The 13th Gwangju Biennale, one of Asia’s most important contemporary art exhibitions, is scheduled to take place early next year against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic. Sixty-nine artists are due to participate and 41 new commissions will be unveiled in Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning (1 April–9 May, subject to Covid-19 restrictions). We asked the artistic directors, Defne Ayas and Natasha Ginwala, about working in the shadow of coronavirus, queer desire in a Korean context and why including a Mongolian artist matters.

The Art Newspaper: How has the pandemic affected your curatorial schedule and planning?

Defne Ayas: We are building on the two artist research trips we organised to Korea last year. We’ve about 40 new commissions in production. Those artists who joined us on the trips have benefitted immensely because those commissions really are coming together, although three were halted and have since resumed.

Natasha Ginwala: Our last [research] trip was in January, this was the final moment for all of us to build on local research before this apocalyptic time. As soon as the pandemic hit, it was not possible for artists to do the production in the way they had planned and proposed. If we had not had this window, then in a sense we would have had to dramatically shrink new productions. This postponement window—around May—helped artists feel confident about producing work.

DA: Suddenly shipping prices tripled; we couldn’t make contact with shipping companies in some countries. Shipping details of new commissions came through in a clearer way during this time. We were also in dialogue with our peers globally, watching what Yokohama triennial and the Berlin biennial were doing. The time that we gained allowed us to really zoom in. Also, it’s a first-world experience there; Korea has initiated an effective contact tracing and surveillance system.

You’re confident that local audiences will attend?

NG: There will be a huge local audience, Gwangju has this history of violent rupture—Leftist resistance and a civic mission that accompanies the cultural mandate. There has always been a commitment to local audiences, that’s important for us with or without the pandemic.

DA: A more local turn is inevitable. Also, the ecology of Korea has demand for art. We also gained some audiences when we mobilised our public programmes online; they were supposed to take place in May at the 40th anniversary of the uprising.

Candice Lin will be participating in this year's biennial. Shown here: installation view, of A Hard White Body, a Soft White Worm, Portikus, Frankfurt, (2018) Courtesy of the artist

Mutability, hybridity, the fluidity of interdisciplinary artistic practices—these seem to be underpinning concepts for the biennial. Is this correct?

NG: It’s a question of intelligence really, and what forms of intelligence are seen as the dominant forms—this may be technocratic or heteronormative. It’s about the quality of intelligences that have been oppressed whether that’s feminist, ancestral, indigenous and mind-body relations. It’s about not avowing the binary—it’s actually like seeing these worlds operate together and in conjunction. And in Korea, that’s very much the reality.

DA: In Korea, you have hyper-capitalism, you have discussions around gender issues, around race. Everything is so condensed in a very 21st-century way, yet you also have multiple centuries pushing back and forth. For instance, John Gerrard’s installation works with 21st-century neural networks, yet he is reviving folk figures in a processional dance. Our artists are not only invested in new media practices today, but also an interest in ancestral knowledge, which may bring heterogeneity to an understanding of augmented intelligence at play in the world today.

What makes it so compelling is the atmosphere of South Korea; the biennial has a political agenda because of the Gwangju Uprising, this mother of all uprisings that took place in 1980 opening the way to the country’s democratisation. The biennial sparks discussion about this traumatic experience every two years.

NG: The idea is to work on a publication that looks at feminist practices and voices; the book Stronger than Bone that we have produced was a way to respond to these younger voices in Korean feminism. There is an entire floor [in the biennial] about the intersection between militarism, queer desire and the hybridity of pleasure beyond disciplinary logic. There is deep violence towards the queer community and issues around surveillance and sexual violence.

DA: The Yangnim mountain [where the biennial venue and community art space Horanggasy Artpolygon is located] was a site for sky burials taken over by Japanese colonial forces and American missionaries. It has complex histories. One of the reasons the queer discussion may never have been addressed is because of these evangelical forces at play.

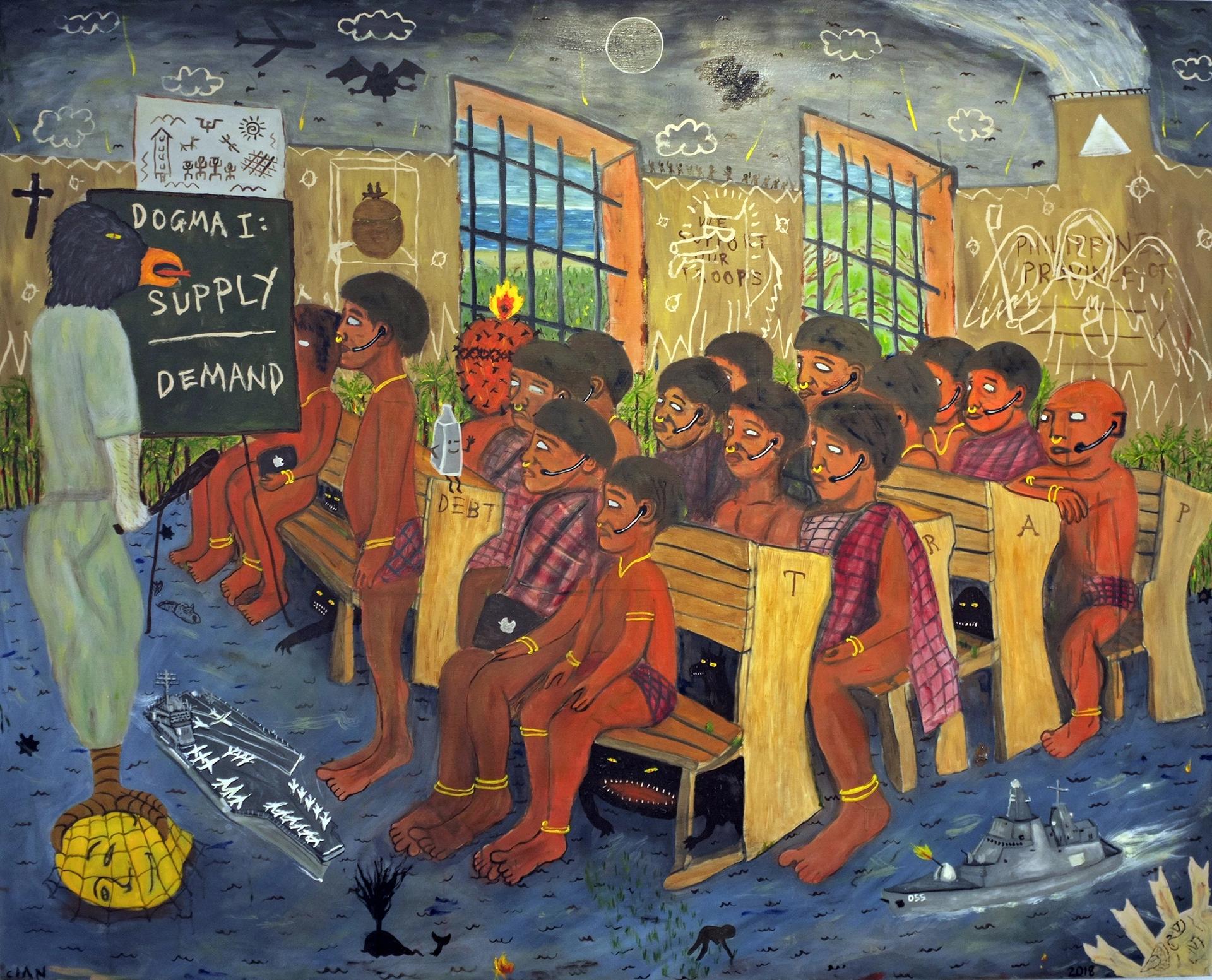

Cian Dayrit's A Rare Colorized Image of Institutional Assimilation (2018) Courtesy of the artist

There’s also a focus on Korean shamanism in the exhibition—what kind of perspective do you take on this ancient practice?

NG: It is really important that Korean shamanism is not looked at as a kind of antiquated fetish. It is very contemporary as a practice. It is not completely separate from the cultural domain and there are also practitioners who say shamans need to be understood also as Korean indigenous practitioners.

DA: Shamanism is also a filter for looking at class divide and gender issues, and what has been ostracised.

The artist roster includes Cian Dayrit from the Philippines, Korean artists Sangho Lee and Moon Kyungwon, and Los Angeles-based Candice Lin. Can you elaborate on the artist mix?

NG: While Gwangju has been very important to the largely contemporary art conversation, we have invited artists from several parts of Asia for the first time, for instance, there’s never been a Mongolian artist in the Gwangju Biennale despite the fact that Mongolia has a strong presence in the local Korean economy [Tuguldur Yondonjamts, who was born in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, is participating].

DA: What the selected artists have in common is investment in social justice, environmental justice. It is at the core of their existence.

UPDATE: This article was updated on 2 February 2021 to reflect the postponement of the Gwangju Biennale.