The Dia Art Foundation in New York announced today that it plans to reopen its revamped Chelsea location sometime in April after a two-year $20m expansion and renovation that connects all three of its contiguous buildings in the neighbourhood with a united façade.

Admission will be free, and the inaugural exhibition features two newly commissioned installations by the artist Lucy Raven.

The 32,500 sq. ft project includes 20,000 sq. ft of exhibition and public programming space on West 22nd Street as well as the return of a bookstore while affording “a more cohesive visitor experience”, Dia says.

Jessica Morgan, the organisation’s director, said in an interview that the exact date remains uncertain but that Dia hopes to name one by the end of the month. She says she envisions the opening cementing Chelsea’s role as a centre for Dia, because the location “is so ineffable”.

While having dramatically evolved from when Dia opened in the neighbourhood in the 1990s, when the neighbourhood was “pretty barren” and populated mainly by industrial sites and garages, the art district remains nonetheless “incredibly important for us for its historic connections”, Morgan says. “It was a beacon.”

She says she hopes that the existing free admission policy, which extends to all five of the organisation’s New York City locations, “will encourage visitors to come to our spaces time and time again”.

The project uniting the three buildings was designed by Architecture Research Office. The firm is also at work on other physical elements of a broader $90m multiyear effort to advance Dia’s mission, program, resources and facilities, including the planned creation of Dia SoHo, a new 2,500-square-foot exhibition space on Wooster Street in Manhattan; the renovation of two installations nearby by the artist Walter De Maria, The Broken Kilometer (1979) and The New York Earth Room (1977); and the restoration and expansion of the lower level and surrounding landscape of Dia Beacon on the banks of the Hudson River in Beacon, New York.

As part of the Chelsea project, Dia says it has also extended Joseph Beuys’s Land Art work 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks) along West 22nd Street, bringing the total number of its paired basalt columns and trees to 38. “It seemed like a nice way to cement our relationship with that piece and its relationship with our space,” says Morgan.

A partial view of Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks) on West 22nd Street Bill Jacobson

Since its 1974 founding, Dia has strived to help artists realise visions that might not otherwise be achieved because of their ambitious scale. Many of the earlier works were mounted outside conventional galleries, like De Maria’s The Broken Kilometer and The New York Earth Room as well as his The Vertical Earth Kilometer (1977) in Kassel, Germany.

The two inaugural commissions by Raven are a film from this year, Ready Mix, and an installation of a brand-new version of works for her existing Casters series, which began in 2016. “Together these two projects address the formation and depiction of landscapes and civic spaces, particularly of the American West, and simultaneously propose abstraction as a tool for (re)perceiving these spaces,” Dia says.

Referring to Raven’s commissions, Morgan says, “I think we’ve always tried working with the curators on who are the artists we can make a difference with”–those who do not align “so easily with gallery representation for one reason or another and therefore need space and funding”.

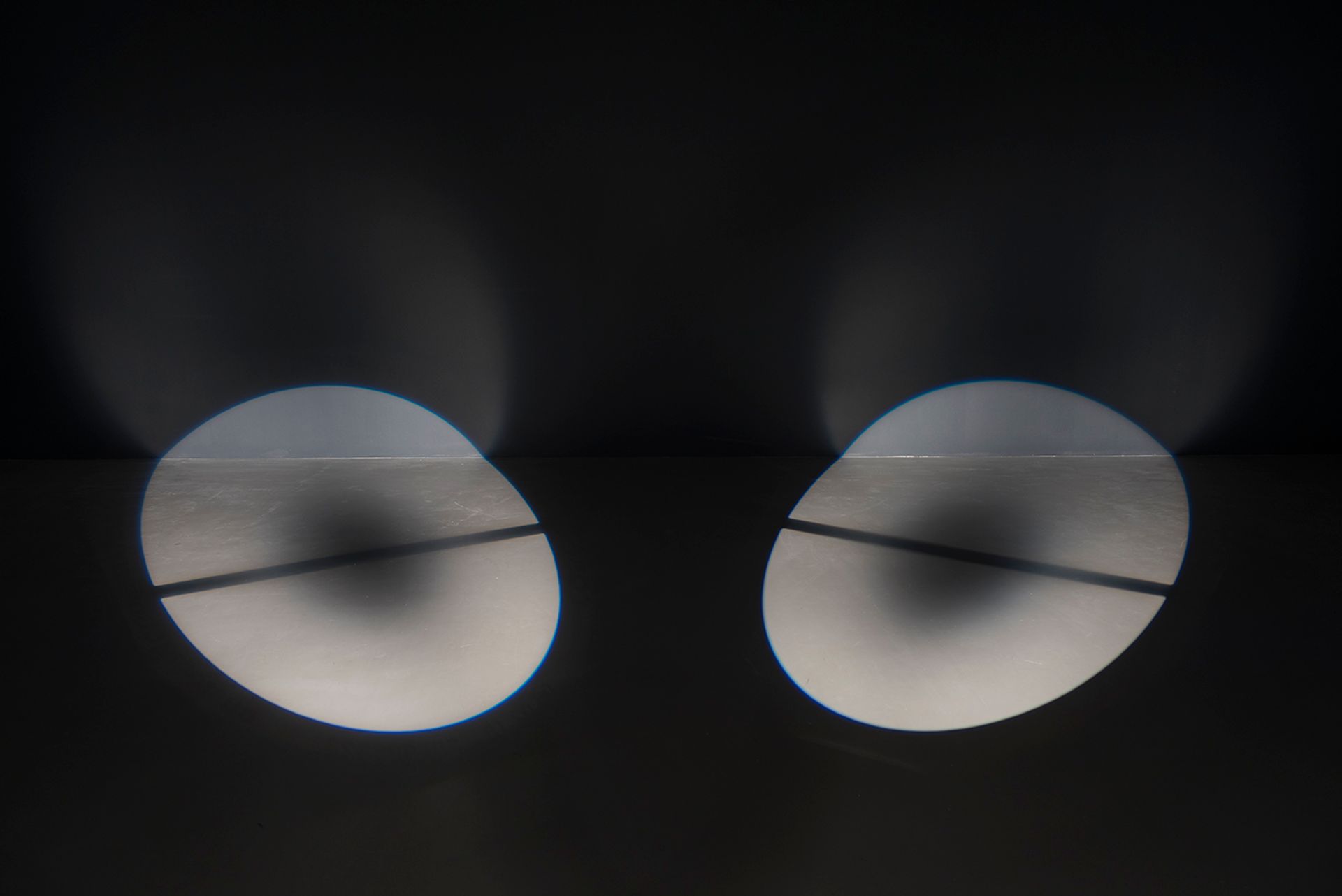

In the renovated East Gallery on West 22nd Street, visitors will view two pairs of moving light sculptures from Raven’s Casters series. As lights set in moving armatures move in and out of synchronisation with each other in paths encompassing over 360 degrees, Dia says, a choreography will emerge that illuminates the sculptures and the gallery.

Lucy Raven, Casters, 2016 © Lucy Raven; photo: Damian Griffiths; courtesy of the artist

Raven’s film, meanwhile, shot at a concrete plant in central Idaho, is in black and white and lasts around 50 minutes. The artist records the transformation of minerals and binders into ready-made concrete in the work.

Ready Mix “contends with the myth perpetuated by traditional westerns of the so-called frontier—a receding, seemingly empty, and untamed landscape—by collapsing its perspectives of distance into visual flatness and material density,” Dia says. The artist’s installations will remain on view through January 2022.

Morgan says that Dia has so far received $80m of the hoped-for $90m in its fundraising campaign. The majority of the funds will go towards building Dia’s endowment, “and I hope it will help enormously in the future,” she adds.

Amid myriad Dia projects, the planned new SoHo location presents a challenge, she notes. “SoHo has gone through this massive downturn, and now almost every store has shut,” she says of a former artists’ neighbourhood that later evolved into a shopping mecca. “But SoHo was where we began. How can we bring this presence back? It will be fascinating to see.”

Dia, which has faced financial setbacks over the years, says it is also labouring to bolster its supporting operations across its museums and artists’ installations in New York State, Utah, New Mexico and Germany, among them Dia Beacon; the two installations in SoHo by De Maria; Dia Bridgehampton on Long Island; De Maria’s The Lightning Field in western New Mexico; Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels in Utah; and De Maria’s The Vertical Earth Kilometer in Germany.

Dia Beacon attracts the most visitors among the sites: 350 to 360 people a day on weekdays, Morgan says, just one-third of the number it drew before the coronavirus pandemic hit. Pre-pandemic, the number rose to 1,600 on weekends.