Awash in jewel-like hues and splashes of light, Jennifer Packer’s portraits of Black subjects have an auric quality. Like those photographs people have taken of themselves where the camera captures hazes of colours, supposedly energetic balances unseen by the naked eye, her paintings grasp at something just beyond the limits of accepted perception. Opening at London’s Serpentine Galleries this month, The eye is not satisfied with seeing is the Bronx-based artist’s first institutional solo show in Europe, featuring 35 works, from those made soon after she graduated in 2012 to canvases finished just a few weeks ago. It comes at a time when the world has been forced to bear witness to state violence, systemic racism and the weight of Black death in the US. But do the eyes really see? It is a question Packer comes back to again and again in her practice as she meditates on the power of grief and beauty and grapples with the limitations of paint.

The Art Newspaper: Your portraits, as much as they are of people you know—friends, family—are also abstractions. Similarly, as Christina Sharpe writes in her essay for your show at the Serpentine, you use “colour and light [to] transport us to a place beyond ordinary seeing”. This closely relates to the title of the show. Can you tell us what this phrase means to you and how it relates to your role as a painter of people?

Jennifer Packer: I’ve been thinking a lot about the nature of belief and how it impacts the ways that artists and artisans make objects, like the sort of thoroughness and fixation of devotion to the process and the practice. “The eyes are not satisfied with seeing” comes from a Biblical scripture. The whole quote is: “All things are full of weariness; a man cannot utter it; the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.” For me, the takeaway from that is that our senses are limited—there is always something beyond what we perceive and therefore you’re never really able to represent it fully. This relates to painting for me because when you’re painting someone, the subject gets wrapped up by the medium and its history but they also, of course, exist outside of that. So [painting] leaves space for… I want to say faith, but without it sounding too hokey. But what I mean by that is that there is an understanding that there are things that we don’t have access to, that exist around the things we make and things we do.

So you’re never really telling—and the viewer is never getting—the full story?

Yeah, a painting is like a quotation out of context. And it’s very clear sometimes when you go to a museum how poorly some things are quoted. I am inspired by the works of Michelangelo, El Greco or even painters like Philip Guston, Beauford Delaney, Palmer Hayden, Kerry James Marshall—I mean, God bless Kerry James Marshall, truly—but I think people are attaching too much importance to this idea of “rewriting the canon” [of Western art history]. It sounds good, but it’s still reactionary. I don’t fixate on that so much. I’m excited to know that what I’ve made has physically never been made before. That’s enough for me.

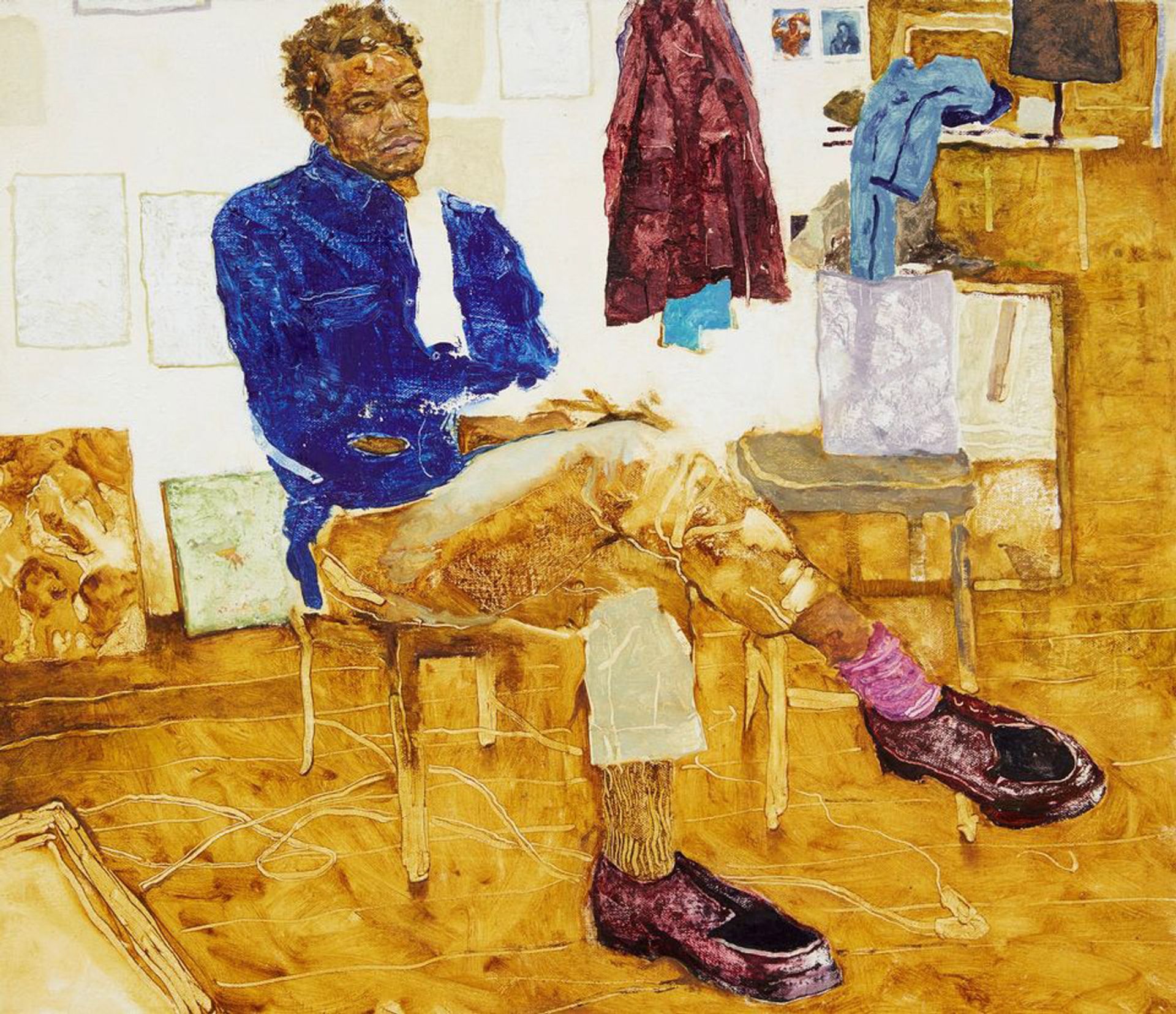

Packer’s Eric (2012-13), the subject sitting “in a room of things almost like satellites, floating around him” Photo: Jason Wyche; courtesy of the artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York

There’s a work in this show, The Body Has Memory (2018) that depicts a man in a hooded sweatshirt, and the sweatshirt itself becomes almost the dominant figure in the composition. Rizvana Bradley writes in her catalogue essay, the sweatshirt is a kind of metaphor that “can be regarded as a sartorial signifier of Blackness, in and as a singular vulnerability to racial violence, it also fashions a provisional shelter from a world that would otherwise consume and expel Black life at every turn”. In several paintings, clothing—I’m thinking of the excellent floral socks in Tia (2017)—or other items of note in the sitter’s periphery, really come to the fore. What about clothes or other external trappings becomes relevant for you as you paint these people?

I’m interested in signifiers and how they function historically, and the ways in which every little detail in a Renaissance painting had a place and had a meaning. Some signs contradict each other; they don’t always add up to a perfectly cohesive narrative. The trappings, as you called them, are not just beautiful decoration or distractions; I wanted them to have an equal presence, a power. That’s something I was thinking through in a lot of my earlier works and that I’m returning to now. There’s the painting Eric, from 2012-13, and he is sitting foregrounded in this room of things that are almost like satellites, floating around him. I thought about that work in making a lot of my new ones. There’s really no one way to read these items, though—I’m still figuring them out myself.

There is a lot of flora in your portraits, but you also paint bouquets on their own too, which become elegiac portraits in and of themselves. One of these is Say Her Name (2017), which is a reference to Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old Black woman who was found hanged in her jail cell after being assaulted and arrested by police. I remember speaking with you about it during a studio visit in 2017, and you noted how it is difficult to express grief over the loss of someone you didn’t know personally but with whom you still feel an intimacy. To what extent can grief, pain and suffering can be represented?

Sandra Bland’s death enrages me to this day. It’s easy to feel burdened by this desire for people to override the language of the painting or the subjectivity of the painter for something that ties it into culture and politics quickly, especially when it pertains to Black life. Look at how quickly museums like the Whitney [Museum of American Art in New York]have tried to collect protest art—so quick to historicise something, to put it in the past. That stops real change from happening in the now.

Now, three years later, the phrase “say her name” has a whole other meaning to it. Not a new meaning, as the issue remains the same—Black death at the hands of the state continues at an alarming rate and goes unchecked by the US’s current legislative powers—but awareness of the issue has reached a critical mass, as protests continue in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by police and the suspension of justice in the police shooting of Breonna Taylor. How has your relationship to these paintings or to your practice changed, if at all, as more people open their eyes to the systemic racial issues in the US and the list of names to say grows ever longer?

I feel really, really cynical about others opening their eyes. It’s like walking down the same street and seeing all the differently coloured doors but if someone asked you to name the colours you wouldn’t be able to even if you’ve seen them 1,000 times. Because you sort of refuse to know it or it’s not central to your everyday experience.

To oversimplify your metaphor, do you mean that white people are talking a lot about the need to preserve those doors but can’t recall the colours? I guess that goes back to this idea behind the show that the eye is not satisfied with seeing.

And back to the limitations of painting, too. I’ve been thinking about making a painting for Tamir Rice [the 12-year-old Black boy shot by police in Ohio when carrying a toy gun] for a long time, but the complexities of grief are too great. The flower paintings… they just feel too fraught after a while, I’ve had to stop making them. I don’t pretend that my paintings are doing some work in the world that isn’t already being done—and being done more effectively by other means.

Say Her Name (2017) references Sandra Bland, the Black woman who was found hanged in jail after being assaulted and arrested by police Photo: Matt Grubb ; courtesy of The Artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York

Biography

Born: 1984, Philadelphia

Lives: New York

Education: 2007, Tyler University School of Art at Temple University, Philadelphia; 2012, Yale University

Key shows: 2019 Whitney Biennial, New York; 2017 The Renaissance Society, Chicago. 2012 The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York

Represented by: Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York; Corvi-Mora, London

• Jennifer Packer: The eye is not satisfied with seeing, Serpentine Galleries, London, from 18 November; Jennifer Packer: Every Shut Eye Ain’t Sleep will open at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in early 2021 (dates to be confirmed)