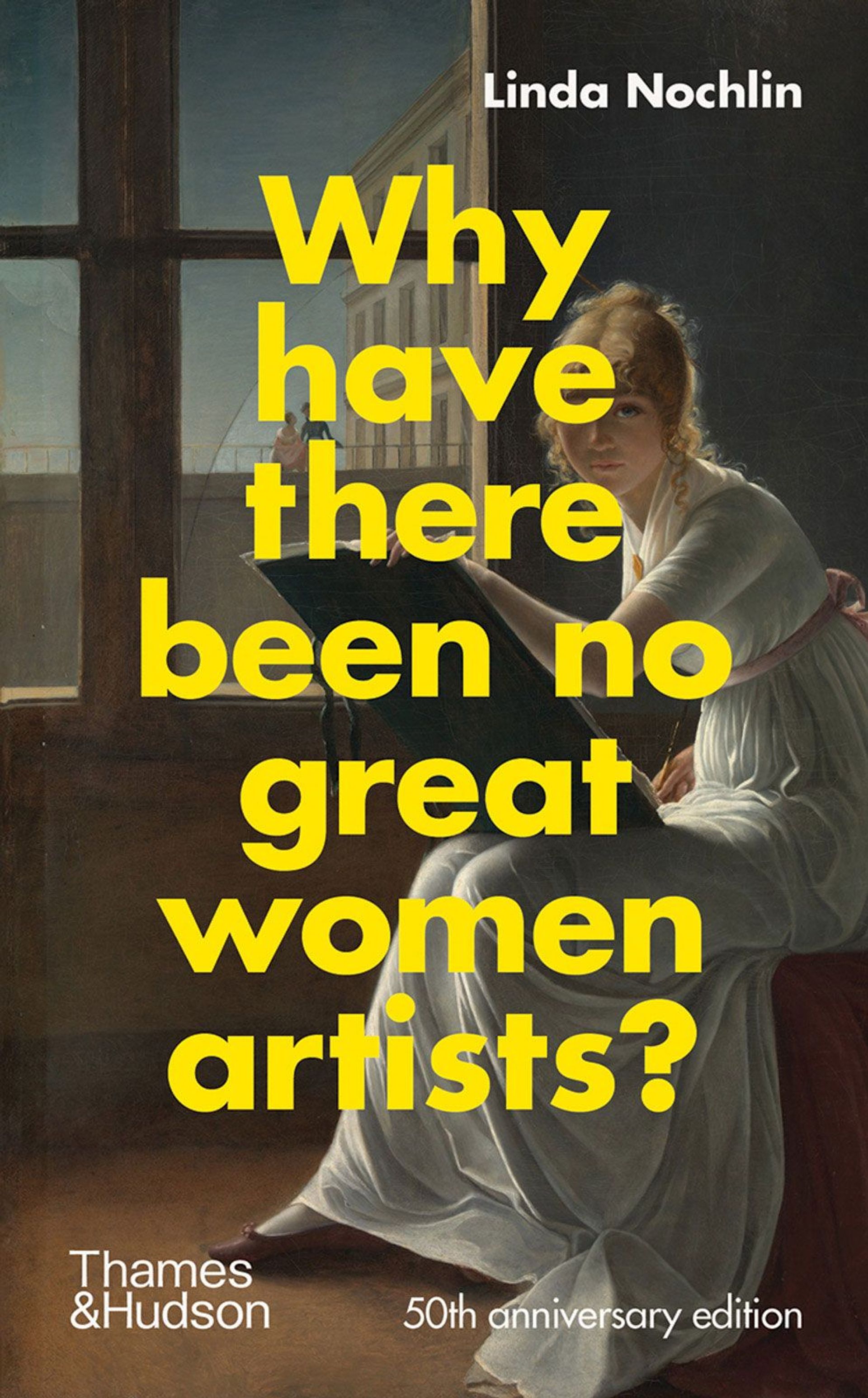

“Why have there been no great women artists?” It is a silly question, really, and the art historian Linda Nochlin (1931-2017) certainly thought so when a male gallerist put it to her. She responded with a passionate and provocative essay published in 1971 as part of a controversial issue on “Women’s Liberation, Women Artists and Art History” in the journal ARTnews. The essay was preceded by the strapline: “Implications of the Women’s Lib movement for art history and for the contemporary art scene—or, silly questions deserve long answers.” In roughly 4,000 words, Nochlin dismantled the question to reveal the assumptions that lie behind it, as well as the answer it surreptitiously supplies: “There are no great women artists because women are incapable of greatness.”

To celebrate the essay’s 50th anniversary this year, Thames & Hudson is publishing Nochlin’s rallying cry alongside its reappraisal, “Thirty Years After”, in a standalone edition. There is a pithy introduction by Catherine Grant, a senior lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, and more than a dozen illustrations—including a reproduction of Marie Denise Villers’s Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes (1801) on the cover. With bright, bold text pasted over a centuries-old painting, it recalls contemporary fiction such as Amina Cain’s Indelicacy and Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation. But do the words within still make for stimulating reading?

Linda Nochlin © Adam Husted 2006, All Rights Reserved

Conceived during the heady beginnings of the biggest feminist movement since women’s suffrage, the 1971 article helped to shatter the illusion that art history is universal and, in doing so, changed the field forever. Nochlin did for the history of art what Virginia Woolf did for literary studies in “A Room of One’s Own”. Nochlin’s essay explored how women artists were hobbled by institutional strictures and social prejudices: “The fault lies not in the stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education—education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals.”

With her characteristic wit, Nochlin demanded a revision of art history’s crumbling methods and male-ordered narratives. She discredited the “golden-nugget theory of genius”, the myth that male artists contained within them innate creativity, and called for a more socially engaged consideration of the conditions for producing art. She pointed to life drawing, a foundational skill for artists from the Renaissance to the 19th century, from which women were excluded. “To be deprived of this ultimate stage of training meant, in effect, to be deprived of the possibility of creating major art works.” She writes not only of gender bias, but also of race and class.

Her tone is conversational, her point profound: the art world was, and is, tangled up with politics and power. Of course, a band of women did achieve artistic excellence, despite the tremendous odds against them. Nochlin mentions Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Rosa Bonheur, as well as Artemisia Gentileschi, whose Judith Beheading Holofernes (around 1613-14) featured alongside the title page of the essay in ARTnews. A caption suggested the bloody painting could be “[a] banner for Women’s Lib”.

Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Holofernes (around 1613-14) was printed alongside the essay in ARTnews © Gallerie degli Uffizi

Nochlin’s follow-up essay, written three decades later, examined what had changed. Theory had transformed the way academics and critics thought about gender and identity in art, and the work of artists such as Louise Bourgeois had sparked critical discourse by female writers. In the 20th century there was the advent of the “New Woman”—a woman who was at home out of the home—while the 1960s and 1970s saw artists like Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger take an active role in shaping public space.

Over the past decade, public art institutions have begun to redress the widespread gender imbalance in their collections, with 2021 shaping up to be a bumper year for major retrospectives on women artists. There are travelling shows dedicated to Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Georgia O’Keeffe, both of whom Nochlin cites in her 1971 essay, as well as comprehensive exhibitions dedicated to Barbara Kruger, Judy Chicago, Paula Rego and Marina Abramović. And yet, still today, achieving equality is an ongoing project.

The key, as Nochlin states, is critical practice. Rather than simply inserting women into the canon, we must crack open the canon itself. We need to question conventional ways of thinking, writing, seeing, and challenge contradictions. These bold and candid essays—just two of the author’s many contributions to art history—provide readers with the tools to do so. They also encourage mischief. As Nochlin wrote, “feminist art history is there to make trouble, to call into question, to ruffle feathers”.

The 50th anniversary edition of Nochlin’s 1971 essay, which also includes its reappraisal, ‘Thirty Years After’ © Thames & Hudson

• Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? 50th Anniversary Edition, Linda Nochlin, Thames & Hudson, 112pp, £9.99/$14.95 (hb)