We are experiencing an extended period of museum and gallery closures. Lockdowns intended to curtail the spread of the coronavirus mean it is ill-advised to linger among crowds of strangers in enclosed spaces—which counts out enjoying art in person. Some might consider this the death knell for museums and galleries, and from the perspective of visitor income, it certainly is catastrophic. But my hope is that virtual exhibits will remain an alternative art-going experience that will complement traditional in-person viewing when normalcy returns.

Just before the pandemic took hold last February, I was invited to speak at a conference in Ghent about the newly opened blockbuster exhibition, Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution. The exhibition brought together, for the first time, nearly every painting by Jan van Eyck, including the newly restored Ghent Altarpiece (the subject of one of my books, hence my involvement). The exhibition was a huge success, sold out months in advance, with plans to extend it. But then the pandemic struck, bringing any opportunity for in-person visits to an abrupt end.

A virtual tour of the Tomb of Pharaoh Ramses VI

Back home in isolation, I found myself taking virtual tours of cultural and historical places of interest –sometimes on YouTube, by way of a simple walkthrough, filmed and posted by a visitor with a decent camera; other times via official videos made by the institutions themselves. These often took the form of augmented reality tours, in which the visitor controls their pace while moving through the space, choosing which objects to explore and reading the occasional didactic pop-up—as in the virtual tour of the Tomb of Pharaoh Ramses VI. I found myself wishing there were more of these virtual tours, and of better quality, with more optional information for a deeper experience.

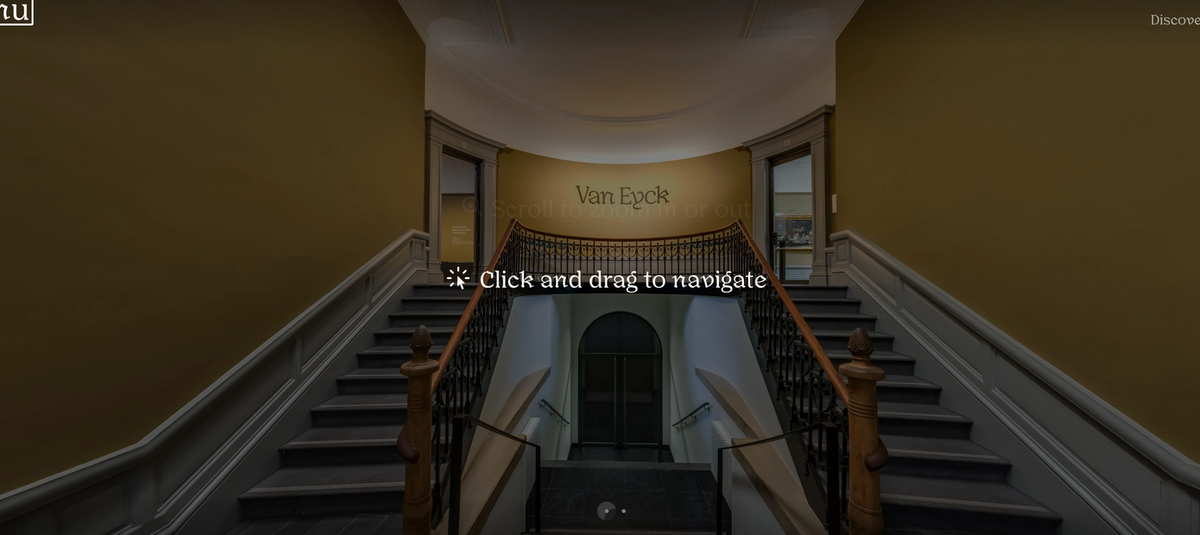

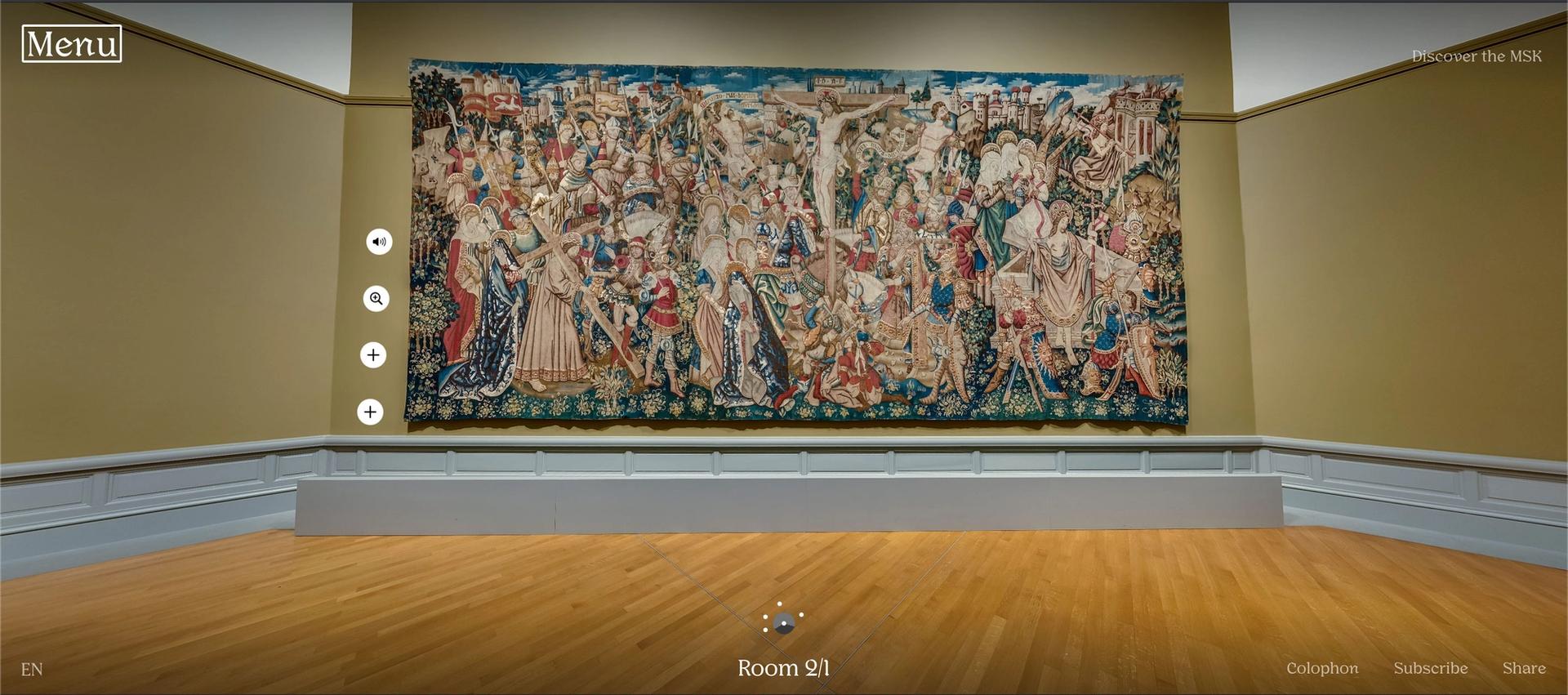

As if in answer to my wishes, the Van Eyck exhibition later released a 360-degree virtual tour featuring 120 artworks, divided in two: a version for adults and a version for children. Making virtual tours a standard accompaniment to both permanent collections and temporary exhibits would vastly increase the exposure of the institutions hosting them. This has been done with concerts and sporting events. Let it become standard for art shows, too.

Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution virtual exhibition

One might argue that access to virtual tours will result in fewer people attending art shows in person. If you’ve been to The Venetian in Las Vegas, who needs to fly to Venice, right? It doesn’t work that way. As Adam Gopnik recently argued in an article about the Louvre, the endless run of selfies, merchandise and images of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa have whetted appetites to see the painting in person, not acted as a stand-in for visiting it. A virtual tour doesn’t check off a box on a bucket list. The experience of art “in the flesh” is a level up from anything virtual—it is a sensory experience, deep and visceral. But engaging with art virtually is far preferable to not being able to engage with art at all.

Then there are exhibits made exclusively for virtual enjoyment. I recently curated one such exhibit, Missing Masterpieces, in collaboration with the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art (ARCA) and Samsung. Missing Masterpieces features 12 high-resolution images of lost paintings, by artists including Van Gogh and Monet—objects we could never visit in person, even if we wished to, because they were either stolen, mislaid, possibly buried with their owner, or even destroyed. The exhibition is available online for free, as well as to anyone with a Samsung The Frame TV. There is virtual wall copy for each painting, telling its story, and an interactive component—almost all of these works are out there somewhere and viewers are encouraged to write in with ideas about where they might be, or tips that might lead to their recovery. This sort of “impossible exhibition” can only really exist in the virtual sphere and therefore perfectly embraces the concept of it.

A billion pixel view of The Ghent Altarpiece

Perhaps the silver lining is in making standard a virtual accompaniment to the world’s collections and great exhibits, democratising who can see the art and learn from it. The art can be enjoyed by all, even if the experience won’t be as deep and primal, and it will prompt just as many people, if not more, to travel to see the exhibition in person.

Virtual experiences can advance scholarship where in-person visits cannot. When I wrote my book on The Ghent Altarpiece, I spent countless hours with it, in person, or examining photos of it in books. Yet I never noticed a particular figure within the painting, laughing maniacally, nor did I read about him in any of the previous books on what is arguably the most important painting ever made. That is, until I was able to examine a billion-pixel version of it. This allowed me to zoom in with such detail and clarity that I was able to spot this figure I’d never been able to see in person.

A virtual experience of high quality is not just second prize to being there in person, it may offer fresh revelations.