metropolitan Museum, in honour of Max Hollein and the Met’s 150th anniversary. Feigen gave the Yale University Art Gallery works by Guercino and Scarsellino within the past year, adding to pictures by Abraham Janssens, Annibale Carracci and Paolo Uccello he had donated in the previous decade.

For all Feigen’s disparaging of auction houses and museums, they did, after all, share a destiny.

He is survived by his widow, Isabelle Harnoncourt Feigen. His two previous marriages—to Sandra Elizabeth Canning in 1966 and Margaret Culver in 1998—ended in divorce.

Two children from his first marriage survive him, Philippa Feigen Malkin and Richard Wood Bliss Feigen, as do three step children, Stephanie Harnoncourt Wisowaty, Alexander Richard Wisowaty and Leonie Harnoncourt Wisowaty, and three grandchildren. His sister, who also survives him, is the Los Angeles-based feminist lawyer Brenda Feigen.

Richard Lee Feigen, born Chicago 8 August 1930, died Mount Kisco, New York State 29 January 2021.

- "The ultimate dealer of Old Master paintings and an excellent connoisseur of art ".

.