One of the biggest challenges for police and customs officials in combating the illegal trade in looted antiquities is in identifying stolen objects. While drugs or weapons are readily identifiable as illegal imports, stolen antiquities can be passed off as modern copies or legitimate imports if they are accompanied by convincing documentation. Without expert archaeologists on the spot, it is hard for law enforcers to know the difference.

German information technology experts are developing an app to help them, and a prototype may be ready for practical trials by the middle of the year, says Martin Steinebach, the head of media security and IT forensics at the Fraunhofer Institute in Darmstadt. The new app, known as KIKU, uses machine learning—a subset of artificial intelligence (AI)—to identify an object from photos and to help to ascertain whether it may have been illegally looted or excavated from an archaeological site.

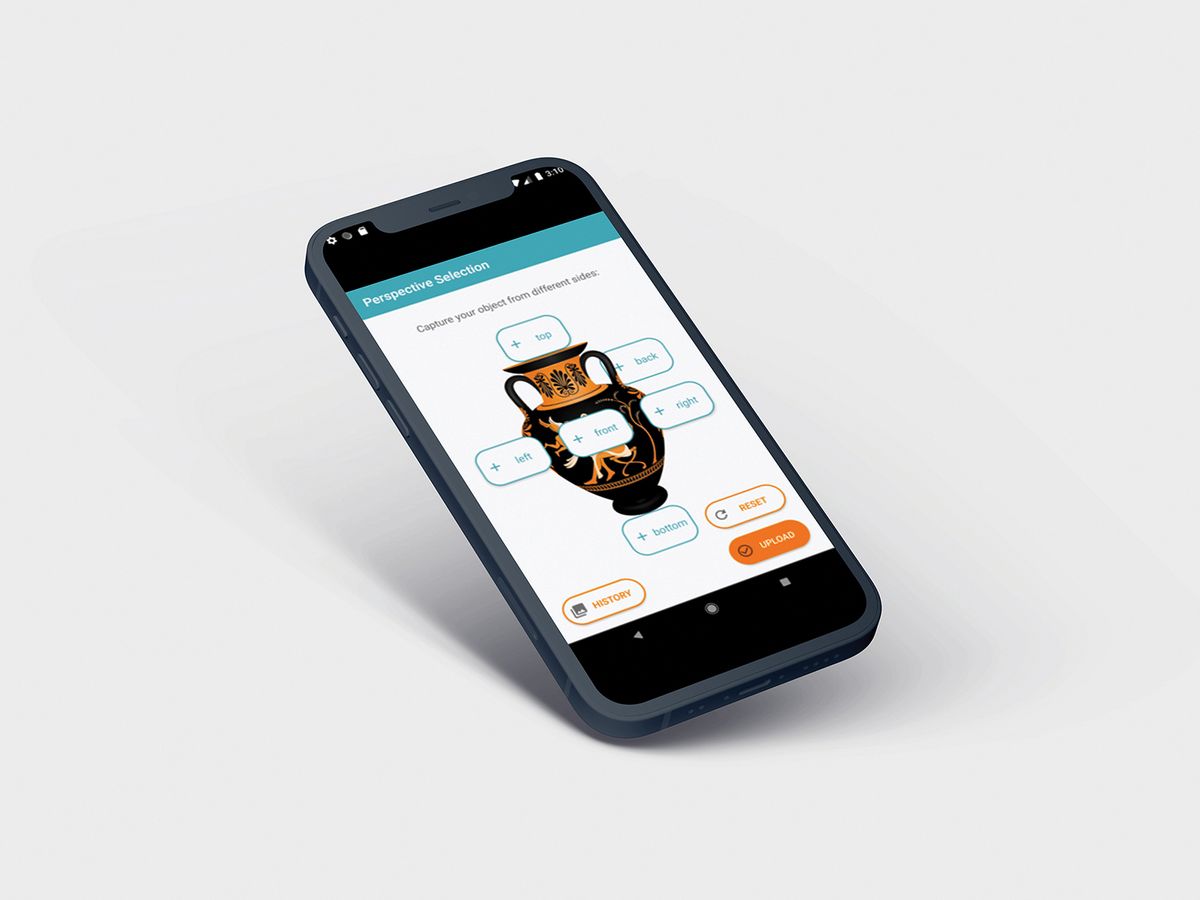

The technology is similar to other image-recognition software such as Google Cloud’s Vision and can be operated on a smartphone, Steinebach says. Police or customs officers take photographs of a suspect object from a variety of angles, guided by the app to ensure adequate lighting and the correct perspectives.

The photos are then sent to KIKU’s deep-learning network, which searches for similar artefacts and relevant information from archaeologists—such as place of origin and date. This provides an initial basis for law enforcers to judge whether the item might be looted. In a second stage, the app compares the object with police databases of stolen cultural property; Interpol’s, for instance, contains more than 51,000 stolen objects from 134 countries. If there is a match, the app sounds an alarm.

Described by German Culture Minister Monika Grütters as an “innovative, sustainable and practical contribution” to the fight against the illegal trade in cultural heritage, KIKU has won funding of up to €500,000 from a government programme to promote AI technology in a project running until the end of this year. The Fraunhofer Institute, one of the biggest scientific research organisations in the world, is developing KIKU in co-operation with CoSee, a Darmstadt-based software company.

"Effective technological tools could “significantly relieve the burden on customs authorities, experts and investigatory agencies.”

In 2018, Interpol registered more than 91,000 stolen items of cultural heritage and almost 223,000 items seized by law enforcement agencies worldwide. The starting point for KIKU was a German government-funded research project, ILLICID, which examined the trade in ancient cultural objects in Germany. Among the findings was that investigating agencies and supervisory authorities lack the expertise to address the illicit trafficking in ancient artefacts.

“It is not currently possible to efficiently monitor the trade or to appropriately enforce existing and/or new due diligence requirements governing the handling of ancient cultural objects,” the report says. Effective technological tools could “significantly relieve the burden on customs authorities, experts and investigatory agencies”.

KIKU uses the data and images provided by archaeologists at the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation for around 2,500 antiquities in the Berlin collections. But that is a relatively small pool of images and it requires many more, says Steinebach: “At least ten times that” is needed. “The app can learn distinctive scripts or shapes. If we have enough examples, the app can recognise them. The more images there are, the better it works.” In addition, the team is using “transfer learning” from existing networks and adding artefacts from online museum databases and catalogues.

As an example of how the app could work, Steinebach says that if an object is imported with forged provenance documents, it may be possible to prove they are fake if KIKU enables customs officials to identify the object correctly. “Say the documents claim it is from the 16th century but the app identifies it as dating from 600BC—that gives customs officials a very good starting point,” he says. The app is not designed to detect forgeries, he adds.

One key challenge is the lack of existing records for recently excavated antiquities. However, as long as an object bears a resemblance to other known items of the same epoch, the app should be able to identify its place of origin and age, Steinebach says. “But you never know what might have been excavated; it could be something the like of which has never been seen before.”

Steinebach doesn’t expect that the app will eradicate the need for archaeology experts in identifying objects any time soon; rather, it will serve as an initial reference for law enforcers, who would then need to contact an expert on the basis of KIKU’s findings for a detailed evaluation. But he adds that the more KIKU is used, the better it will become at identifying objects, thanks to the machine-learning technology.