In our post-truth era, Jenny Holzer’s truism, Words Tend to be Inadequate, has never felt more true. And now, on this side of the Atlantic, two artists are channelling this slogan by making works that address the current unreliability of words.

Last month, Fiona Banner made her feelings on the inadequacy of language abundantly clear when, along with a group of Greenpeace activists, she deposited a 1.5-tonne sculpture of a full stop on the doorstep of the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). The granite work, Klang Full Stop (2020), was both a weighty message to stop illegal industrial fishing in marine-protected areas, and a protest against what she calls “the puffed-up slippery rhetoric of the government”.

Banner has been making giant sculptural full stops for more than two decades, but now she is repurposing them as agents for direct action, declaring, “They are the most simple gesture I could make. When language is used in a duplicitous way and words stop meaning things, then democracy dies.”

On the same day she delivered her craggy calling card, two more of Banner’s giant stone full stops were being loaded onto a Greenpeace boat at Tower Bridge. From here they were shipped up to Dogger Bank in the North Sea and dropped into the water to form part of a protective boulder barrier installed by Greenpeace to obstruct the bottom trawling fishing boats that are destroying the delicate ocean bed.

As well as weapons for environmental activism, Banner also sees her sculptures as “big, physical, absurd language used to create obstacles and also to call for a pause or a stop”. She calls them “mausoleums for language”, asking: “Where do we go when the words we use cease to be charged in the way we want them to be? Or when agreements are not adhered to, and when we are completely exasperated by how language is used as an empty currency?”

Banner was meant to have a major survey show earlier this year, but this was scuppered by Covid-19. Now, with two sculptures residing on the ocean floor and another currently incarcerated in a Westminster Council storage facility, after being swiftly removed from Defra’s entrance, there is an added resonance to the billboard that she is displaying this month in the grounds of the Phytology cultural institute in East London, which starkly states: “The Retrospective has been Cancelled.”

Fiona Banner sees her sculptures as big, physical, absurd language used to create obstacles and to call for a pause or full stop

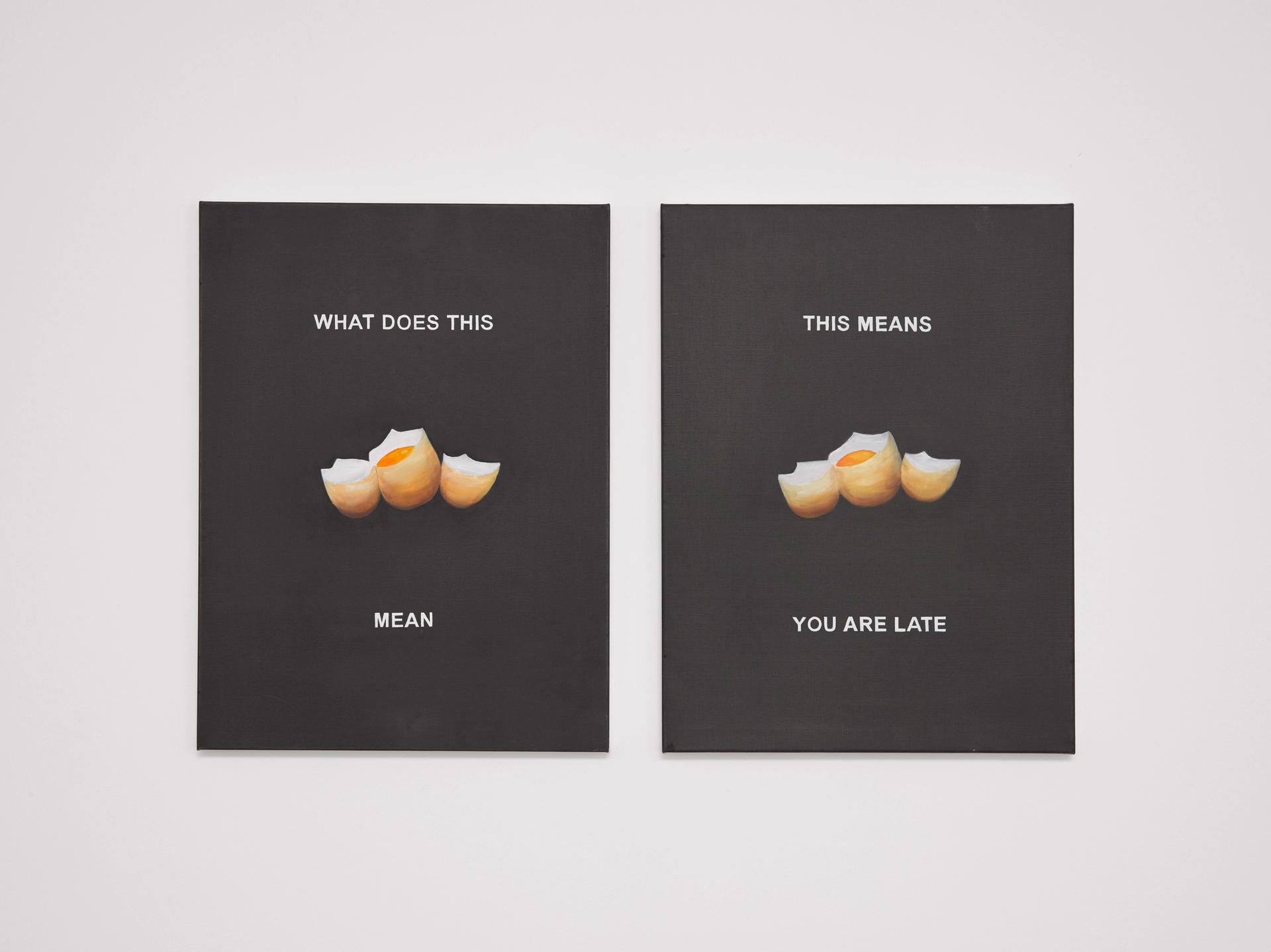

Laure Prouvost, THIS MEANS YOU ARE LATE (2019-2020) © Laure Prouvost, courtesy Lisson Gallery

Language is not killed off but reinvented in Laure Prouvost’s Re-dit-en-un-in learning CENTER, which occupies all the spaces in Lisson Gallery’s main building (until 7 November). Here, the French-born, Antwerp-based artist has created an all-encompassing fantastical education centre devoted to the “unlearning” of conventional words and “re-learning” of what Prouvost describes as a “new crypto-classification system”. This, she says is “a needed action in uncertain times”.

A series of diptych panel paintings pair images with words, while flashing lights and a staccato voiceover hammer their new meanings into the memory. We are instructed that a loaf of bread now means “work”, a glass is “mother”, a spanner stands in for “father” and “love” is expressed as a tangerine. while broken eggs mean “you are late”, with “you” now taking the form of a goat (apparently the result of Prouvost twinning humankind’s voraciousness with the goat’s omnivorous appetite).

Anyone who experienced Prouvost’s French Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale knows that she is an ardent maximalist whose work offers a multisensory, ritualistic experience in which the ordinary becomes ever more bizarre and vice-versa. In her Lisson Gallery language academy, new realities are formed while at the same time being wrong-footed by a plethora of emotive mixed messages.

Perhaps in tribute to our new identity as goats, aromatic hay is scattered underfoot and one gallery is filled by an entire felled tree that has been meticulously carved and manipulated to act as a hybrid host for unruly elements of Prouvost’s new lexicon. Walnuts cluster in its crevices, udders erupt from the trunk and droop from branches held up by metal props, while hand-blown glass tubes and vessels, a frying pan containing a glass fried egg and a goat’s head all protrude from its extremities. Many of these same images are then reinterpreted in a new video work which is viewed from inside a chamber cocooned at the centre of a fabric spiral.

Exiting through a trippy departure room bathed in yellow light, where ceramic udders point the way back to the real world, comes the realisation that, amid the absurdity of these exaggerated environments and her bizarre alternative language, Prouvost is making a serious point. Time spent in her “relearning centre” gives the opportunity to unpick conventions, question assumptions, and to read the world in a radically different way. This interrogation of the parameters of language by both Banner and Prouvost is exactly what is required when all around us tales are being spun. For, in the words of another Holzer truism, You are Responsible for Constituting the Meaning of Things.