Asked to describe himself in ten words in 2001, Terence Conran came up with “ambitious, mean, kind, greedy, frustrated, emotional, tiresome, intolerant, shy, fat”. He was right to put ambition first amongst these traits. His relentless drive to create, innovate and improve directed the fugitive stuff of British taste in food, interiors and buildings, from the terracotta chicken bricks now relegated to the back of cupboards to the continental quilts as ubiquitous as the low-slung Modernism of living rooms and olive oil and garlic-flavoured cuisine. Messianic, sybaritic, four times married, with a charm that could switch off as well as on, Conran rose in tune with the nascent grooviness of the Swinging Sixties when Britain—and particularly London—became cool.

With his contemporaries Tony Snowdon, Mary Quant and Elizabeth David, Conran envisaged new possibilities for Britain’s dreary post-austerity landscape of rationing, utility and make-do-and-mend. It remains hard to say whether his achievements were steered by the zeitgeist or drove it: Habitat, most famous of the brands he invented, was succeeded by the slicker 1970s Conran Shop, his first café venture —a glorified soup kitchen—morphed into the 90s party palace of Quaglino’s. His obsession with the design of things began with doll’s house furniture made and sold to a local toyshop during a bout of childhood appendicitis and climaxed with the Design Museum.

Lifestyle was a word he shied away from, but he had a missionary zeal for the aesthetics and utility of everyday objects in the idealistic traditions of both William Morris and the Bauhaus. In The House Book (1974) he warned parents that policing their children’s choice of toys would not mean that they would grow up with faultless taste of their own, because, “they’re that much more likely to rebel against yours”. But his children Sebastian, Jasper, Ned, Tom and Sophie have made their names and livings in the worlds of art, design and lifestyle too.

Born into a middle-class household in suburban Surrey to a businessman father and a more artistically inclined mother, Conran was educated at Bryanston in Dorset. Here he excelled in arts and crafts—his pots made in the classes of Donald Potter, acolyte of Eric Gill, were exhibited at Heal’s—but flunked games and left in “irregular” circumstances. Next, at the Central School of Art and Design in London he studied textile design and began a lifelong friendship with the sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi, but again quit before graduation.

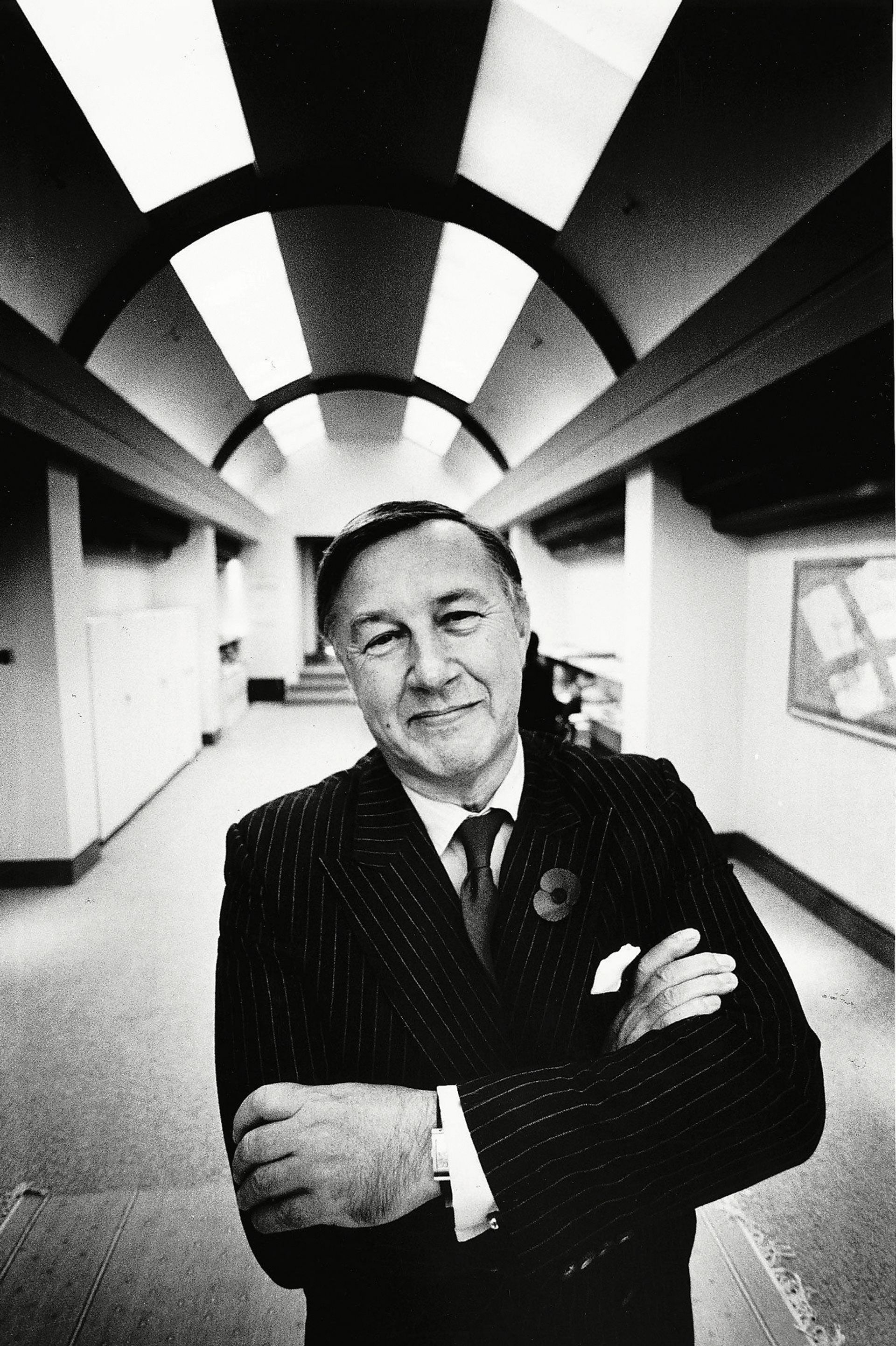

Conran in 1987, the year he bought the Michelin Building in Fulham Road, west London, home to the Conran Shop and Bibendum Shutterstock

By 1951 he had obtained his first job at the Festival of Britain under its effervescent director, Hugh Casson. But designers were still an unrecognised tribe then, designated “industrial artists”. And so, in sheer frustration he set himself up in a workshop in Bethnal Green with Paolozzi, making welded Bauhaus-style steel-legged coffee tables and basket chairs, now highly prized by collectors.

Grand gourmand

Food would be equally important to him. Aged 21, Conran made his first gastronomic trip to France, working as a kitchen skivvy in a Paris restaurant, amazed to find a country that had “never heard of rationing”. Francophilia became key to the Englishman’s version of France that he artfully marketed ever after. In 1953 he made his first venture into catering. The Soup Kitchen in Charing Cross served only soup, French bread, cheese, real coffee and apple tart. His first customers were tramps mistaking this for a charity canteen, but a passing journalist branded it as the trendy place to be. Two years later he met and married his second wife, Shirley Pearce, who was waitressing in his new restaurant the Orrery (a first marriage to Brenda Davison, an architect, lasted just a few months). With her nose for publicity she persuaded her reluctant husband to pose with her for the weekend supplements, dining elegantly amongst his spindly modern furniture in their flat in Regent’s Park Terrace. Branding became key to Conran’s achievements and he founded the Conran Design Group the following year.

Dissatisfied by poor sales of the furniture he had begun manufacturing in his new factory in Thetford, Norfolk, Conran decided to go into sales himself. The result was the first Habitat store, which opened in 1964 in the then unfashionable Fulham Road, west London. Caroline Herbert, a food writer who became his third wife in 1963, contributed much to its success, producing its first catalogue in the form of a folded sheet of brown paper. Here the utility of Bauhaus and the folksy peasant aesthetic of Provence blended in consignments of Polish enamel, tubular chairs, French crockery and basketware stacked in abundance on floors and tables to give that “irresistible feeling of plenty you find on market stalls”.

Conran wanted his customers to brush up against the furniture like cows, until they got used to it. Despite rolling power cuts and Christmas shopping lit by Camping Gaz, consumers flocked in. Elizabeth David sourced products for her own shop, while George Harrison, Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton and Kingsley Amis hung out there. Habitat even sold affordable art, commissioning prints by David Hockney, Peter Blake and Robyn Denny, but also cheap pasta storage jars, offered for sale just as the market for dried pasta took off in the UK. Conran’s brand expanded with a growing middle class and Habitat stores in Paris and New York followed.

The 1980s and 90s were a time of boom and bust, with developments such as Bibendum in 1987, marrying high-end home store and restaurant gastronomique, and the acquisition, restoration and revival of unusual old buildings. The flotation of Habitat, acquisition of Heal’s, Mothercare and Next and merger with British Home Stores (BHS) created the enormous business Storehouse, ending with disaster when Conran’s individualistic business model became over-stretched. Conran was no longer in control and aghast at the quality of its merchandise, denouncing a frilly pink dressing gown that was one of BHS’s best sellers as “pure Coronation Street”. But he was resurgent, buying back the Conran Shops, creating a new breed of modern British restaurants and helping his brother-in-law Antonio Carluccio to propel his eponymous restaurants into a successful chain.

Lifestyle was a word he shied away from, but he had a missionary zeal for the aesthetics and utility of everyday objects in the idealistic traditions of both William Morris and the Bauhaus

Conran’s clouds had silver linings: the 1980s flotation of Habitat enabled him to found and fund the Conran Foundation, the educational charity that brought the Boilerhouse project to the basement of Sir Roy Strong’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 1981, with the design historian Stephen Bayley—playing Robin to his Batman, as one insider quipped—at its helm. Conran believed that Britain had lost sight of what design should be: 25 successful and didactic exhibitions followed. The last and most popular was on the Coca-Cola brand, provoking an uprising of curators and their eviction from the museum. Conran suggested that with his languid moustache and floppy-lapelled suits, Strong should be stuffed himself and preserved behind glass in his own museum as a valuable period piece. His masterpiece project transferred to the Design Museum at Shad Thames, where the nondescript hulk of a 1940s banana warehouse metamorphosed into a large, self-confident and plausible building in the Bauhaus’s International Modernist style of the 1930s. Under Stephen Bayley, Alice Rawsthorn and Deyan Sudjic its exhibitions and displays brought design into the cultural landscape of Britain, supported by Margaret Thatcher with a rather stiff reception at Downing Street. A further gift of £17.5 million moved the museum to the site of the Commonwealth Institute on High Street Kensington in 2016.

With his restless character and low boredom threshold, Conran was perhaps more editor, merchandiser and interpreter than a designer per se. His Midas touch shaped and led public taste, with looks and scenarios that enticed consumer-driven acquisitiveness, sometimes omitting to give due credit to others. As Bayley terms it, “he turned ‘design’ from being a description of something people do, to a commodity, something you can buy in his shops”.

Puritan and voluptuary, a self-described “socialist of the Burgundy variety” who put his own aspirational lifestyle of Havana cigars, oysters and swimming pools on display, he defined his lifelong interests as food, interiors, buildings, offering new choices and experiences and persuading the British to stop “clinging to the comfort blanket of the past”. But like those eminent Victorians the Prince Consort, Sir Henry Cole and William Morris, Conran believed in the potential for progress in art and design. His considerable achievements were recognised when he was appointed Provost of the Royal College of Art, 2003-11, knighted in 1983, and made a Companion of Honour in 2017.

- Terence Conran, born 4 October 1931, died 12 September 2020