Absinthe and wine has often been blamed for exacerbating Vincent van Gogh’s medical and psychological problems, but last week a study by eminent specialists suggested that the withdrawal of alcohol may have caused some of his mental crises.

Under the headline “Van Gogh likely to have suffered twice from delirium caused by alcohol withdrawal”, the University Medical Center Groningen, in the northern Netherlands, sprung the surprise. The experts say this is the first time it has been argued that some of the artist’s crises were caused by a lack of alcohol.

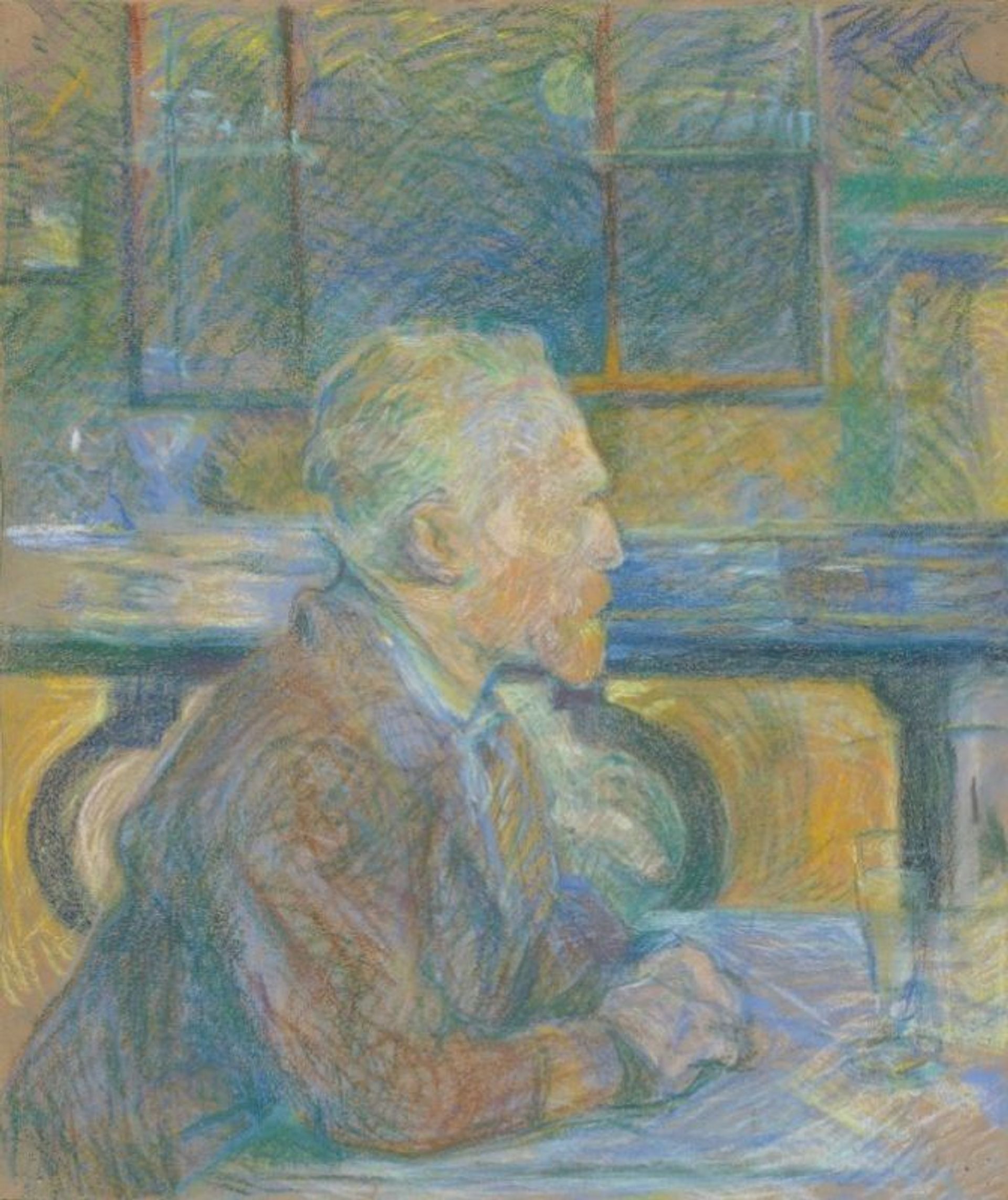

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Portrait of Vincent van Gogh (1887) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

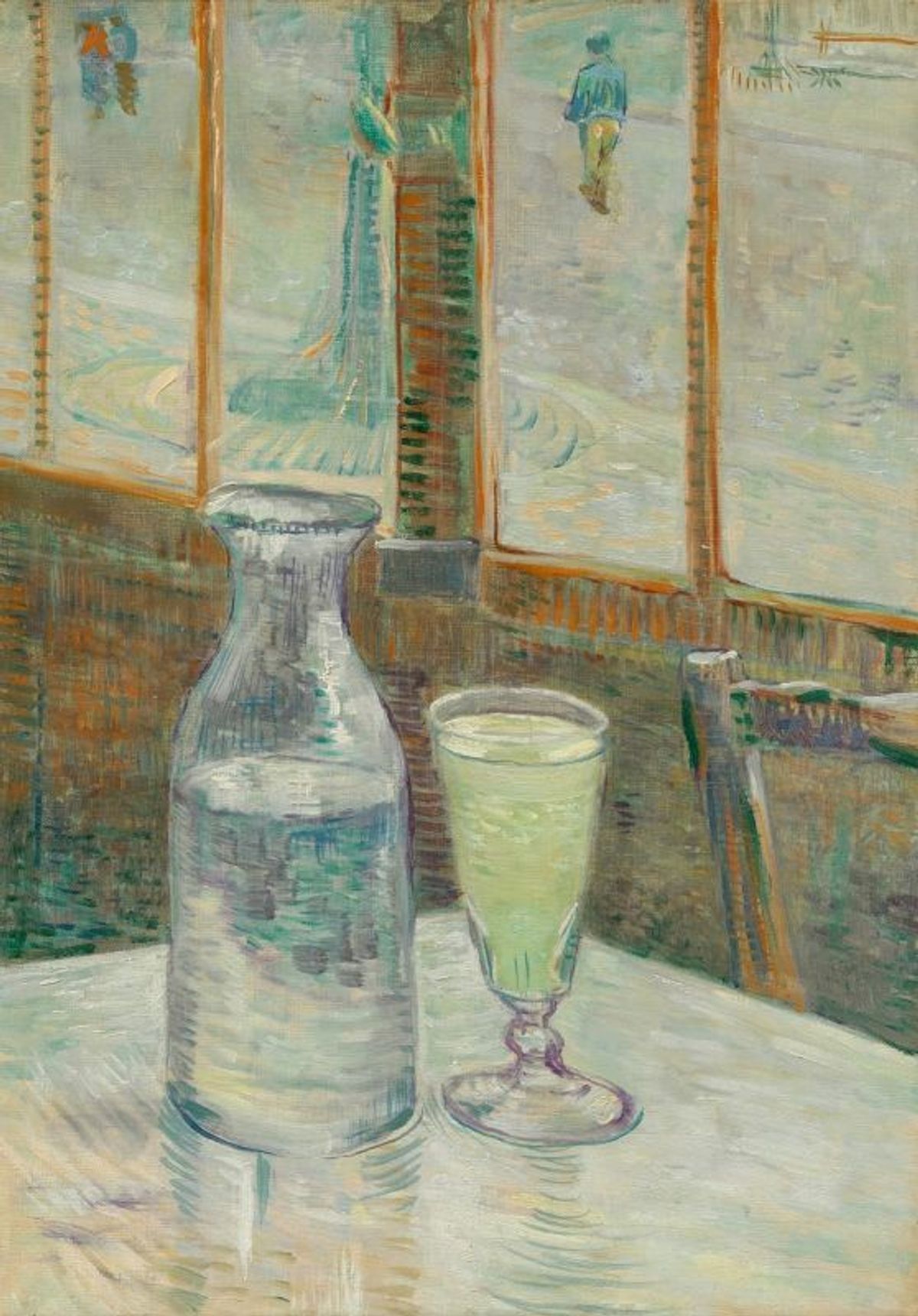

While living in Paris in 1886-88 Vincent drank considerably in the bars of Montmartre, probably both absinthe and wine. After his departure he wrote to his brother Theo to say that he had become “almost an alcoholic as a result of overdoing it”. In Arles, in Provence, he seems to have cut down on drinking, but still enjoyed wine with his meals.

The Groningen paper, just published in the International Journal of Bipolar Disorders (Springer Open), was written by four eminent specialists: Willem Nolen, Erwin van Meekeren, Piet Voskuil and Willem van Tilburg.

They argue that Van Gogh suffered a delirium (sudden confusion) during at least two periods, “due to alcohol withdrawal, because he was forced to suddenly stop drinking alcohol following his admission to hospital after the ear incident”. He was first hospitalised from 24 December 1888 to 7 January 1889 and, after a setback, he returned to hospital from 7 to 17 February 1889.

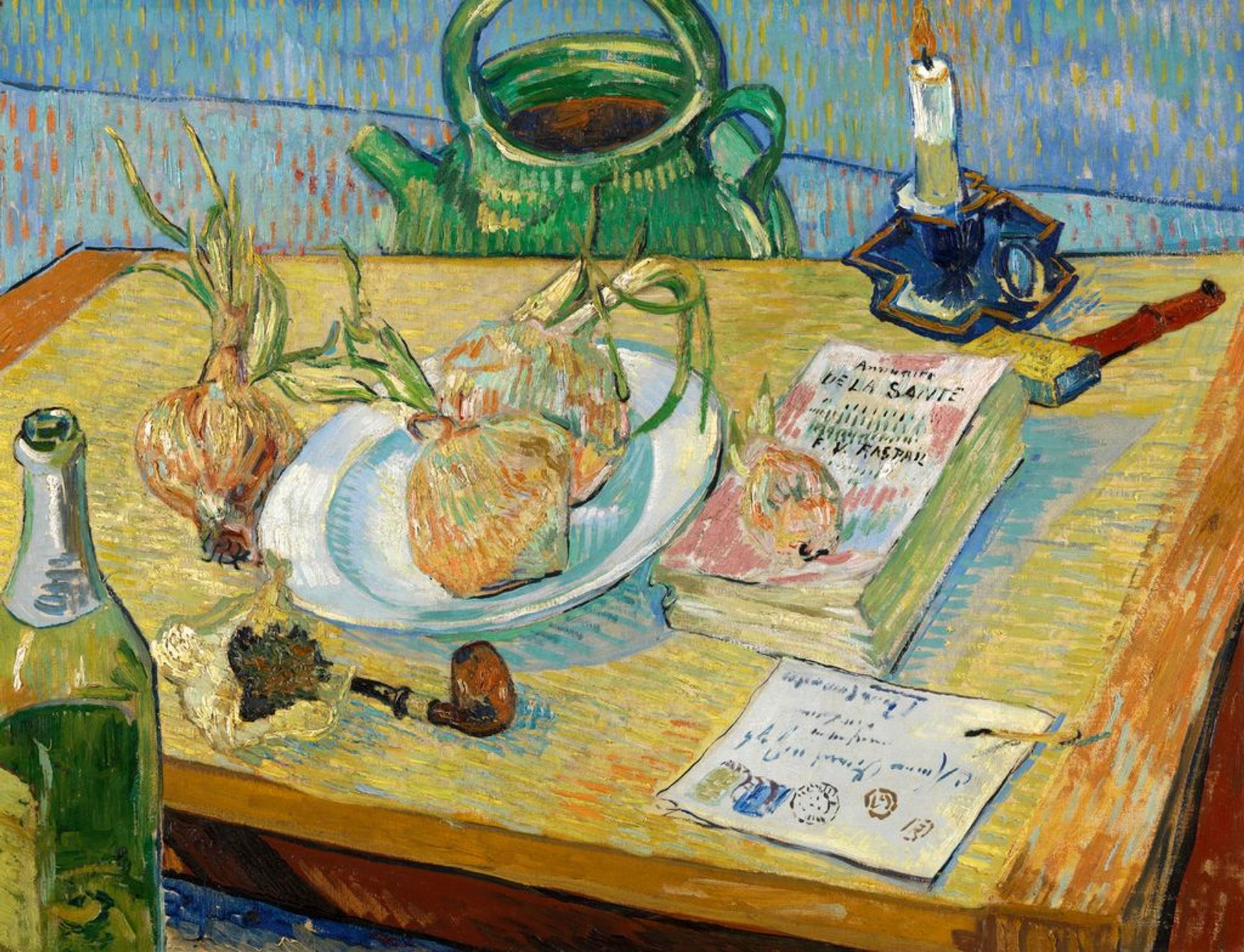

In late January 1889, between these two periods of hospitalisation when he had presumably been deprived of alcohol, he painted a still life with personal objects from his home, the Yellow House. At the front of the painting is an opened bottle, which appears to be empty. Although its symbolism is not entirely clear, the bottle may well represent a welcome sign of normality after his return from hospital.

Vincent van Gogh’s Still Life (1889) Courtesy of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

The experts go on to argue that when the artist moved to an asylum he was “forced to minimise or even stop drinking”. Their study is therefore based on the assumption that Van Gogh drank virtually no alcohol during his year at the asylum, but I would argue this is not correct: he was allowed double the quantity of wine normally provided for inmates.

When Vincent had been considering whether to enter the asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence he asked his brother Theo if he could have “a little more wine than usual down there, half a litre instead of a quarter [a day]”.

In Theo’s subsequent letter to the asylum doctor, he made two special requests: Vincent “should be at liberty to paint outside the establishment” and “have at least half a litre of wine with his meals”. In modern parlance, this represents 42 UK units of alcohol a week—three times the current recommended maximum.

Although it may come as a surprise, wine was generously served at French asylums. An 1874 government survey of all French asylums recorded that male patients typically received between 14 and 40 centilitres of wine a day, not quite as much as Van Gogh’s 50 centilitres, but still quite significant.

It is true that Vincent wrote to Theo that since his arrival at the asylum he had maintained “absolute sobriety in eating, drinking, smoking”, but that does not mean abstinence. It means that he did not get tipsy, although it does not rule out having a substantial glass of wine with lunch and supper. Vincent may also have meant that he was keeping off spirits, since wine was so widely drunk that it would hardly be remarked on. The bottom line is that he probably drank half a litre of wine a day during periods when he was relatively healthy.

Focussing on the conclusions of the Groningen study, the four authors argue that Van Gogh suffered from comorbid illnesses (more than one disease or condition).

They conclude that “he likely developed a (probably bipolar) mood disorder in combination with (traits of) a borderline personality disorder”. This was “worsened through an alcohol use disorder combined with malnutrition, which then led, in combination with rising psychosocial tensions, to a crisis in which he cut off his ear”.

Following the ear mutilation he “developed two deliriums probably related to alcohol withdrawal”, in late December 1888 and earlyFebruary 1889 at the hospital in Arles. The authors argue that it is likely that at least the first brief psychosis in Arles in the days after the ear incident, when he stopped drinking abruptly, “was actually an alcohol withdrawal delirium”. This was followed by a series of “severe depressive episodes”, eventually leading to his suicide in July 1890.

Since Van Gogh’s death many hundreds of medical articles have been published on his condition, proposing a wide variety of theories. Four years ago the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam held an exhibition and a symposium entitled On the Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and his Illness, in an attempt to work towards a better understanding of the issues.

The museum promised a publication with the findings of the specialists who contributed to the symposium, but since then it has proved difficult to reach agreement on a text and nothing has yet appeared. Voskuil, one of the Groningen authors, admits that discussions have “not resulted in enough consensus to express final conclusions”.

Four of the 14 medical specialists involved in the Amsterdam symposium have now gone it alone, putting their own views in print in the Groningen study. But as the lead author Nolen admits, “our article certainly won’t be the last on Van Gogh’s illnesses”.

Art historians at the Van Gogh Museum have become increasingly aware that the medical diagnosis of historical figures is full of pitfalls. However, they hope that the report promised at the 2016 symposium will eventually be published, either next year or in 2022.