Sam Herman was a multi-talented artist whose work with glass, together with his influence as a teacher, freed that medium from the confines of the factory and enabled the nascent studio glass movement to flourish internationally in the 1960s and 1970s.

The combined development of a suitable glass formula and the “small furnace”—first demonstrated by the studio glass pioneer Harvey Littleton at Toledo Museum of Art in 1962—allowed artists to work directly in the mercurial medium of hot, molten glass, where before they might typically have passed drawn designs to professional glassmakers, restricting their creativity. Herman studied with Littleton, and with the sculptor Leo Steppat, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he seized the opportunity, as one of Littleton’s first students, to develop studio glass techniques, and received a Master of Fine Arts in Sculpture and Glass in 1965. He then won a Fulbright Scholarship to study cold-working glass techniques with Helen Monro Turner at the Edinburgh College of Art.

Determined innovator

In 1966, Herman enterprisingly brought an exhibition of new studio glass from his fellow students at Wisconsin to Edinburgh, the Stourbridge College of Art in the Midlands, and the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. David, Marquess of Queensberry—then the head of ceramics at the RCA—saw the show and invited Herman to take up a research fellowship at the college. The following year, Herman became head of the newly renamed Glass Department, at a time when the RCA was a crucible of experimentation, and his colleagues included Carel Weight, Eduardo Paolozzi, Peter Blake and Hans Coper. Herman was a determined innovator. “In the 60s,” he said, “anything was possible.” It was also the time when he found his vocation for teaching, one that took him across the world.

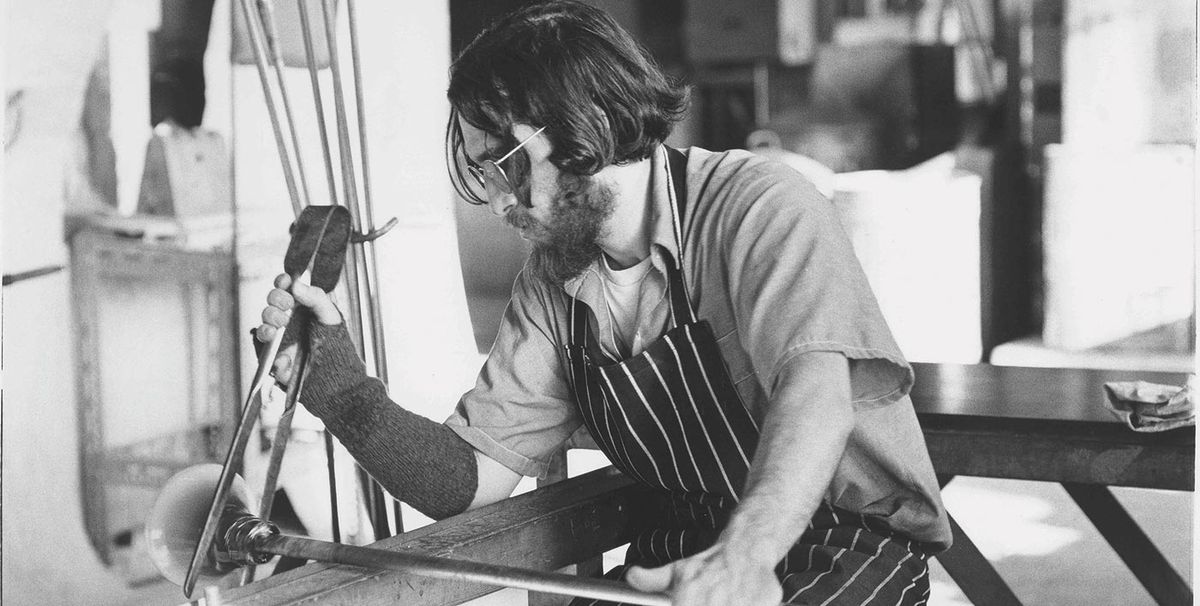

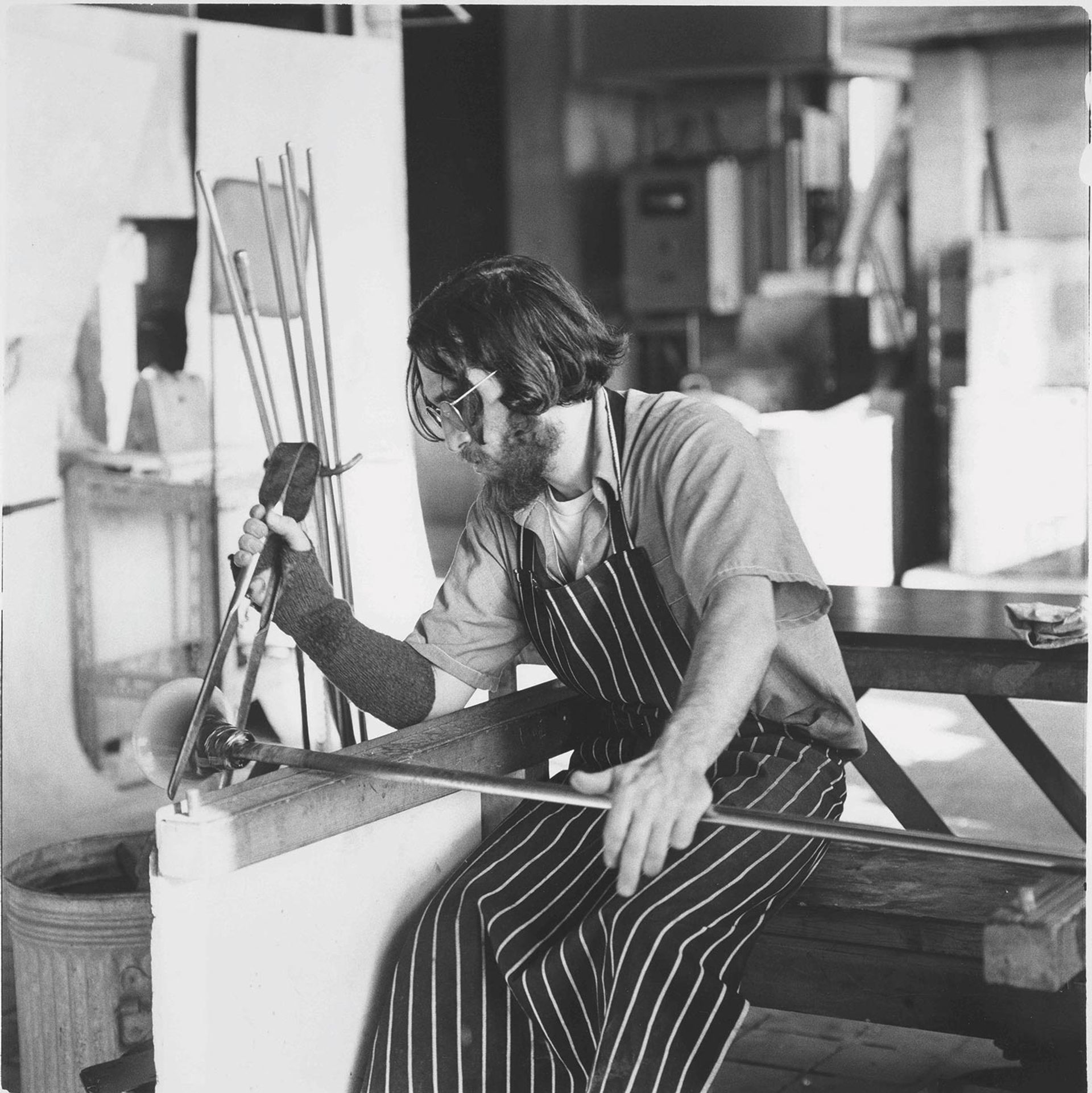

Sam Herman at the Royal College of Art, London, where he was head of the Glass department, 1967-74 Courtesy of the Frestonian Gallery

Both Herman and his students learned by doing and became the first manifestation of artists in Britain who chose to express themselves with glass. His student Clifford Rainey recalled that Herman “practised tough love” as a teacher, but “he always had your best interest at heart”. Learning by taking risks and making mistakes was encouraged, but Herman “expected conceptual rigour, technical expertise and material investigation. He would teach by example... I would be in awe, watching him at the bench balancing large gobs of molten glass on a blow pipe, adding colours and minerals, not unlike how an Abstract Expressionist would, then working the mass to give a sculptural form. It was inspirational.”

A New York upbringing

Herman was born in 1936 in Mexico City, to a Jewish Polish émigré mother who never revealed the identity of his father. They moved to Queens, New York, when he was eight years old. After a stint in the US Navy—he had become a US citizen in 1946—he studied anthropology and sociology at Western Washington State College, but became increasingly interested in art, which took him to Madison and his life-changing encounters with Littleton and Steppat.

Herman’s first major exhibition was in 1967 at the Primavera Gallery, in Sloane Street, London. It sold out, and the gallery continued to stock his work, which was often displayed alongside ceramics by his peer Hans Coper. Exhibitions followed in other countries, including one at the Seibu department store in Tokyo in 1969, organised by the Crafts Council. In 1970, Galerie L’Ecuyer in Brussels, owned by the collectors and dealers Gilbert Weynans and Hubert Muerrens, invited him to exhibit. This led to a partnership in which designs by Herman were made at the Belgian glass company Val St Lambert.

In 1971 the Victoria & Albert Museum in London held a major exhibition of Herman’s glass art, together with jewellery by Gerda Flöckinger, a show that made him realise how far he had come in a short period of time. “As I wandered in [to the museum] I passed through the galleries and realised that there was 2,000 years’ worth of amazing art here, and people were passing it on the way to see my glass,” he said. “That was quite a jolt.” It also made him the first contemporary glass artist and the first living glass artist to be given an exhibition at the museum. Around 30 international exhibitions followed in the succeeding years, including at The Fine Art Society in London.

From The Glasshouse to the Jam Factory

Herman realised the importance of access to a furnace and a sales venue in the development of graduate glass artists. “I feel a moral obligation to my students,” he said. “Where can they go when they leave college?” With that in mind, in 1969 he had co-founded, with Graham Hughes, The Glasshouse in Covent Garden, London, where artists could both rent furnaces, and sell their work in the gallery. The success of this venture, and his growing reputation, led to Herman being invited by the South Australian government in 1974 to found the influential glass studio at the Jam Factory, in Adelaide, which, like the Glasshouse, allowed waves of artists in glass to forge careers of their own.

Herman remained at the Jam Factory until the atmosphere there changed, because of financial pressures, and his first marriage broke up. In 1979, a patron helped fund his return to London and found his own glass studio in Lots Road, Chelsea. Enjoying “total freedom”, he entered one of the most prolific periods of his life, and also met and later married his second wife, Joanna Shellard. He became a British citizen, jointly with his US citizenship, in 1994.

The human torso is a very beautiful thing. The way a person postures themselves reveals their personality… Once you start playing around with that, it becomes interestingSam Herman

At the heart of Herman’s own works in glass lies a fascination with the torso. “The human torso is a very beautiful thing,” he said. “The way a person postures themselves reveals their personality… Once you start playing around with that, it becomes interesting.” However, some forms clearly appear more functional than sculptural, such as the vases, bowls and platters he made. About these, he said, “Regardless of what they are, they are an expression of myself. I don’t make the distinction between fine art and crafts… it’s a work of art whether it’s a doorknob or sculpture.” Some were also dynamic explorations of colour and pattern, created by melting in coloured powders, chips or threads and sometimes mirroring or fragmented gold leaf. His novel use of silver chloride modified colours or gave an iridescent effect. Herman sometimes worked to preconceived thoughts or preparatory sketches, but he also allowed the glass itself to contribute. “Glass is a dance of immediacy,” he said.

Sam Herman, Untitled, blown glass, signed and dated 1979, both 30cm (11.75in) high, Private Collection Photograph: © Sylvain Deleu 2018

Herman followed Henry Moore’s ethic of “truth to materials”, and the inherent qualities of glass as a material were allowed to manifest in his work. “Why make glass look like something that it isn’t?” he asked. “That’s what the studio glass movement was about—using a material in the most natural way possible. But, most importantly, to use it in a creative sense, and in as artistic a sense as possible.”

In 1984 Herman closed his glass studio to focus on sculpture and painting. His glassmaking tools were packed away until his sporadic return to working with hot glass from 2007 to 2017.

Sam Herman, Untitled, blown glass, signed and dated 2013, 37cm (14.5in) high, Private Collection Photographe: © Sylvain Deleu 2018

Studying under Steppat in the 1960s had introduced Herman to sculpting in welded steel, at the time a recent innovation. He was inspired by the work of Lynn Chadwick, Kenneth Armitage and others. His spiky, textured metal sculptures, typically of animals, are both semi-abstract and semi-figurative. Later, glass was combined with steel, creating a dichotomy between the fragile and the strong. And he worked with light, which was essential both to his work in glass and his lighting sculptures, which sometimes echo stained-glass windows with their angled lines and jewel-like colours.

Why make glass look like something that it isn’t? That’s what the studio glass movement was about—using a material in the most natural way possible. But, most importantly, to use it in a creative sense, and in as artistic a sense as possible.Sam Herman

Herman began to paint in 1984. Vibrantly coloured figurative or semi-abstract forms sit on flat surfaces with no recessive space or perspective, and the flat nature of the canvas is accentuated with collaged elements and added texture. Some works refer to his glass forms, some to landscapes or personal memories, and some are tinged with Surrealism.

Sam Herman was shaggy and bearded, virtually defining the word “hippie”, but he was also firm, decisive and particular. This was evidenced in his work, nowhere more than with his glass art. There is no such thing as a Sam Herman “second”—all unsatisfactory pieces were smashed. “I just instinctively know when something works, and when something doesn’t work.”

Sam Herman working at London Glassblowing in 2012 © Martin Storey

Sam Herman was endlessly creative, always doing something with his hands. He found beauty in both form and detail, from the sculptural ceramics of his erstwhile colleague Hans Coper to intricately carved netsuke. He was highly gregarious and fascinated by people. Their differing postures inspired many of his sculptural art glass forms, which can be seen today in major museums around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, testament to his leading role in a movement that changed the course of 20th-century decorative arts. He is survived by Joanna, and his children Sarah and David.

• Samuel Jacob Herman, born Mexico City 25 July 1936, died Lechlade, Gloucestershire, 29 November 2020