The art historian Leo Steinberg (1920-2011) was known for defying orthodoxy, most memorably in his 1983 book The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, in which he argued that the genitals depicted in images of the infant Jesus and the Passion were crucial to establishing the saviour’s essential humanity. The book ruffled feathers: some found the topic prurient, while others challenged Steinberg’s interpretation of the visual evidence. But most were struck by the incisiveness of his conversational voice, which he had already wielded in essays and criticism about artists including Pablo Picasso and Jasper Johns.

Now, an exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, aims to explore a less acknowledged part of Steinberg’s legacy: his capacious collecting of prints. The show will present nearly 200 prints, drawn from his collection of around 3,500 that were acquired by the Blanton in 2002, attesting to how prints inspired and informed Steinberg’s scholarship and critical writing.

“Because Steinberg first trained as an artist, he had the confidence to approach how artists face that blank piece of paper,” says the show’s curator Holly Borham. “He was looking at what artists did over the centuries” with the medium.

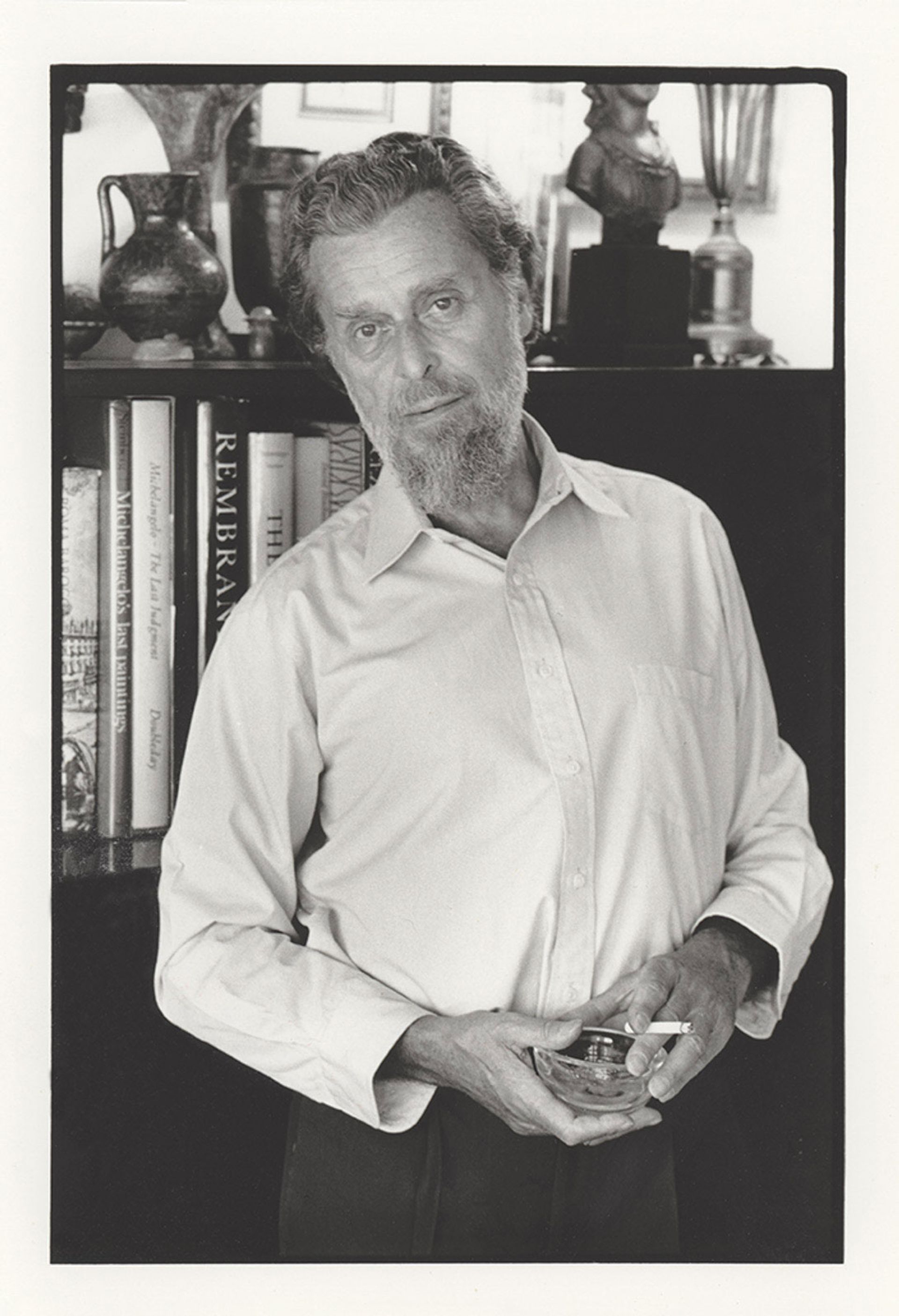

Leo Steinberg Photo: Lisa Miller

International inspirations

Born in Moscow in 1920, Steinberg was raised in Berlin from 1923 to 1933 and then relocated with his family to London, where he studied sculpture and drawing at the Slade School of Fine Art. Conversant in Russian and German, “he was determined to master English”, Borham says, and immersed himself in Shakespeare and James Joyce, developing a ruminative and idiosyncratic writing style enriched by metaphor.

In 1945 his family settled in New York, where Steinberg taught life drawing and toiled in freelance editing, writing and translation before finally settling on art history in his 30s. Writing exhibition reviews for magazines, he forged friendships with contemporary artists including Johns and Josef Albers. Steinberg was a late bloomer as an academic, earning his doctorate in art history at the New York University Institute of Fine Arts at the age of 40.

Around that time Steinberg began sifting through containers at New York print dealers’ shops, gradually amassing a collection that would ultimately span six centuries but was particularly focused on the period between 1500 and 1800. Steinberg also foraged for prints on trips to London and Paris, developing valuable contacts at a time when prime examples were still affordable.

“He took pride in discovering undervalued prints,” Borham says. “He collected what he could afford, for 50 cents or $2 or $5, while making $6,000 a year” as a part-time art history professor at Hunter College in New York. In the 1960s, Borham explains, prints were still underestimated as a genre, and “someone with a keen eye could still acquire important works”. Later, Steinberg became a professor of art history at the University of Pennsylvania.

The exhibition will include a section exploring how artists drew inspiration from widely distributed impressions of prints to generate their own art over the centuries, and will feature early woodcuts and engravings, etchings by Rembrandt and his contemporaries, atmospheric landscapes, and works by Modern masters such as Picasso, Henri Matisse and Joan Miró.

Léonard Gaultier's Last Judgment, after Michelangelo (1600-35) © Blanton Museum of Art; Leo Steinberg Collection

Last Supper interpretations

But the climax of the show will demonstrate the manner in which prints inspired Steinberg’s scholarship. For example, after comparing a variety of printed reproductions with Michelangelo’s Last Judgment fresco (1536-41) in the Sistine Chapel, Steinberg concluded that the original work offered sinners a reprieve from eternal punishment. While Michelangelo’s composition featured an intentional diagonal in which the soul could travel from sin to repentance to salvation, Steinberg observed that most engraved copies eliminated the diagonal and cancelled all hope of ascension for repentant sinners, in what amounts to a “theological correction”, Borham says.

In another revision by printmakers, some copyists drain the mystic eroticism from Michelangelo’s Pietà marble sculpture (1499), which Steinberg saw as “an exceptionally beautiful youth lying naked in the lap of a girl”. An etching by Jean Mignon from 1530-40 and a 1547 engraving by Antonio Salamanca, for example, leave the two figures less unified, retreating from what Steinberg saw as the mystical marriage between Christ and the Virgin.

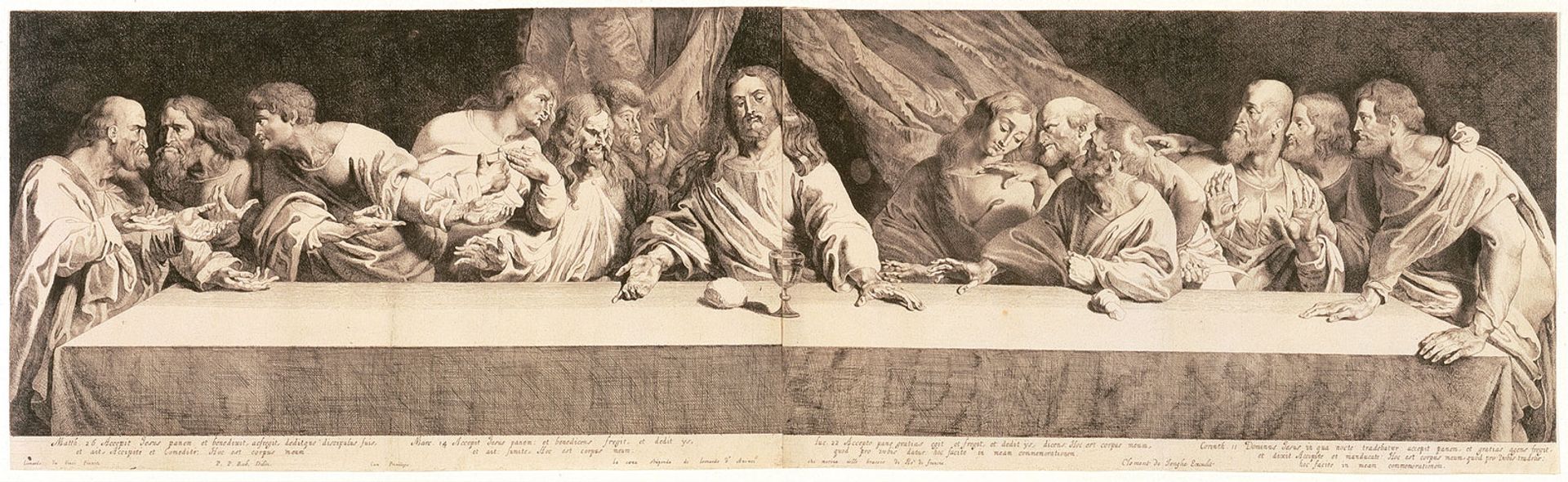

Pieter Claesz Soutman's Last Supper, after Peter Paul Rubens, after Leonardo da Vinci (1620-30) © Blanton Museum of Art; Leo Steinberg Collection

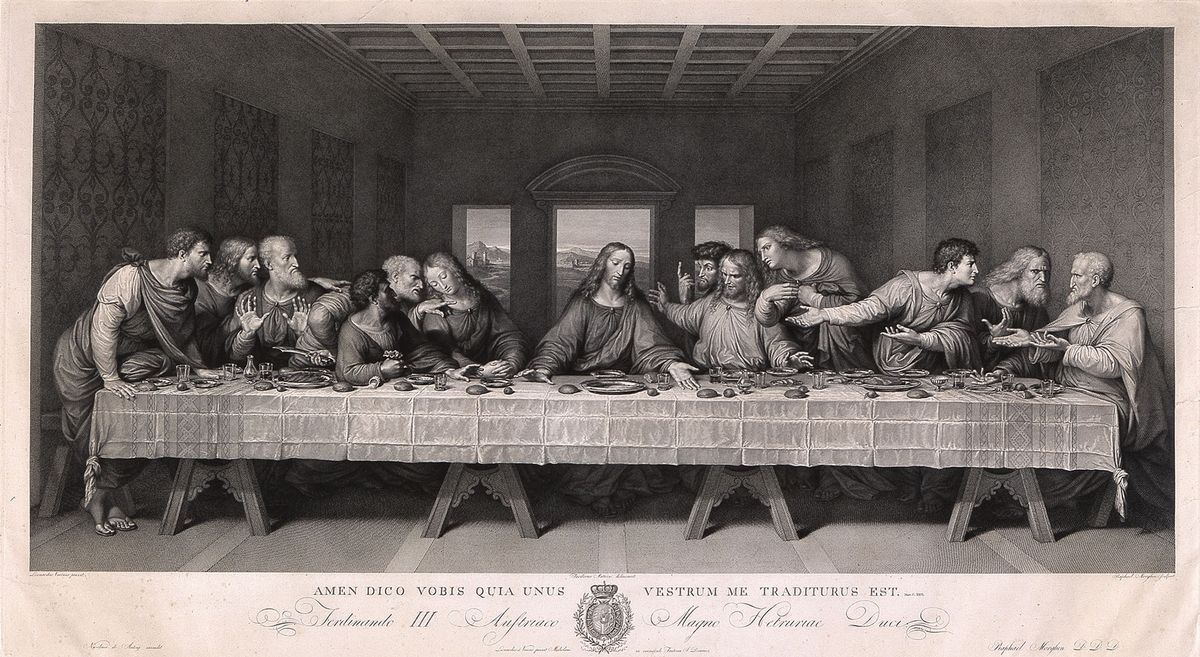

The show also delves into how Leonardo’s Last Supper fresco (1490s), which teems with possible interpretations of what exact moment is depicted, is reduced by most imitators to a single meaning. An 1800 etching and engraving by the artist Raphael Morghen removes the wine glass at Christ’s right hand, erasing the Eucharistic interpretation, and adds a caption identifying the moment as Jesus’s prediction of his betrayal, Steinberg noted. However, Peter Paul Rubens cleared the table except for the bread and wine, strictly emphasising the sacramental, as reflected in a 1620-30 etching by Pieter Claesz Soutman imitating Rubens’s print.

The exhibition will also wryly observe how a contemporary standout in Steinberg’s collection, Johns’s Painted Bronze (Ale Cans), was reproduced on the cover of the art historian’s 1963 book on Johns and then reappropriated by the artist in a 1964 lithograph recalling the book jacket illustration and its background colour. “In a reversal of the prints-to-scholarship direction, here Steinberg’s scholarship could be said to have occasioned a print, which Johns gave to Steinberg as a gift,” Borham notes.

Major funding for the exhibition and a forthcoming catalogue is provided by the Getty Foundation.

• After Michelangelo, Past Picasso: Leo Steinberg’s Library of Prints, Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin, 7 February-9 May