A thousand fake OxyContin bottles floating in the waters of the Met’s Temple of Dendur, a blizzard of prescriptions raining down from the atrium of the Guggenheim, dozens lying “dead” in the porcelain courtyard of the V&A, blood-soaked Oxy dollars littering the steps of the courthouse. We woke the art world up to the reality that they were funded by addiction and death.

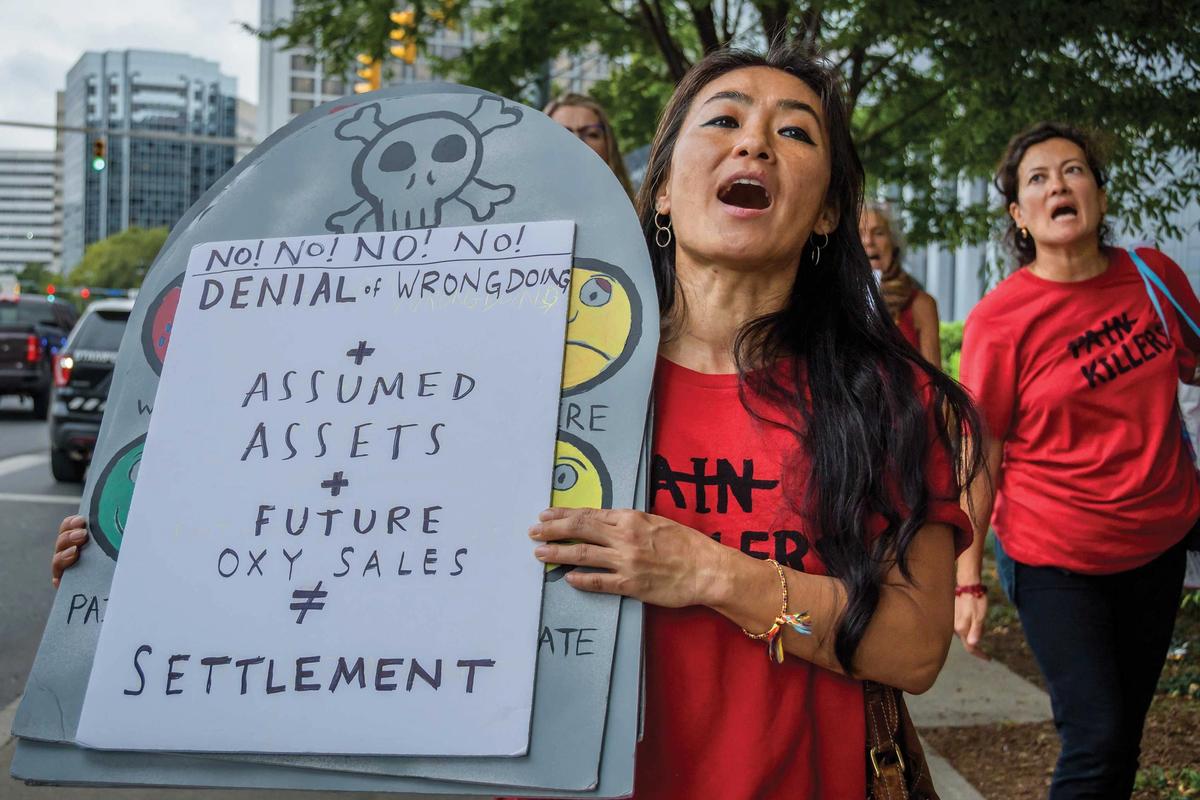

Pain (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) started as a direct action group in 2018. Our goal was to shame the Sackler name. We were also told to back-off, that philanthropy is complicated. We realised that the elite were immune to consequence. But then, a domino effect occurred and, one by one, museums stopped accepting their funding. “Sackler” became synonymous with the opioid crisis. The family* can no longer use philanthropy to wash their blood money.

Opioid overdoses have been ravaging Americans for two decades. Half a million people have been killed by this man-made plague, the origins of which can be traced to one family, the Sacklers, and their private company, Purdue Pharma. At the launch of OxyContin in 1996, Richard Sackler knew how lucrative it would be to overprescribe the highly addictive drug. He boasted its debut would “be followed by a blizzard of prescriptions that will bury the competition”. Richard was right—the Sacklers got their blizzard, and the country got buried.

As the Sacklers were ousted from museums, they went looking for protection from another institution that has long favoured the wealthy and powerful: the US court system. There, they are protected by a flotilla of the most expensive lawyers who have engineered a bankruptcy deal that will grant them immunity from future liability. It is clear that there are two justice systems: one for the billionaires and one for the rest of us.

In this environment, Pain is once again an unwelcome guest, exposing what we understand to be Purdue’s schemes and presenting facts that other players in the bankruptcy case often ignore: the bribing of a medical record company to push doctors to prescribe their opioids (as reported by Reuters); the injunction that shields Purdue’s owners from future lawsuits across the country; and proposed multi-million-dollar bonuses for its executives, even after the company declared bankruptcy. The court has ruled against us every time, so far. They underrate us because we are so few. But look at what Pain has done with only a dozen members. Now, we have formed the Ad-Hoc Committee for Accountability, with parents who lost their children to OxyContin, pushing for the public disclosure of all of Purdue’s records.

The Sacklers hope to strike a deal for immunity with the Department of Justice (DOJ) by Election Day (as reported by the New Yorker). We need to act fast. On 15 October, Members of Congress wrote to Attorney-General William Barr about their “deep concern regarding recent alarming reports suggesting that Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, and members of the Sackler family are nearing a plea agreement with the Department of Justice, which would foreclose any federal criminal liability without a single person serving a single day in prison”.

Congress must do more than write letters. It must hold hearings in which the Sacklers and victims of their opioid profiteering are called to testify. The family must not escape with their billions. Just as tobacco executives answered to the nation under oath about their misconduct, so should the Sacklers. Survivors and advocates deserve a chance to tell their stories. We will continue to fight our institutions to address the injustice of the opioid epidemic. While we fear the Sacklers will buy their way out as they always have, but they can’t buy back their reputation.

• Nan Goldin is an artist and activist. This was written in collaboration with Harry Cullen, Megan Kapler and Mike Quinn—members of the organisation she helped found, Pain (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now)

* Editor’s note: Arthur Sackler, one of three brothers who built up Purdue Pharma, died in 1987, before the development of OxyContin, and his heirs sold their interest in the company before its release