Camille Pissarro met Vincent van Gogh while the Dutchman was living in Paris in 1887 with his brother Theo. Pissarro is said to have predicted that Van Gogh would “either go mad or leave the Impressionists far behind”. A few years later he added: “That he would do both, I did not foresee.”

The origins of this little-known quote are obscure, but it was reported by the German critic Max Osborn, who started writing on both Pissarro and Van Gogh in the very early 1900s. He recorded Pissarro’s comment in his 1945 book Der Bunte Spiegel (The Colourful Mirror).

What has not been appreciated is that Pissarro’s admiration led him to acquire Van Gogh’s Portrait of Père Tanguy (1887), which is now in the collection of the Ny Carlsburg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, the museum established by the brewing family. Pissarro’s ownership is not recorded in the Van Gogh literature, nor in the Glyptotek’s provenance records—but it is revealed in an unpublished document at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

The Portrait of Père Tanguy originally belonged to the sitter of the painting, a paintseller who died in 1894. In 1901 the picture was lent to a Paris exhibition by the dealer Ambroise Vollard. Pissarro probably acquired the Van Gogh at that time, perhaps in an exchange with Vollard.

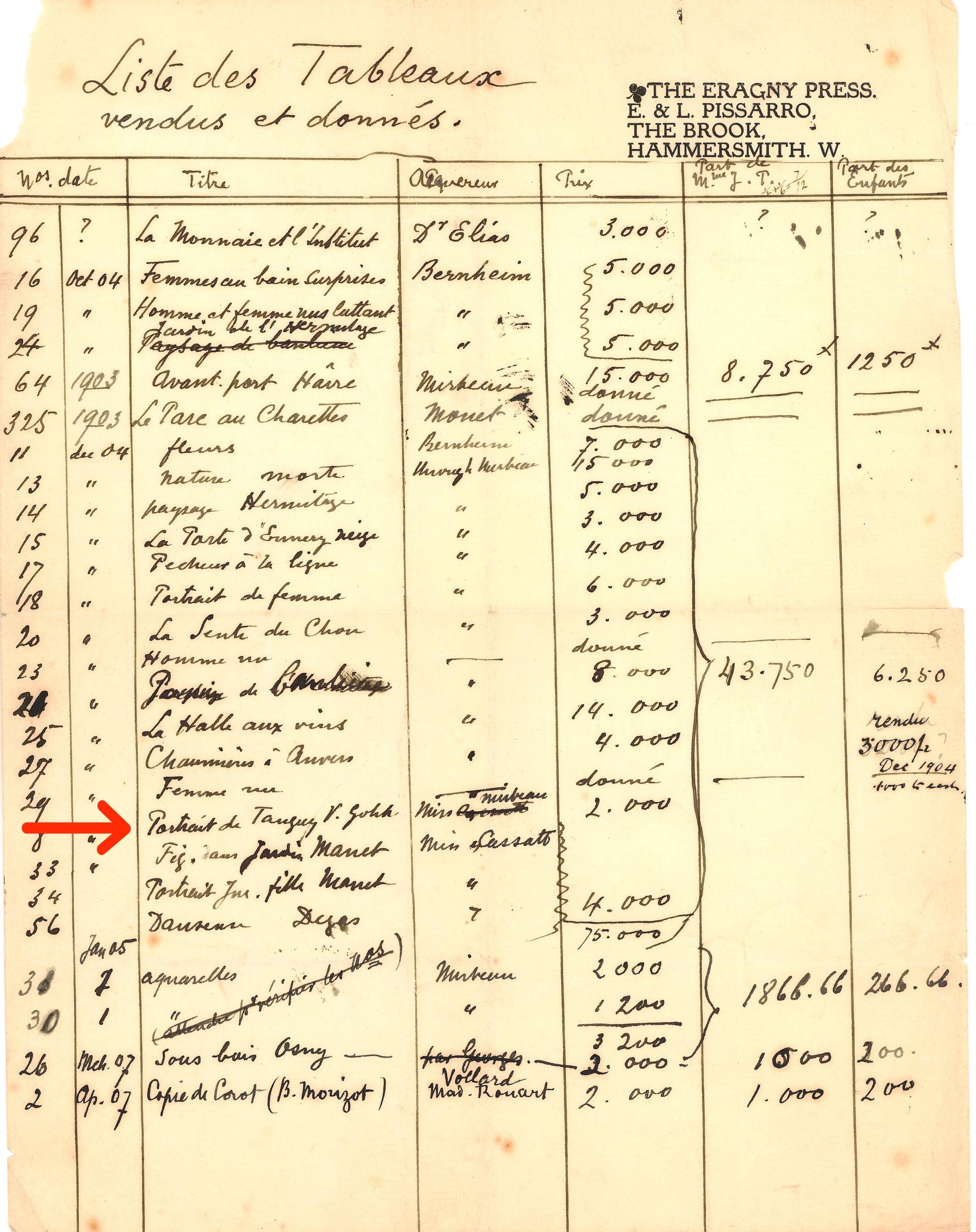

Pissarro’s ownership is recorded in an unpublished inventory compiled shortly after his death in 1903 by his son Lucien, who was then living in Hammersmith, in west London. This document, which has escaped attention, is in the Ashmolean collection, as part of the Pissarro archive given by the family.

Lucien Pissarro’s inventory of his father’s paintings, 1903-07 (with the Van Gogh indicated in red) Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In the list of paintings compiled in 1903-07, the document records “Portrait de Tanguy, V. Gohh” (the last two letters are slightly unclear, but the French always found it difficult spell the name). Valued at 2,000 francs, the name “Miss Cassatt” (the American Impressionist artist Mary Cassatt) is crossed out and replaced by “Mirbeau”. Octave Mirbeau was an important Parisian art critic. The 1904 sale is also confirmed by a separate family note (in a private collection) written by another of Camille’s sons, Rodo.

Colin Harrison, an Ashmolean curator, is now helping to organise a Pissarro exhibition that will open at the Kunstmuseum Basel (4 September 2021-23 January 2022) and then move to Oxford (February-June 2022). His independent research for the show also “confirms the discovery that Camille owned the portrait which is now at the Glyptotek”.

Camille Pissarro’s Self-Portrait (1903) Courtesy of the Tate, London

Octave Mirbeau held onto the Portrait of Père Tanguy until 1919. It was bought by the Copenhagen collector Wilhelm Hansen and later acquired for the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum.

The 1887 portrait by Van Gogh depicts Père (Father, a respectful term for an elderly man) Julien Tanguy, a political and artistic radical who sold artists’ supplies in Paris. Both Pissarro and Van Gogh patronised his shop. In Vincent’s portrait, Tanguy is dressed in the apron that he wore at work. His surname can just be made out in the upper-left corner and Vincent’s signature in the lower left. The picture is painted in the earthy colours of Van Gogh’s Dutch and early French years.

Van Gogh painted two other portraits of Père Tanguy—one acquired by the sculptor Auguste Rodin (now at the Musée Rodin in Paris) and the other has been with the family of the Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos.

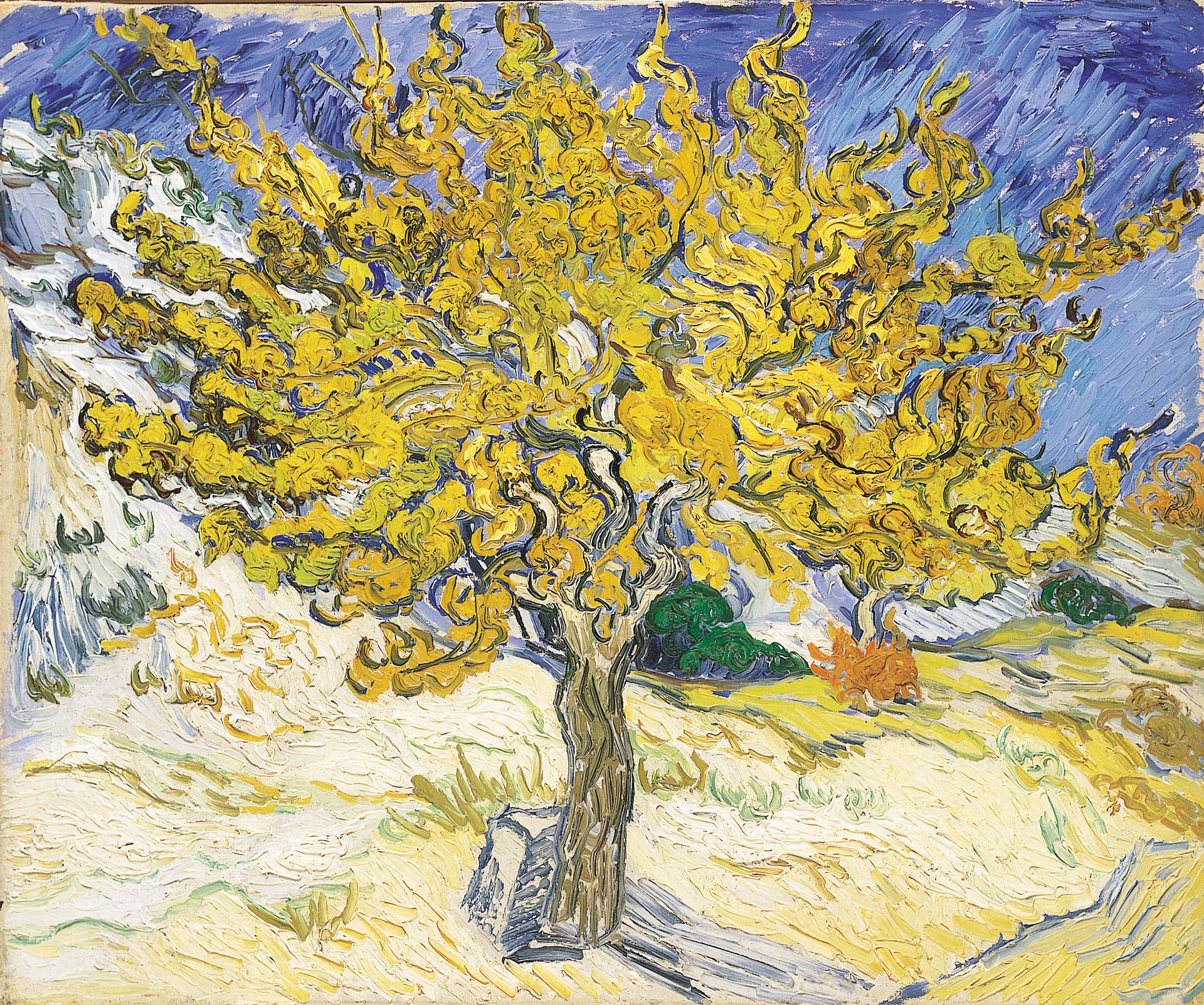

Pissarro also owned a second Van Gogh, The Mulberry Tree (1889), now owned by the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Mulberry Tree (October 1889) Courtesy of the Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena, Gift of Mr. Norton Simon

Although Pissarro was quite correct in predicting that he and his colleagues would be overtaken by Van Gogh, attitudes towards mental disorders have changed considerably—we would no longer describe him as “mad”. And to put another myth to rest: Van Gogh did not paint as a madman, he successfully worked despite his medical problems.

In the portrait of Père Tanguy once owned by Pissaro, Van Gogh lovingly captures the features of the paintseller who did so much to support the Impressionists and their followers.