Raphael’s seven surviving tapestry cartoons for the Sistine Chapel were photographed for the first time in 1858. Lowered from a window of Hampton Court Palace, where they had been on and off display for more than 150 years, the Raphael Cartoons (1515-16) were documented by daylight on glass plate negatives over several months. The delicate task was commissioned by Prince Albert, whose passions for Raphael and photography led him to amass a study collection of 5,000 reproductions of the master’s works.

In August and September 2019, the cartoons were recorded once again with cutting-edge technology, this time with high-resolution colour photography, infrared and 3D scanning. Factum Foundation led the five-week project behind the closed doors of the Raphael Court at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London—home to the cartoons since Queen Victoria decided to lend them in memory of her husband. It was “like a military operation”, says Factum’s founder, Adam Lowe, as the recording had to be coordinated with V&A conservators leading condition checks and Momart technicians removing the vast glass frames from two cartoons at a time.

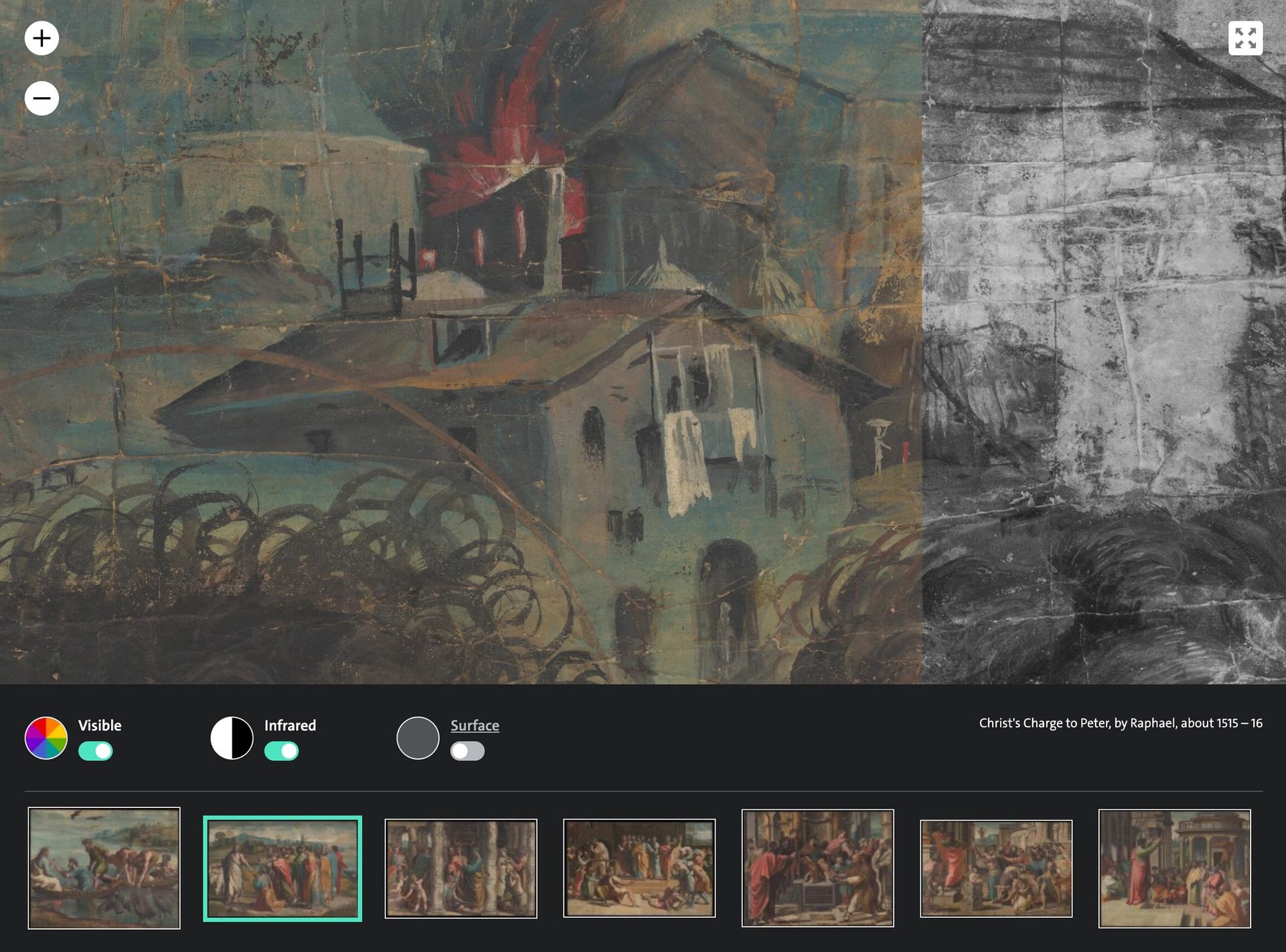

Factum Foundation spent five weeks in summer 2019 recording the Raphael Cartoons, including Christ's Charge to Peter, with panoramic composite photography, infrared and 3D scanning © Gabriel Scarpa for Factum Foundation

The high-resolution images captured are now available to browse online as part of the museum’s new digital interpretation of the cartoons. In-depth digital features on the making and history of the works were launched today (25 January) on the V&A website, ahead of the physical reopening of the Raphael Court, which awaits the lifting of UK coronavirus restrictions.

Last year, in honour of the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death, the V&A undertook a refurbishment of the gallery that aims to make the cartoons “more visible and legible”, says the project’s curator, Ana Debenedetti, with a bold wall colour to enhance Raphael’s “beautiful palette” and new LED lighting to minimise reflections on the glass. “It was about time” to redecorate, she says. The old lighting was installed during a 1996 renovation and had gone out of production, making it impossible to replace broken bulbs.

Hung on high and behind glass, Raphael’s scenes from the lives of saints Peter and Paul can nevertheless be hard to see. But the new digital interpretation has unlocked an “incredible level of detail” thanks to Factum’s images of and beneath the painted surface, Debenedetti says.

An online detail in colour and infrared of Christ's Charge to Peter © V&A Courtesy Royal Collection Trust HM Queen Elizabeth II 2021

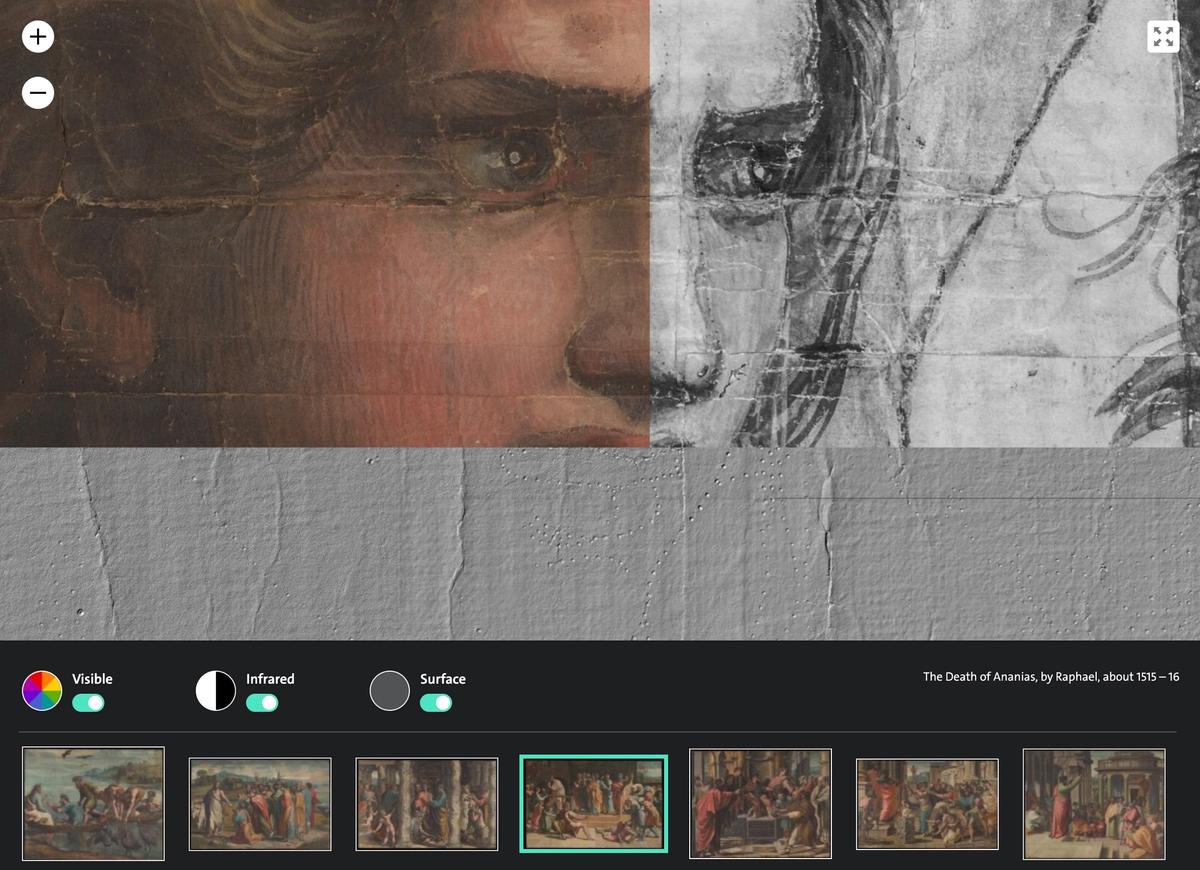

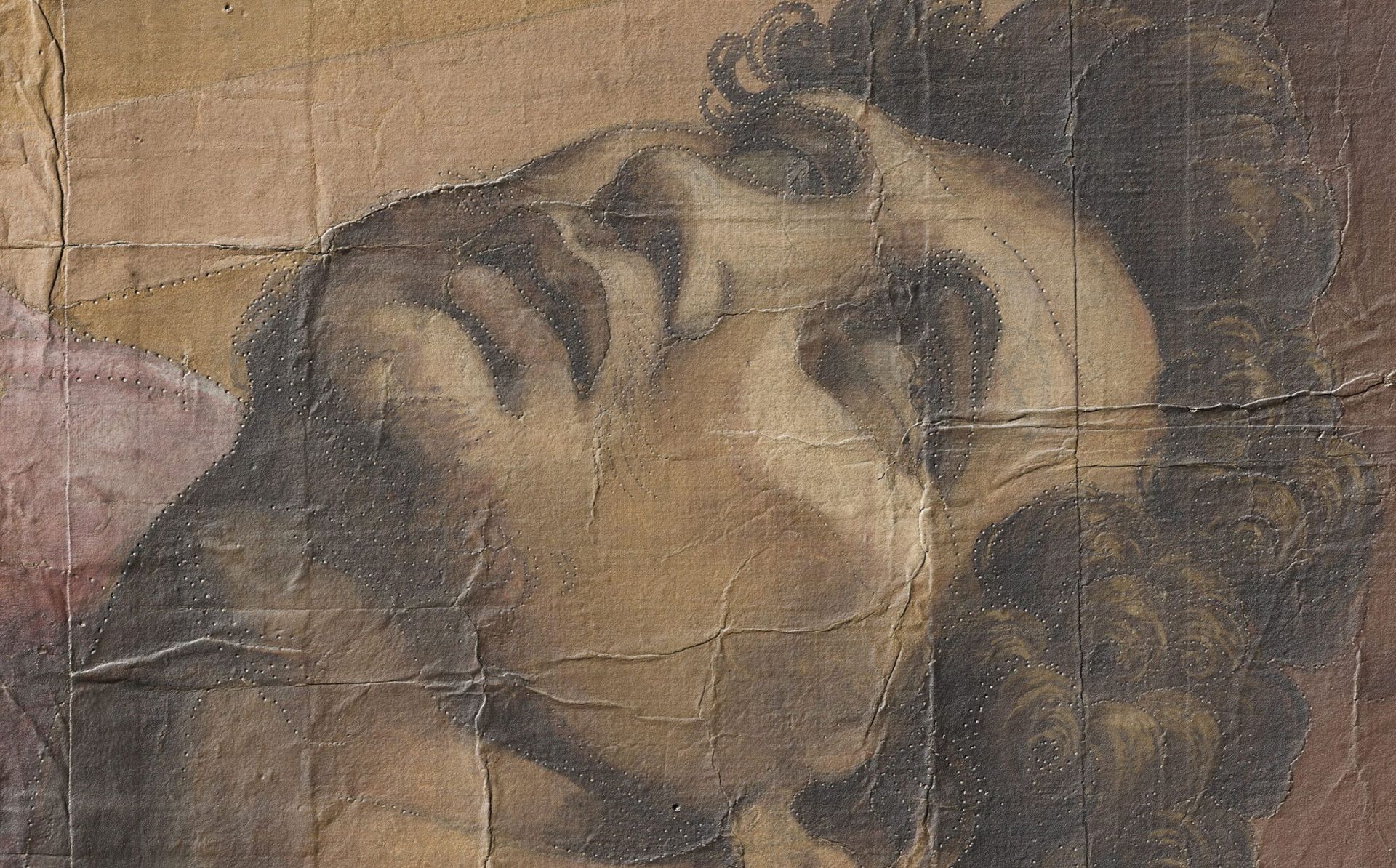

On the V&A's website, a feature called Explore the Raphael Cartoons includes interactive browsers that visualise the colour, infrared and 3D layers of the cartoons. Users can zoom in to see the tiny pinholes that were crucial to the 16th-century creative process of translating Raphael's full-scale painted designs into tapestries, which were woven by Pieter van Aelst’s workshop in Brussels.

High-resolution imagery lays bare the “dramatic” texture of the works, Lowe says, which “make a [Anselm] Kiefer painting look flat”. Each cartoon measures roughly 5m by 3.5m, made up of around 200 sheets of paper glued together. The 3D scans of the collaged surfaces “take you back 500 years, when the last people to see that were Raphael and his team of apprentices”, Debenedetti says. “Emotionally, it’s something we’ve never been able to offer visitors before.”

A detail of The Death of Ananias reveals the minute pinholes used to transfer Raphael's composition to a template for the tapestry weavers in Brussels Photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Courtesy Royal Collection Trust / Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Raphael’s large studio worked fast to create the series of ten cartoons (three had been lost by the time they came to England in 1623) in just 18 months. Factum’s greyscale infrared images show preparatory drawings in black chalk or charcoal that are not visible to the naked eye, including the pentimenti when, for instance, a hand was sketched in different positions before being finalised, and “the typical flurry of lines of Raphael’s graphic style”, Debenedetti says. “You will be able to observe the artist at work, building up the picture.”

When the Raphael Court is permitted to reopen, visitors will be able to scan QR codes with their smartphones to access the high-resolution browsers and a host of interactive features, including a timeline of the cartoons’ history, a “spot the difference” game for families to compare the cartoons with the Vatican tapestries, and explanations of the religious iconography—intended to affirm the leadership of the pope as heir to Peter and Paul, the founding fathers of the Christian Church.

The Death of Ananias, one of Raphael's seven surviving full-scale painted designs on paper for the Acts of the Apostles tapestry series, depicting the lives of saints Peter and Paul Photo: © V&A; courtesy Royal Collection Trust Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Debenedetti hopes that mobile access will transform the way visitors engage with the cartoons in the gallery. “The public is eager for more interaction,” she says. “The only way was to provide a digital offer that would guide you to go back and forth between the information and the work itself.”

Despite the age, fragility and consistent display of the cartoons, conservators found them to be in “amazing condition” last summer, Debenedetti says. However, she acknowledges that they “might not survive forever, so it’s our duty to record them in the best possible way”.

Factum’s digital data offers a preservation tool for future generations. They also open up intriguing possibilities to replicate works that are too vulnerable to travel. With permission from the V&A and the Royal Collection Trust, Factum 3D-printed a facsimile of one cartoon, The Sacrifice at Lystra, for the major Raphael exhibition held at Rome's Scuderie del Quirinale last year. The technology represents a “new kind of sharing”, Lowe says, “for people all over world to see these paintings”.

UPDATE: This article was updated from an earlier print version, published in November 2020.