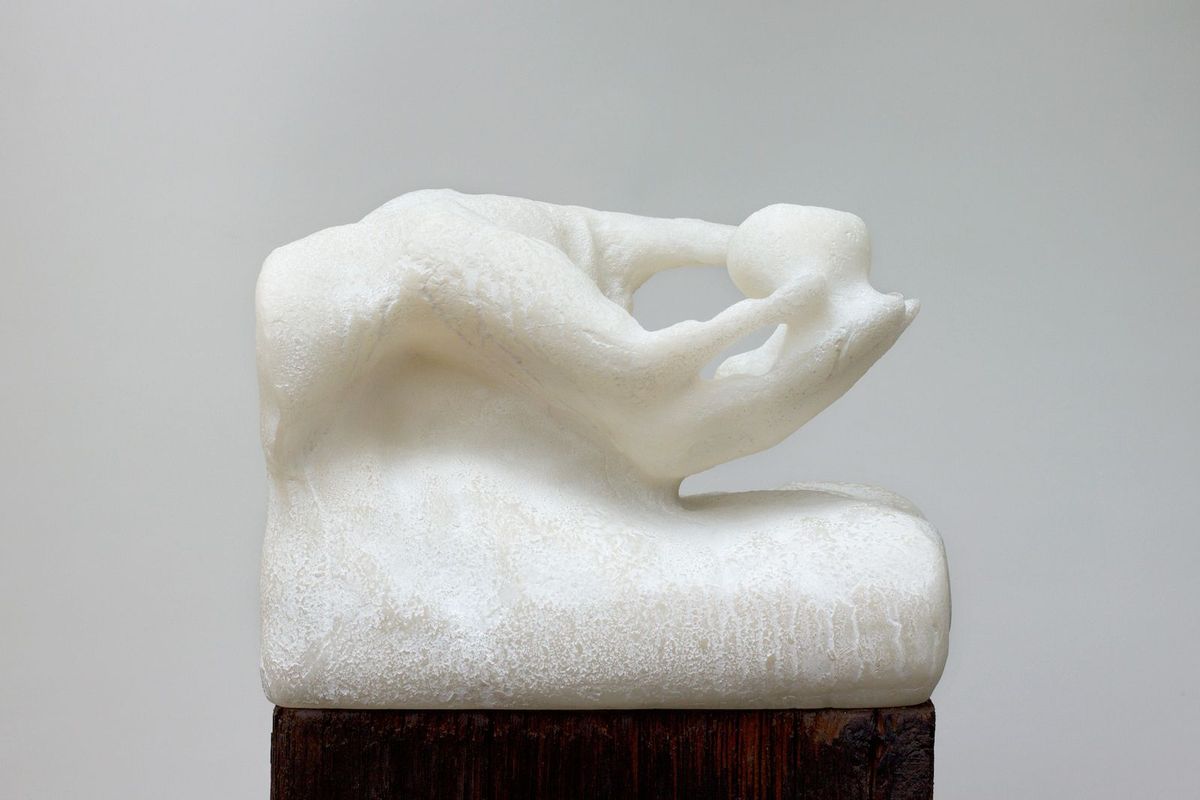

Malia Jensen: Nearer Nature

Until 3 April at Cristin Tierney, 219 Bowery Floor #2, Manhattan

This show represents the culmination of a multi-year project for the artist, whose work often probes into the gray area between the human world and the natural one, pointing to the poetic symmetry between the two. The work began in early 2019, when Jensen carved sculptures from livestock salt licks and installed them in the wilderness throughout Oregon state. The salt licks were carved into a number of forms, some, such as a plate of donuts, recall the domestic and mundane, while others shaped as a hand or a breast invoke tender, life-nurturing figures. When placed in this context, one salt lick carved in the shape of Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse evokes the relationship between humanity’s aspirations of beauty and nature’s innate mastery of it. Using over a dozen motion-triggered cameras, she monitored these sculptures as they sat in the wilderness for a year, watching not only as elk, deer, bobcats and other wild animals tasted and interacted with them, but also as the seasons changed and the objects ran through their natural course of deterioration. The footage was whittled down to a six hour video, which is on view in the gallery, and the five hand-carved salt licks were brought in from the forests and cast in glass, creating new sculptures that serve as small monuments to nature’s transformative power. —Wallace Ludel

Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell

Until 9 May at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, 26 Wooster Street, Manhattan

The first retrospective devoted to the late US artist Laura Aguilar, who is best-known for her empowered nude self-portraits taken in the desert, spans three decades of her practice, with more than 70 photographs, collages and videos. The show aims to underscore Aguilar’s activism in LGBTQ+ and Latinx movements in Los Angeles and the ways her work sought to challenge ideas of femininity and beauty. Early works like Xerox Collage #2 (1983), placing steamy cut-outs of actresses like Susan Sarandon against polaroids of Aguilar and her friends in Los Angeles, and later works like Grounded #111 (2006), in which the artist poetically likens her figure with the natural landscape, demonstrate how Aguilar approached her art and life with a raw but lyrical lens. The show has been organised with the Vincent Prince Art Museum, where it was previously on view, in collaboration with the Chicano Studies Research Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. —Gabriella Angeleti

But Still, it Turns: Recent Photography from the World

Until 9 May at the International Center of Photography Museum, 79 Essex Street, Manhattan

The museum is commemorating its first anniversary in the Lower East Side with an exhibition organised by the New York-based British photographer Paul Graham, comprising eight bodies of work that capture unembellished facets of American life in the past decade, from scenes of abandoned storefronts and cities ravaged by gentrification to idyllic moments of everyday life. Photographs in the series Index G (2014-2017) by the Italian photographers Piergiorgio Casotti and Emanuele Brutti reflect on racial segregation and the displacement of predominantly Black communities in the city of St Louis, Missouri, through images that show both subtle and glaring inequalities in the urban landscape. The photographs, which are devoid of human figures, are installed on opposing walls to create a flow that symbolises the movement of some communities to northern parts of the city, ending in a residential area known for radioactive contamination; at the centre of the gallery there are portraits of residents installed on plinths. And while all the works were made before the nationwide racial justice protests of the past year and the coronavirus pandemic, the show remains deeply resonant. —Gabriella Angeleti

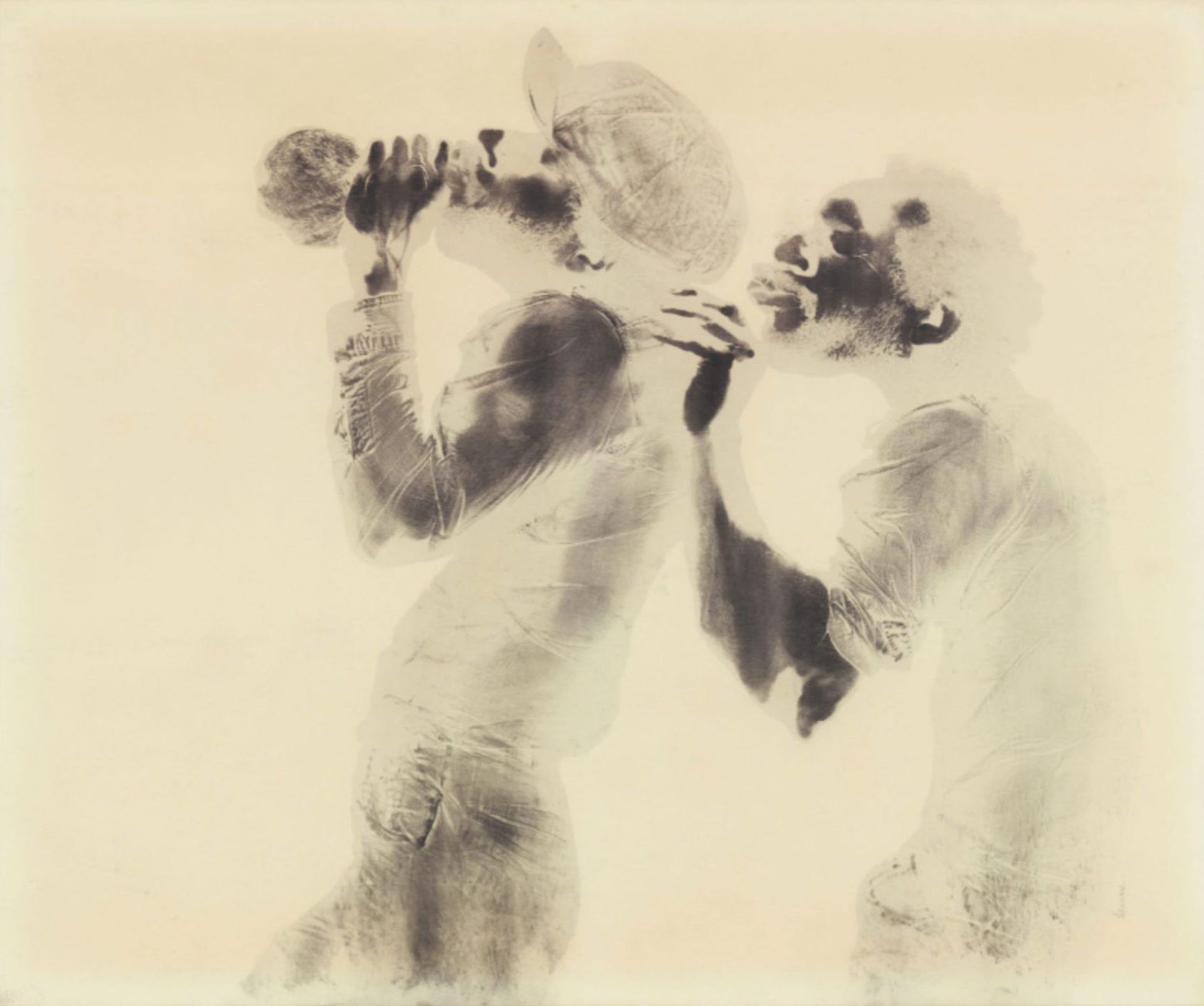

David Hammons, The Wine Leading the Wine (around 1969) The Drawing Center; Hudgins Family Collection, New York

David Hammons: Body Prints, 1968–1979

Until 23 May at The Drawing Center, 35 Wooster Street, Manhattan

The American conceptual artist David Hammons pioneered an unconventional method of printmaking in the 1960s by smearing grease—like margarine and baby oil—on human figures and pressing them against large-scale pieces of paper, then dusting the imprint with pigment. These “body prints” and other early works on paper, a foundational area of the artist’s oeuvre, are being examined in a comprehensive museum presentation for the first time but represent the genesis of his artistic practice, despite being lesser-known than his later assemblage pieces. The work The Wine Leading the Wine (around 1969)—in which the artist used not just bodies but also wine bottles, paper bags, gold chains, chicken bones and other materials—comments on the stereotypical prevalence of certain objects in predominantly negative stories dealing with African-American culture, a topic the artist continues to explore in the various manifestations of his practice. —Gabriella Angeleti

Philip Guston and Raymond Pettibon

Until 20 March at Brooke Alexander, 59 Wooster Street, Manhattan

In 1980, the year of his death, Philip Guston embarked on a series of black and white lithographs. Through primarily studio still-lifes, Guston displayed that lithography was a wonderful vessel for the gestural, representative style that was consistent in his later work. The same year, Raymond Pettibon—then in his early twenties—was beginning to make waves as the artist behind the album covers of the now legendary punk band Black Flag, who were founded by Pettibon’s brother Greg Ginn and who had released just their first two EPs in 1979 and 1980. In this exhibition, the gallery has smartly paired the two artists’ lithographs together for a two-man show. Though each style is unique and instantly recognizable, with their lithographs placed side by side, Pettibon and Guston’s distinctive hands dance in rewarding ways as both use their painterly tendencies and their smart high-and-low humor to probe the tragicomic tendencies of the American experience. —Wallace Ludel

Goya’s Graphic Imagination

Until 2 May at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan

The show comprises more than 100 prints and drawings by the Spanish master Francisco de Goya that chronicle his development as a draftsman and printmaker, from his early career at the Spanish court to later politically-charged works. Among the most compelling pieces, works from the haunting series The Disasters of War (1810–20)—in which Goya, in his signature style, conjoined the wondrous with the macabre—show a carnival of violence that condemn the consequences of warfare. The series of more than 80 etchings were partly made amid the Spanish War of Independence and were deemed so controversial they were only published decades after Goya’s death in 1828; some scholars speculate he wanted to hold the publication of the images until the works could be seen uncensored, and due to fear of punishment from the Spanish king Ferdinand VII. Most pieces in the exhibition have been pulled from the museum’s permanent collection, which holds the largest collection of works on paper by Goya outside of Spain. —Gabriella Angeleti

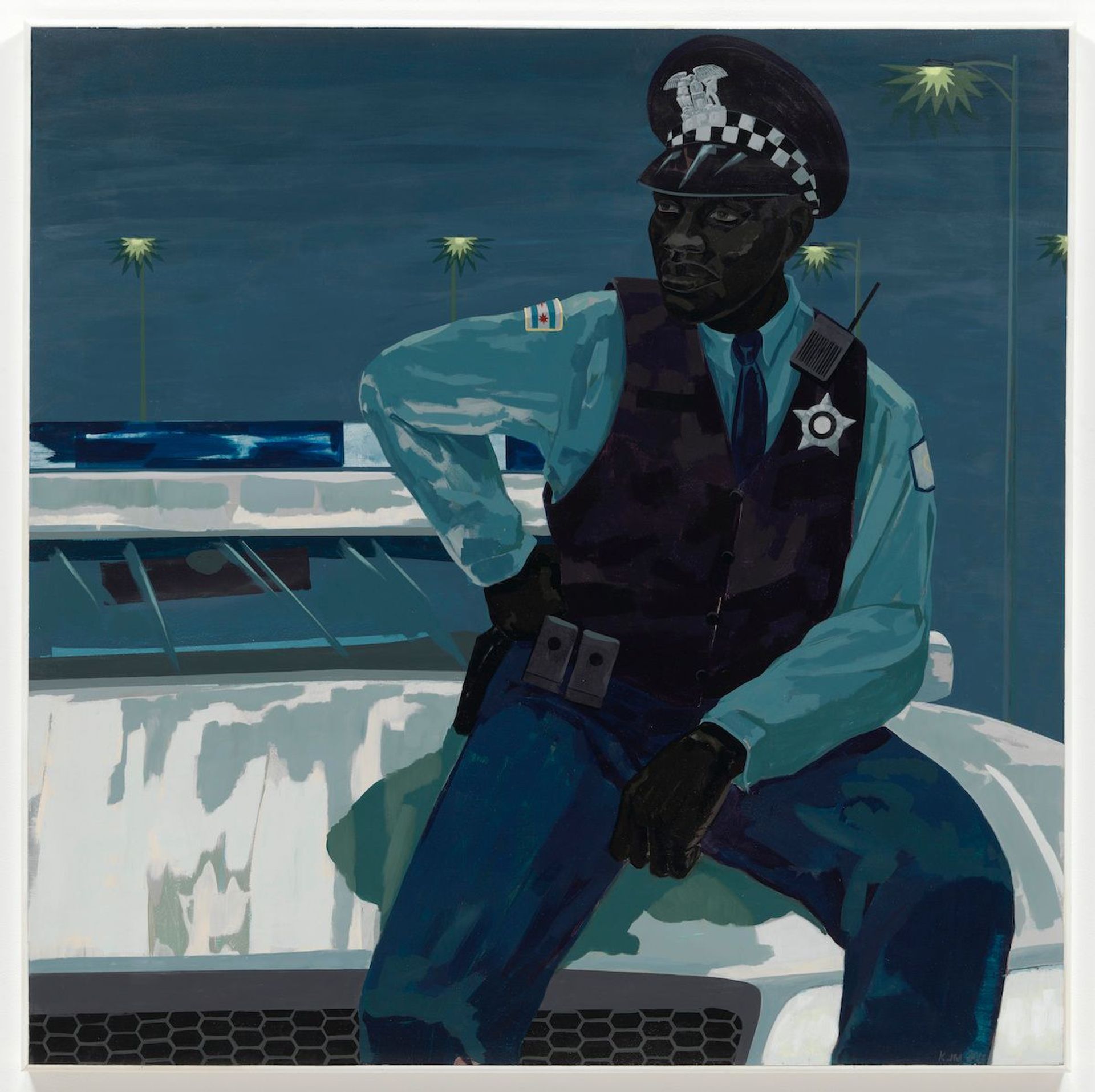

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Policeman) (2015) Photo: Jonathan Muzikar; courtesy New Museum

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America

Until 6 June at the New Museum, 235 Bowery, Manhattan

The late curator Okwui Enwezor, a chief advocate for Black artists throughout his prolific career, envisioned that this poignant exhibition responding to racial violence in the US would be timed to the 2020 presidential election to underscore the epidemic of white nationalism that was long brewing in America but heightened during the Donald Trump administration. Although the show was postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic, the events that unfolded throughout the year give the exhibition even more urgency. Massimiliano Gioni, the New Museum’s artistic director, and Naomi Beckwith, the deputy director and chief curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, as well as the artists Glenn Ligon and Mark Nash, curated the show in Enwezor’s vision, bringing together the work of nearly 40 artists, from Jean-Michel Basquiat to Kerry James Marshall, that deal with incarceration, police brutality, the normalisation of white supremacy and other issues. In his plan for the show, Enwezor wrote that there was a need to “assess the role that artists, through works of art, have played to illuminate the searing contours of the American body politic”. —Gabriella Angeleti

Peter Joseph: The Border Paintings

Until 24 April at Lisson Gallery, 504 West 24th Street, Manhattan

The first posthumous exhibition devoted to the British artist Peter Joseph, who is best-known for creating harmonious two-colour paintings contrasting rectangles and squares, features a series of works from the 1980s and 1990s that create a sublime, meditative space in the gallery. Joseph died in November last year while preparing for the show, which was slated to include later works demonstrative of his departure from hard-edge abstraction; but this collection of signature works represent the breadth and legacy of his practice. The artist said the pieces were inspired by Classical music and architecture, Renaissance masterworks, and the psychologically impactful work of artists like Marth Rothko and Donald Judd. When asked to describe the painting No.55 Green with Dark Blue Surround (1981)—which is now held in the collection of the Tate in London—he wrote: “There is little space left in the industry of art for exhibiting for a dream or reverie. What you see in my work is perhaps a momentary attempt to establish this place.” —Gabriella Angeleti

Mira Dayal: …In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province…

Until 4 April at Spencer Brownstone Gallery, 170-A Suffolk Street, Manhattan

Mira Dayal’s installation is named for Jorge Luis Borges’s short story On Exactitude in Science. The show’s title is, in fact, the entirety of the four sentence-long story, which tells the tale of a map sized at a one-to-one scale to the land it delineates, rendering it both incredibly accurate and entirely useless. Like the story, the show poses a number of poignant questions into not only the history of mapmaking and colonisation, but also the very concept of place and our relationship to it. The entire gallery floor has been rubbed by hand with a layer of graphite, laboriously creating a one-to-one topography of the space itself, which tells us both everything and nothing about it. Mounted above the floor are 12 fans that allude to the 12 winds—an ancient geographic system first laid out by Aristotle—and a real weathervane outside the gallery triggers individual fans on and off, based on the direction of the wind. That something so grand as wind can be replicated here at a human scale, with some hardwired metal fans and a weathervane, speaks to the comic implausibility of the world, our attempts to master it, and the endless reach of our desire as we pass through it. —Wallace Ludel

Guadalupe Maravilla, Ancestral Stomach (2021) PPOW

Guadalupe Maravilla: Seven Ancestral Stomachs

Until 27 March at PPOW, 392 Broadway, Manhattan

The Brooklyn-based Salvadoran artist Guadalupe Maravilla recalls how a chemotherapy appointment in New York left him nearly unable to walk, and how a sound bath he encountered on the way home led to a years-long sound therapy treatment that he credits for his successful recovery from colon cancer in 2013. In this exhibition for the gallery’s newly inaugurated space in Tribeca, Maravilla has produced a series of esoteric and deeply personal retablos, sculptural “stomaches” and free-standing sculptures rich with spiritual symbolism. Some works generate vibrational sounds and are made from materials collected throughout Central America, simultaneously referencing the artist’s personal history of crossing the US border and his solidarity with the pain and trauma experienced by undocumented immigrants. The show follows Maravilla’s first museum exhibition at ICA Miami, where the artist presented a series of large-scale sonic sculptures that similarly evoked healing and cleansing instruments. —Gabriella Angeleti

Roni Horn: Recent Work

Until 10 April at Hauser & Wirth, 542 West 22nd Street, Manhattan

Roni Horn is a unique artist whose work across virtually every medium manages to encapsulate her sensibilities—her desire for awe, her humour, her love of the poetic—while translating each of them into different kinds of work with an enigmatic touch. In this exhibition, Horn is showing only drawings and work on paper. On view are works from the artist’s Wits’ End series, her Yet series and the massive 406-part drawing LOG, which is arguably a series unto itself. LOG is a diaristic suite of drawings completed daily between March 2019 and May 2020 and displayed together as a single installation. The work maps the passage of time in a manner that recalls On Kawara’s Date Paintings or Byron Kim’s Sunday Paintings, but the touch is uniquely Horn’s. Photography, drawing and collage coalesce into a portrait of grace, grief and time, things that we may have an abundance of at this moment in history. —Wallace Ludel

David Goldblatt: Strange Instrument

Until 27 March at Pace, 540 West 25th Street, Manhattan

The artist Zanele Muholi has curated the first posthumous US exhibition devoted to the South African photographer David Goldblatt, who pointedly explored the complexities and grotesqueness of apartheid throughout his seven-decade career. Muholi, who considered Goldblatt a “mentor, friend and father figure”, has selected more than 40 photographs from the 1970s and 1980s that capture the contradictions Goldblatt observed between the lives of white and Black South Africans. The son of Lithuanian-Jewish immigrants, Goldblatt often felt alienated as a teenager and began to photograph the miners and landscape of the white-only town where he was born. Although he did not consider himself an activist, his desire to navigate and document a world that others did not, or could not, resulted in some of the most invaluable records of apartheid and the liberation movement. The show has been organised in collaboration with Yancey Richardson Gallery, which represents Muholi. —Gabriella Angeleti