Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) was a dealer, writer, tastemaker, collector, likely a bomb-maker, and surely the most passionate promoter of Seurat, Signac, Matisse and Bonnard. He was also a trailblazing advocate of African and Oceanic art. For this delicious exhibition, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and the Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie and the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris collaborated, drawing from each museum’s expertise.

With a beautiful, intelligent catalogue, the exhibition links art, artists, theory, the market, writers and politics in a coherent package. Foremost, I love the show because it stars an art critic. There’s hope for we word-sluggers yet.

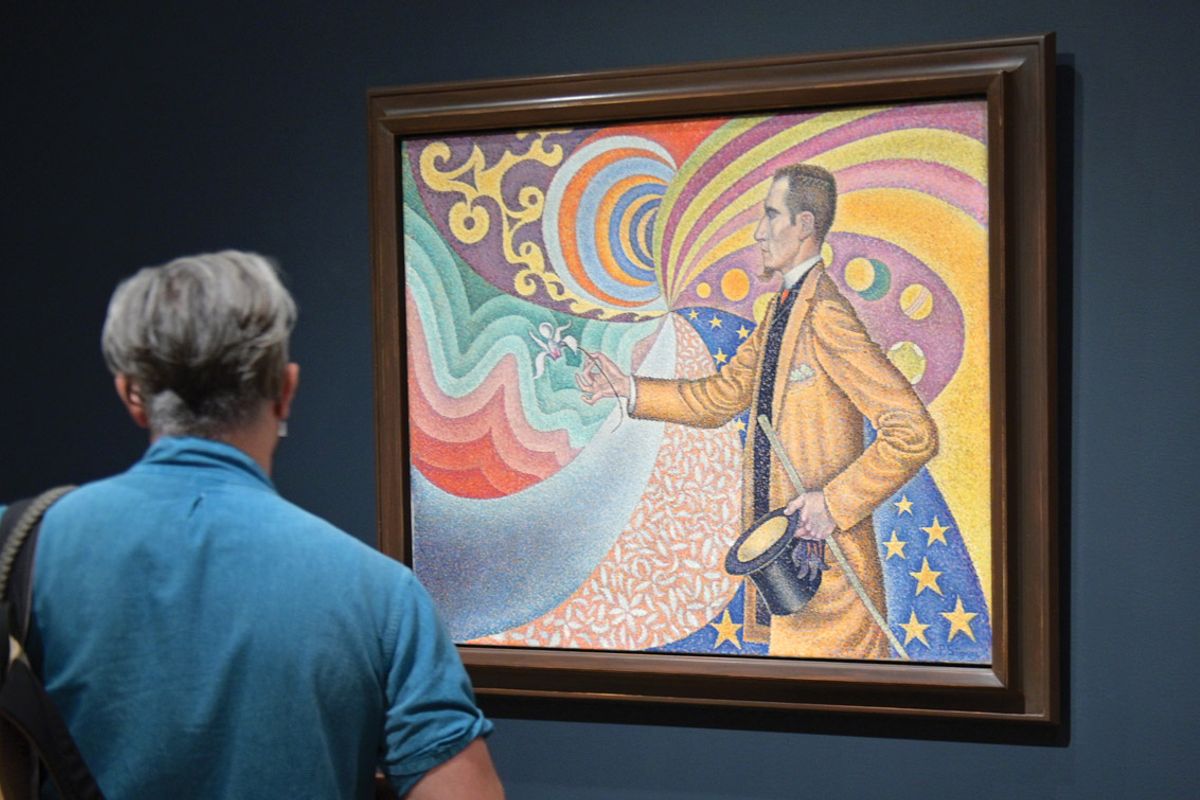

The show begins with Signac’s portrait of Fénéon, Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, from 1890. It’s a portrait but also a seminar, led by Fénéon and about Fénéon and the art he championed. The pinwheel of rainbow-colour dots unwinds the idiosyncratic colour theory Signac shared with Seurat and the other Neo-Impressionists.

What is Fénéon? He called himself “a hyphen” between the artist and the public when he defined what a dealer does. He strides with grace and confidence, top hat in one hand, a flower offered in another. His astringent thinking, charm and prowess as a writer make him a force of nature. Who is Fénéon? He’s sharp and determined, with a vision and a discerning eye. He’s a self-made dandy and physically riveting, yet smooth and subtle—what his god-daughter called “cautious and silent like a large cat”.

Neo-Impressionism, aside from the superstar Seurat, is considered a niche movement between the big beasts Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh, and, around 1907, Picasso and Matisse. The exhibition gives us so impressive a feast we come to think “niche” is not at all fair. There are plenty of Seurats, among them three small nudes from the Musée d’Orsay once in Fénéon’s collection and displayed side by side.

Fénéon adored above all else the art “of dream, of silence, of slow movement, of peaceful beauty”

They were his favourite things and I can see why. Like the many Seurat drawings on view, they’re as cryptic and personal as dreams. They’re sexy and cerebral, and depict what’s perfect about a woman’s body once it’s not carnal but soulful. Fénéon adored above all else the art “of dream, of silence, of slow movement, of peaceful beauty”.

Henri-Edmond Cross’s Les Iles d’Or from 1891 is a seascape of undulating rectangles starting as limpid sand and blue water that darkens in bands until it reaches islands and faraway clouds. Signac, Fénéon’s best friend, gets short shrift from art historians. Beauty doesn’t do the trick for them, but Setting Sun from 1891 is one knockout painting.

Fénéon lived a double life. By day, he wrote, cajoled, socialised and, of course, looked at lots of art. By night, he was an anarchist. The catalogue gives us a good look at anarchism in Paris in the 1890s, describing a movement that sought utopian joy through smashing authority. Fénéon’s aesthetics and politics, the catalogue argues, went hand in hand. In Neo-Impressionism, individual touches of paint enhance or subdue their neighbours to create luminous, harmonious results. There’s no hierarchy. The catalogue is strong in describing Fénéon’s politics, and I wish the show did more with it.

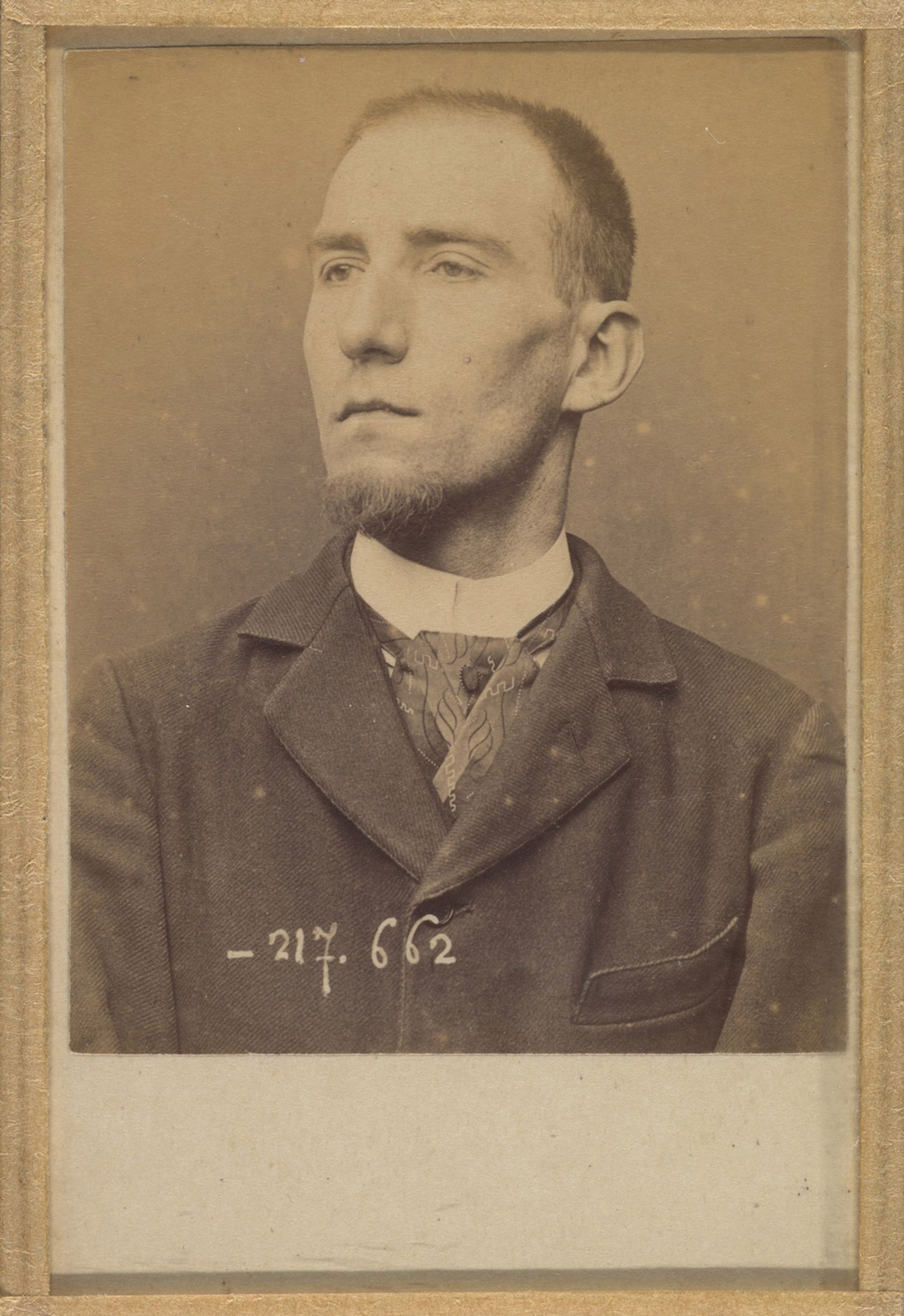

Félix Fénón photographed by Alphonse Bertillon in 1894 Photo: Alphonse Bertillon; courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

In 1894, Fénéon was one of the defendants in the then-sensational Trial of the Thirty, a criminal case aimed at breaking the back of anarchism in Paris. Charged with conspiracy, Fénéon got the better of the prosecutor, tossing quip and quip as freely as his fellow anarchists tossed bombs:

“Are you an anarchist, M. Fénéon?”

“I am a Burgundian born in Turin.”

“It is documented that you were intimate with the German terrorist Kampfmeyer. Is this true?”

“The intimacy cannot have been great as I do not speak German and he does not speak French.”

“It has been established that you surrounded yourself with Cohen and Ortoz.”

“One can hardly be surrounded by two persons... you need three.”

On and on, and the hapless prosecutor lay defeated, slain by the defendant’s stiletto wit. He was acquitted. Fénéon’s a funny guy, and his humour’s one of the pleasures of the show, but he was also what we’d call a domestic terrorist. He was certainly involved in bombings where innocent people died.

The curators probably think plumbing anarchist politics is too heavy for the public. Neo-Impressionism, though, was so political a movement, and Fénéon so committed to it, that the show needs the explication of the trial and milieu the catalogue gives. Visitors can make their own judgments.

Fénéon was hired in 1906 as a contemporary art dealer at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, which dealt heavily in the Impressionists but wanted to include new artists. Fénéon had intellectual chops rare in the trade; he was smooth with buyers, fulfilling their quest to buy art for decoration but also making them feel they were on a daring, edgy adventure. Bohemian, anarchist artists and rich buyers trusted him.

Here, Matisse, Bonnard and the Italian Futurists come into his life. The 1912 exhibition of Italian Futurist art at Bernheim-Jeune was Fénéon’s doing. It launched Marinetti, Boccioni, Balla, Severini and others in the Paris market. The Italian things end the show with a blast. Balla’s Street Light from 1910-11 and Carra’s Funeral of the Anarchist Galli from 1910-11 are big and smashing. The sale was one of many hits in Fénéon’s 20 years there.

Above all, Fénéon was no snob. “Day’ll come, Goddam, when art will fit in the life of ordinary Joes like steak and vino,” he wrote. He abhorred barriers like class, academic gobbledygook or subject matter remote from everyday life. The art he loved and advanced is polemical only in the sense that beauty feeds every soul.

Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading, 1905-06) by Henri Matisse, of whom Fénéon was a passionate promoter Photo:y Paige Knight; © 2019 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society

In recent times, Ileana Sonnabend and Edith Halpert, towering dealers, have found their place in the sun through museum shows, as have, less definitively, Theo Van Gogh, Alfred Stieglitz and Ambroise Vollard. The MoMA show encourages scholars to look at the outsized influence of other dealers. They’re in the trade, yes, but the best are as passionate about art as any critic or scholar. Without a persuasive, perceptive dealer, many of our greatest artists would not have had careers.

Fénéon was one of the earliest collectors of art from Africa and Oceania. At his 1944 estate auction, 437 objects from this part of his collection sold. His interest started in the 1890s, the catalogue tells us, from his anarchism and anti-colonialism. Fénéon looked, gullibly or not, for new Edens, and what better Eden than ones untouched by urbanity?

His collection in this area was of a piece with all the art he loved, all “steak and vino”. Systems like Neo-Impressionism are made of small parts that, individually or as a whole, anyone can appreciate. Using simple, un-gussied forms, Fénéon felt, African art appealed to the spiritual inside everyone.

Until Helena Rubinstein started collecting African art, no one of Fénéon’s discernment focused on it. The excellent, essential catalogue considers the critical reception of Indigenous art, especially Fénéon’s advocacy of its value in French national collections.

Aside from enhanced treatment of Fénéon’s Anarchism, I think the exhibition needed an expansive look at his collecting, especially its fraught disposition, and his relationship with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jules Chéret, who get a small wall. Still, it’s a sign of a stellar exhibition and catalogue when the critics cry: “more, please”.

• Félix Fénéon: the Anarchist and the Avant-Garde—from Signac to Matisse and Beyond, Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 2 January 2021