Buying with your ears. That’s the phrase art-world insiders use to describe the way some newbie collectors slavishly acquire works by names everyone else is talking about at any given moment in the cultural fashion cycle.

“Serious” collectors, on the other hand (so the long-received wisdom tells us), spend years developing an eye that can unfailingly distinguish the enduring from the fad, resulting in homes filled with art exemplifying some kind of museum-validated canon—one largely determined by white men.

At least, that was the theory. But how does that square with the realities of today’s collecting culture, in which art, more than ever, is used as a speculative asset to be flipped, hedged or hoarded? And how can we cling on to the notion of a fixed “canon”, when validators like the Baltimore Museum of Art want to sell off masterpieces by canonical names such as Clyfford Still and Andy Warhol to buy pieces by living Black and female artists?

“The definition of the collecting culture has changed,” says John Zarobell, an associate professor at the University of San Francisco and author of the 2017 study, Art and the Global Economy.

“The relationship between the canon and the collecting culture has now shifted,” Zarobell says. “It has moved to contemporary art. The value is driven more by external factors, as well as market actors, than by art history.”

The art market has expanded massively over the past 15 years or so. International auction sales, according to Rachel Pownall of Maastricht University, increased from $2.8bn in 2003 to $21.5bn in 2014, buoyed by globalisation, soaring returns on capital for the wealthy and perceptions that contemporary art was a lucrative, status-enhancing investment.

The market has cooled since then, even before Covid-19 closed down live auctions, fairs and exhibitions. But the finance-driven dynamics remain in place. Essentially, buyers are betting on either red or blue, speculating short term on a hot early-career “future” or investing long term in an established blue-chip name.

Now, in the absence of big-name trophies selling for more than $100m at live auctions, it is hot emerging artists, particularly if they are Black and/or female, who generate most of the noise in the market—and the media that cover it.

Luncheon on the grass, a recurring dream (2020) by Jenna Gribbon, an emerging artist who was the focus of attention during September’s Gallery Weekend Berlin Ludger Paffrath; ©Jenna Gribbon, courtesy GNYP Gallery

Berlin-based dealer and adviser Marta Gnyp’s sell-out exhibition of new paintings by New York-based artist Jenna Gribbon was one of the most talked-about shows during Gallery Weekend Berlin in September. “It’s exactly what the market wants today: an emerging artist concentrating on themes of identity politics,” she says. “I have 330 people wanting her work.”

Art-world insiders were queuing up to acquire these painterly, politically aware images of Gribbon’s musician girlfriend and other loved ones, priced between $7,500 and $25,000.

Artists like Gribbon, whose works are selling out in galleries but have yet to make a noise at public auctions, are the sort of future that every ear-to-the-ground collector and speculator is looking for. Recent sell-out shows in London of paintings by the Black British artist Jadé Fadojutimi at Pippy Houldsworth and by Ghana-based Kwesi Botchway at the Accra-born Gallery 1957’s London launch show in October represent similar primary market hot-spots.

With hundreds of would-be buyers at the bottom of waiting lists, by the time desirable works by hot names do eventually appear on the auction market, prices can escalate, inflating the value of works owned by those lucky enough to be at the front of the queue.

In July, Bloomberg revealed that the former Sotheby’s executive Allan Schwartzman had been the seller of a landscape by the Canadian painter Matthew Wong (who died by suicide last year) that had sold at Sotheby’s the previous month for $1.8m. Shwartzman had bought the work two years earlier at a New York gallery show for $22,000. More recently, Artnet News chronicled how, at Phillips in February, the Ghanaian wunderkind Amoako Boafo used proxies to bid a 20-times-estimate £675,000 for one of his own paintings that was being flipped by the Los Angeles-based speculator Stefan Simchowitz.

Feeding frenzy

With this feeding frenzy for futures going on, whatever happened to “serious” collecting? Or was that just a connoisseurial myth anyway?

“I don’t think the motivations for collecting have changed that much over time,” says the Venezuelan-born, Monaco-based collector Tiqui Atencio who in 2013 sold Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Dustheads (1982) at Christie’s for a record $48.8m. “Love of art isn’t necessarily the first instigator—politics, social improvement and financial advancement have always existed,” Atencio says, pointing out how, in the 18th century, Catherine the Great collected Old Masters to improve her image.

Atencio is the author of the recently published book, For Art’s Sake, which gives us private tours of the homes and collections of 24 of the world’s leading contemporary art dealers. But even an experienced collector like Atencio is not averse to a little buying with her ears. “If the works are being bought by other collectors and collected by museums, then I’ll go for it, no matter what,” she says.

It’s difficult to escape the conclusion that, in today’s art world, high value (or perhaps just high price) is more often than not determined by crowd appeal rather than a considered critical consensus.

“The canon has become a device of the market,” Zarobell says. “The value of art has become less about the discourse of aesthetics, but more about the buzz.”

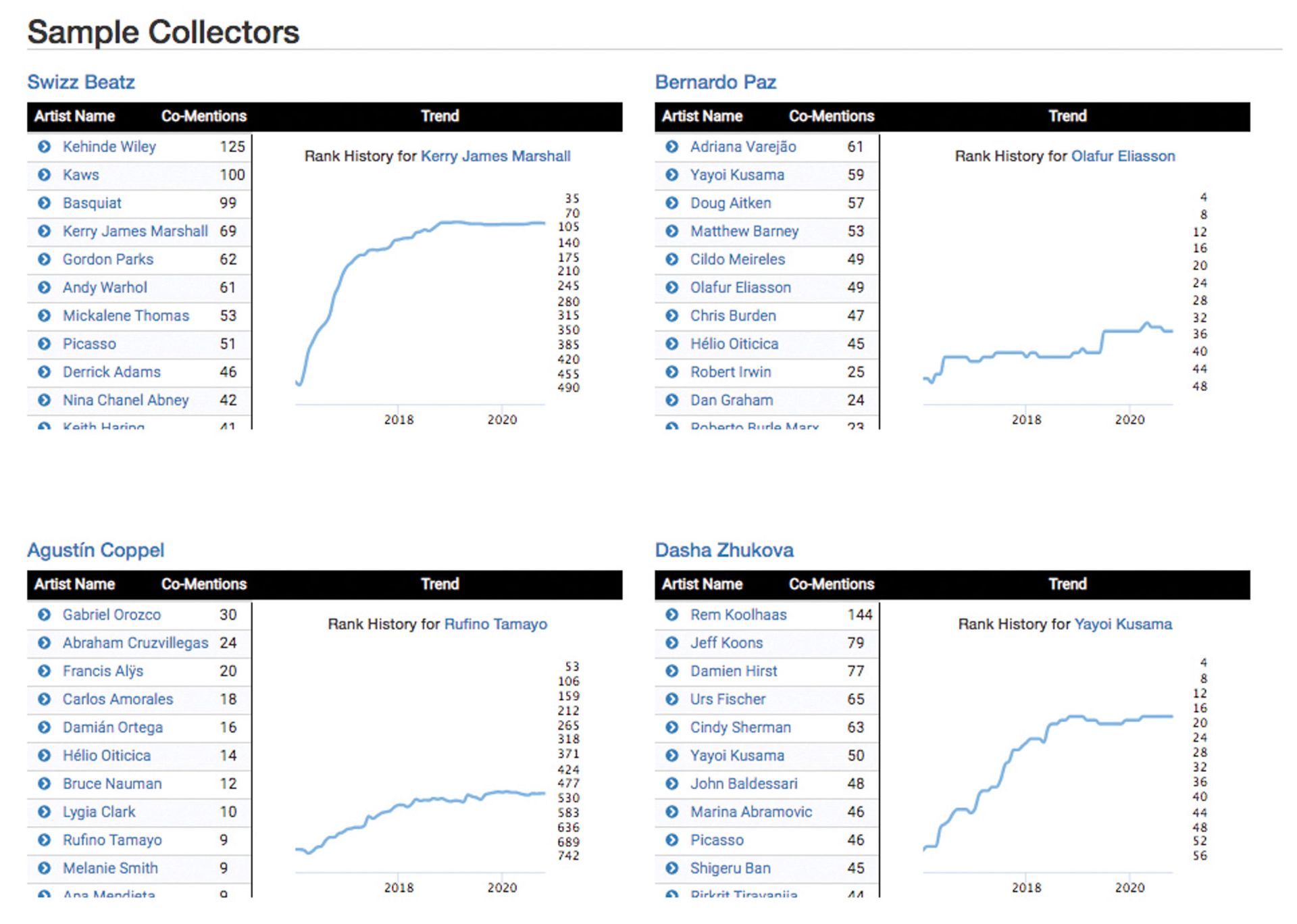

Phillips is partnering with Articker, a data platform that trawls through more than 60,000 publications to track daily media coverage for artists, from Leonardo to Banksy Paffrath; ©Jenna Gribbon, courtesy GNYP Gallery. Articker: Courtesy of Phillips and Articker

And now buyers have an algorithmic tool that actually measures the buzziness of the art that’s around. In August, Phillips auction house announced a partnership with Articker, a “data-driven research feature” that, according to the auction house, is “set to transform art business intelligence.”

The Articker feature continually scours more than 60,000 publications to track who are the most written-about artists of the moment, then ranks them in real time by media coverage, giving daily bulletins. At the last count, Pablo Picasso came out top, followed by Andy Warhol, Banksy, Van Gogh and Leonardo da Vinci, which, coincidentally, might be a lot of people’s idea of a sensible artistic canon, if not E.H. Gombrich’s. Damien Hirst, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jeff Koons come in at eight, nine and ten.

“It’s making our specialists better, creating a bigger context,” says Jean-Paul Engelen, a deputy chairman of Phillips, of Articker.

But won’t this algorithmic tracking of media and market darlingdom just encourage even more collectors to buy with their ears? “Like all technology, it’s extremely useful, but can be abused,” Engelen says. “It comes with responsibilities for us.”

Meanwhile, as the art historically minded try to get their heads around $1m Banksy prints making more at auction than any engraving by Albrecht Dürer, the Covid-19 pandemic has at least allowed a whole new audience to buy with their eyes at a much more approachable price level.

Survival mechanism

Launched on Instagram in March, the Artist Support Pledge is a non-profit initiative devised by the UK-based painter Matthew Burrows as a survival mechanism for colleagues impoverished by lockdown. Artists are encouraged to post images of works for sale, priced at up to just £200. Those whose sales reach £1,000 then pledge £200 to buy work from other artists, thereby setting up a mutually supportive network.

To date, #artistsupportpledge has generated nearly half a million tagged posts and 69,300 followers around the world. Tens of thousands of artists are now making a living, thanks to the campaign. Among them is Danish-based David Risley, who ran his own contemporary art gallery, first in London and then in Copenhagen, from 2000 to 2018. Recalling his time as an art dealer, Risley says his main mistake was to think he was selling paintings.

“People weren’t buying paintings. They were buying futures, potential, status, access, a social life. Mainly they were buying money, or the potential of money,” Risley says. “I often heard of collectors buying works with no intention of seeing them, let alone living with them. The work was bought solely with the intention of going straight to storage, to sit and accrue value until resale.”

Now, Risley is steadily selling his own paintings through Instagram to people who, well, just like the look of them. “I make enough to pay the rent,” Risley says. “It’s great.”

Artist Support Pledge’s innumerable thousands of £200 sales might not trouble the algorithmaticians (yes, that is a real word) at Articker or Artnet. But they are, in their own quiet way, invigorating a grassroots collecting culture that has been overshadowed by a financially supercharged art market divorced from most people’s economic realities.

There are still collectors out there who seriously like art. It’s just that they’re the ones spending £200, not £200m. And what they buy won’t reach your ears.