The collector Daniel Wolf had three qualities that he always seemed to hold in perfect balance—a love and sensitivity for beautiful objects, a deep appreciation of the wonders of nature, and finally a gift for intense friendship, not necessarily with people in the art world. Indeed, he consciously distanced himself from many art figures that he felt were untrue in their “passions”. He preferred people from the world of film-making, journalism, architecture and those artists in whom he believed and from whom he felt he could learn. Wolf died at his house in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, the first to be commissioned from the Italian designer Ettore Sottsass, who—very much as a result of Wolf’s inspired and enthusiastic commission—turned in the 1980s from a focus on industrial and retail design to the practice of domestic architecture.

Daniel Wolf was close to his father, Erving—a rags-to-riches oil-based entrepreneur. Erving Wolf and his wife, Joyce Mandel, were major collectors of American Art—largely outstanding 19th-century paintings, furniture and decorative arts, but also drawings and furniture by Frank Lloyd Wright. They enriched the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, through gifts and an endowment of a gallery devoted to American painting. Each Saturday morning, until about ten years ago, father and son would get up at 6am and go down with paper cups of coffee to the 25th Street antique—mostly junk—market, and scour, both of them with the sharpest of eyes, for objects that needed rescuing for their collection.

Father and son also had a profound love of the nature of the “Wild West”. This led them to acquire large tracts of land near the small town of Ridgway, in a remote part of southwest Colorado, high up under the shadow of Mount Sneffels. It is home to elk, deer, bear, coyote, bald eagles, and hummingbirds. On the surrounding plains they farmed cattle; Wolf rode with the local cowboys, and for years lived in a simple hut, galloping across the plains and trekking on horseback into the mountains to camp, sometimes pulling rock crystals out of the mountain sides. In 1987-89 the unlikely but spectacular Sottsass house was built, a place to live but also to look into the night skies.

A lover of the Wild West: Wolf on the terrace of his Ettore Sottsass house at Ridgway, Colorado, 1990 © Joel Sternfeld

Wolf at home, in Ridgway, Colorado, 1990 © Joel Sternfeld

But it is as a New York art person that Wolf will be remembered by the larger world. He was not someone who looked for fame, preferring to remain under the radar. If he had celebrity, it was as husband of his much-beloved Maya Lin, the American sculptor, land artist and architect—creator of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, and initiator of the environmental campaign What is Missing?, in which Wolf participated. However, long before, as a young man in his early and mid-20s, Wolf made a huge impact in the world of art through his many-faceted involvements in the history, collection and museology of photography.

Wolf and his wife the sculptor, land artist and architect Maya Lin at home in Colorado in 2019 with their daughters India (far left) and Rachel (second left) Courtesy of Ana Dubson

Wolf was born in 1955, in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and began to discover photography, seriously, as a 13- to 14-year-old schoolboy at Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, even enthusing his class-mates to collect. At this time, he took classes with the famous photographer Minor White, who was himself personally connected with photographers such as Berenice Abbott, Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, linking Wolf to one of the great American art traditions. Minor White also passed to Wolf other interests—ancient Eastern mysticism and his own wonderment of the natural world expressed in the grandeur of the American landscape. Or in the magic of rocks and crystalline quartz, of which—as Andy Warhol did—Wolf accumulated spectacular examples from all over the world. Minor White also introduced Wolf to the world of the I Ching, laying the groundwork for his later enthusiastic involvement with Merce Cunningham and his eponymous dance company. Wolf acted as chairperson for the company, which led to a friendship with the composer John Cage, who often stayed with him in the Colorado mountains.

As a student at the liberal arts college Bennington, in Vermont, Wolf continued searching for photographs and, on graduation in 1976, took a suitcase to the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, setting up a stall from where he sold vintage photos. He was so successful that in 1978, he opened a gallery on West 57th Street that lasted a decade, mounting there 100 carefully curated exhibitions of classic and contemporary photographers—amongst them Gustave LeGray, Minor White, Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, but also John Coplans, Eliot Porter, Sheila Metzner and many others. He used to recall, ruefully, how he had turned down the Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto when he came to his gallery.

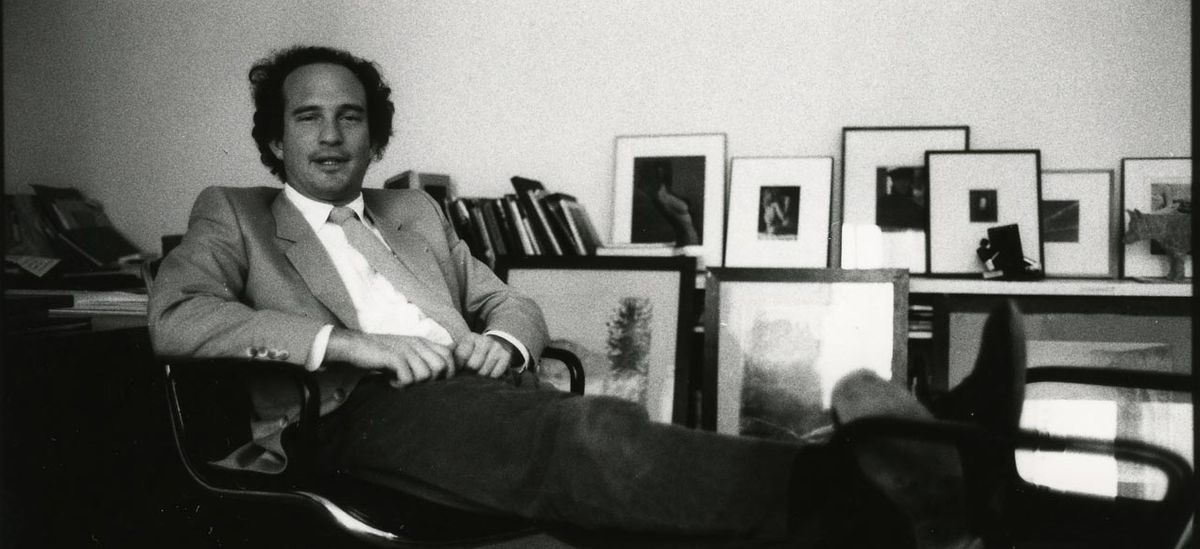

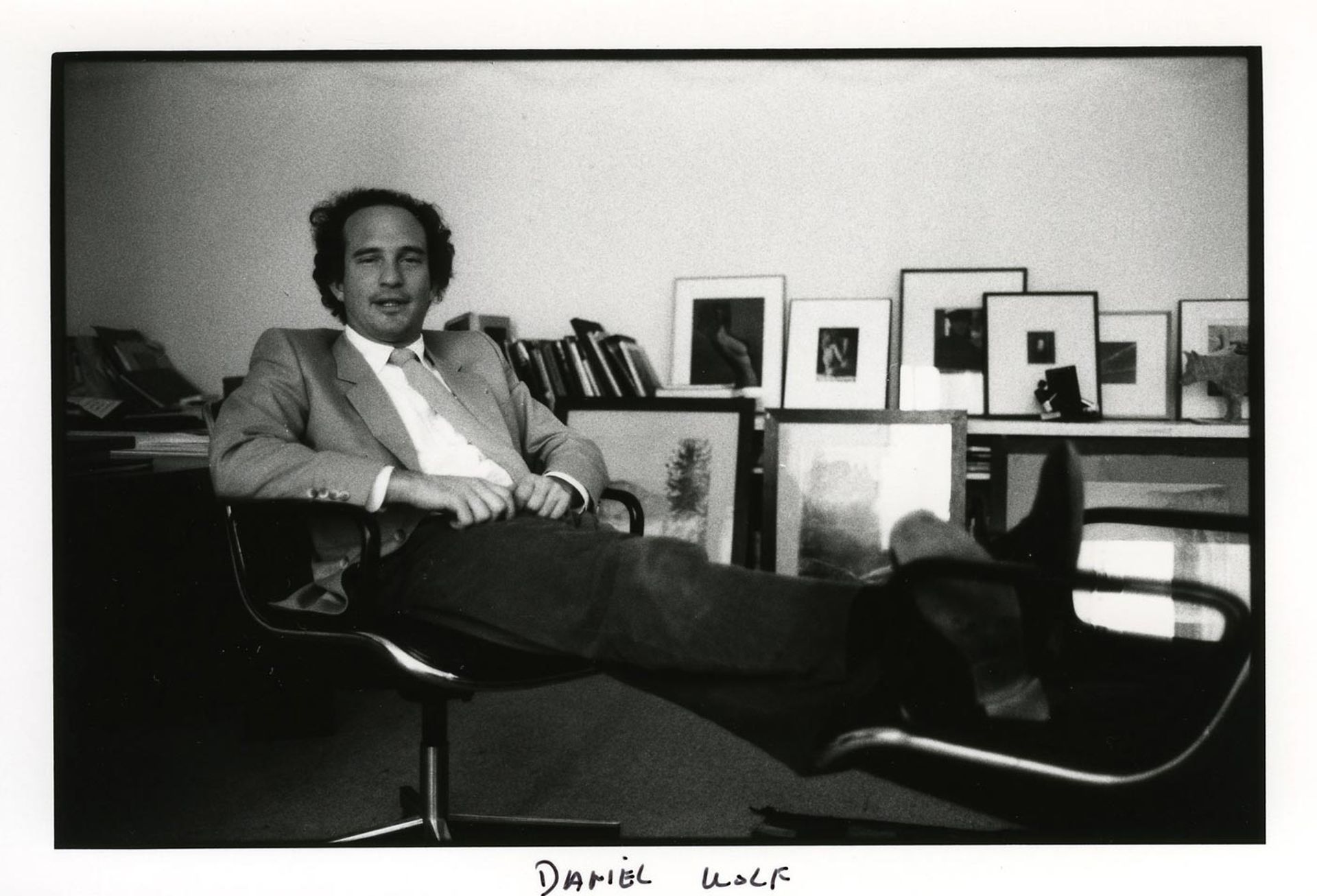

Wolf photographed at his New York gallery by his friend Johnny Pigozzi, 1983 © Johnny Pigozzi

Arguably Wolf’s greatest achievement was to pull together, in secret, from some dozen or more existing collections, a unique museum holding of photography, old and new, for the J. Paul Getty Museum and its director, John Walsh. Photography became one of the most high-profile departments of a museum otherwise devoted to ancient and classical Western art before 1900. Amongst the collectors Wolf dealt with were Sam Wagstaff and the great Parisian dealer/scholar André Jammes. Wagstaff himself sold to Wolf—without at the time knowing his collection’s destiny—more than 25,000 extraordinary images, among them works by his two young protégés, Robert Mapplethorpe and Gerald Incandela, both of whom he introduced to Wolf. The quality of the Getty collection can surely never be equalled. The Getty was the largest lender to The Art of Photography 1839-1989, the 1989 exhibition at The Royal Academy, London, celebrating the 150th anniversary of the invention of photography, with Wolf as lead curator. At the time this was, within the RA, a controversial subject for a show—with many members still doubting that photography was a legitimate art.

Wolf photographed in the aspen woods near his home in Colorado by his daughter India, 2020 Courtesy of India Wolf

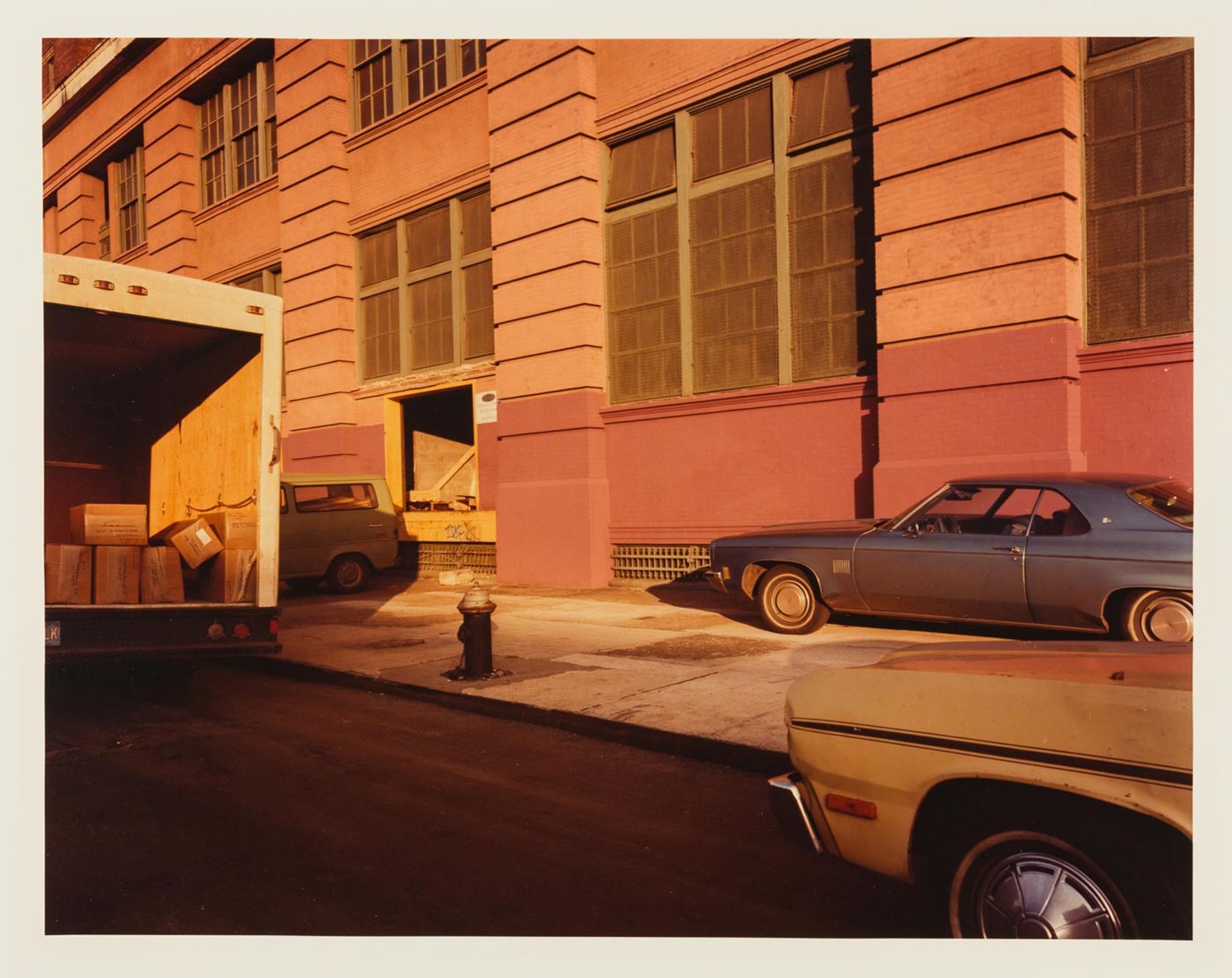

The making of collections of subjects “that can never be equalled” characterised Wolf’s ambition as he looked for new acquisitions—in recent years mostly via the internet, which he came to regard as the most efficient marketplace of our times. Areas in which Wolf collected ranged far and wide, but his romantic love for the United States and its cultures led him to subjects like American Arts and Crafts—including the Californian furniture of the Greene Brothers (known as Greene & Greene), contemporaries of Charles Robert Ashbee and the Viennese Secession. And forever photography—19th-century albums, little known photographers of the 1970s such as the New Yorker Jerry Shore (1935-94), whose work after his death Wolf acquired in its entirety, archiving and studying and having it shown at the Met Museum in 2006, when Shore was hailed by critics like Adam Gopnik of the New Yorker as an Edward Hopper of his time. Aaron Rose—his greatest friend—was another artist/photographer, of architecture, nature and the stars, whose work Wolf was certain will come as another revelation to the world when it is properly revealed.

For Daniel Wolf, collecting beautiful and extraordinary things was the route to self-education, self-knowledge, discovery, wonderment—to pass on and, as he fervently hoped, to be appreciated by a wider world

Going back to the very beginnings of photography, Wolf managed in recent years to find unknown daguerreotypes by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey, whose journeys around the Mediterranean in the 1840s documented, with the eye of a true artist, great monuments of the ancient world, many of them in the meantime destroyed or altered. Part of his collection contributed to the first ever show of Prangey at the Met, now at the Musée D’Orsay.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey, "91. Athènes. 1842. Propylées. Pris de l'Intérieur", daguerreotype, 1842. Wolf's discovery of unknown daguerreotypes by Prangey enabled the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Musée D'Orsay, Paris, to mount one-man shows of the pioneer photographer's work Courtesy of Daniel Wolf Collection

Jerry Shore, Untitled, 1982. Wolf discovered Shore's Hopper-like street photography and acquired his archive Courtesy of Daniel Wolf Collection

Wolf loved some contemporary artists, for example Jeff Koons—but was neither able nor willing to go into that, to him, crazy price-world—and Andy Warhol, the subject of an extraordinary four-hour documentary by Ric Burns, first shown in 2006, which Wolf actively and with enthusiasm co-produced. But he had many doubts about the contemporary art collecting scene, judging it to be largely an arbitrary ruse for the rich to cover their walls with easy-to-recognise-trophies.

For Daniel Wolf, collecting, “touching”, beautiful and extraordinary things was the route to self-education, self-knowledge, discovery, wonderment—to pass on and, as he fervently hoped, to be appreciated by a wider world.

About seven years ago he acquired an abandoned jailhouse on the Hudson River, in Yonkers, just north of Manhattan, which, with the help of Maya Lin, he converted into a space in which all the objects, two- and three-dimensional, that he had brought together over decades and which for the most part had lain in boxes in warehouses, became visibly accessible to him, his friends and museum professionals. There he spent more and more time, secretly making refined abstract oil-stick drawings, something he hoped, too, he might one day be able to share with a wider world.

- Daniel Wolf, born Cheyenne, Wyoming 29 March 1955; married 1996 Maya Lin (two daughters); died Ridgway, Colorado 25 January 2021.