As the 2020 election approaches and concerns of voter intimidation and suppression continue to arise, an exhibition at the Cooper Union in New York considers the history of election ballots. The evolution of their design is an overlooked concept that has “shaped the American democracy but has been filled with fraud and fraught with corruption since its inception,” says the curator, Alicia Cheng.

This is What Democracy Looked Like: A Visual History of the Printed Ballot (until 7 November) will be visible from the streets on the Fourth Avenue side of the Cooper Union building and showcase 26 colourful, ornate election ballots chronicling more than seven decades of the US voting system, which aim to demonstrate the development of this still-imperfect procedure.

With a background in graphic design, Cheng was inspired after reading a 2008 New Yorker article by Jill Lepore on early voting practices, and the propaganda-like nature of their design before the 20th century. It prompted her to write one of the first books on the subject, which was published this past summer.

“The ballots were colourful and ornate, so that piqued my initial interest, but in 2016, when things got horrible, I doubled down and began to wonder whether our republic had survived trauma like this before,” she says. “These artefacts became a broader nexus for concurrent stories that were happening in the 19th century like suffrage, the electorate, the population explosion, immigration and so on.”

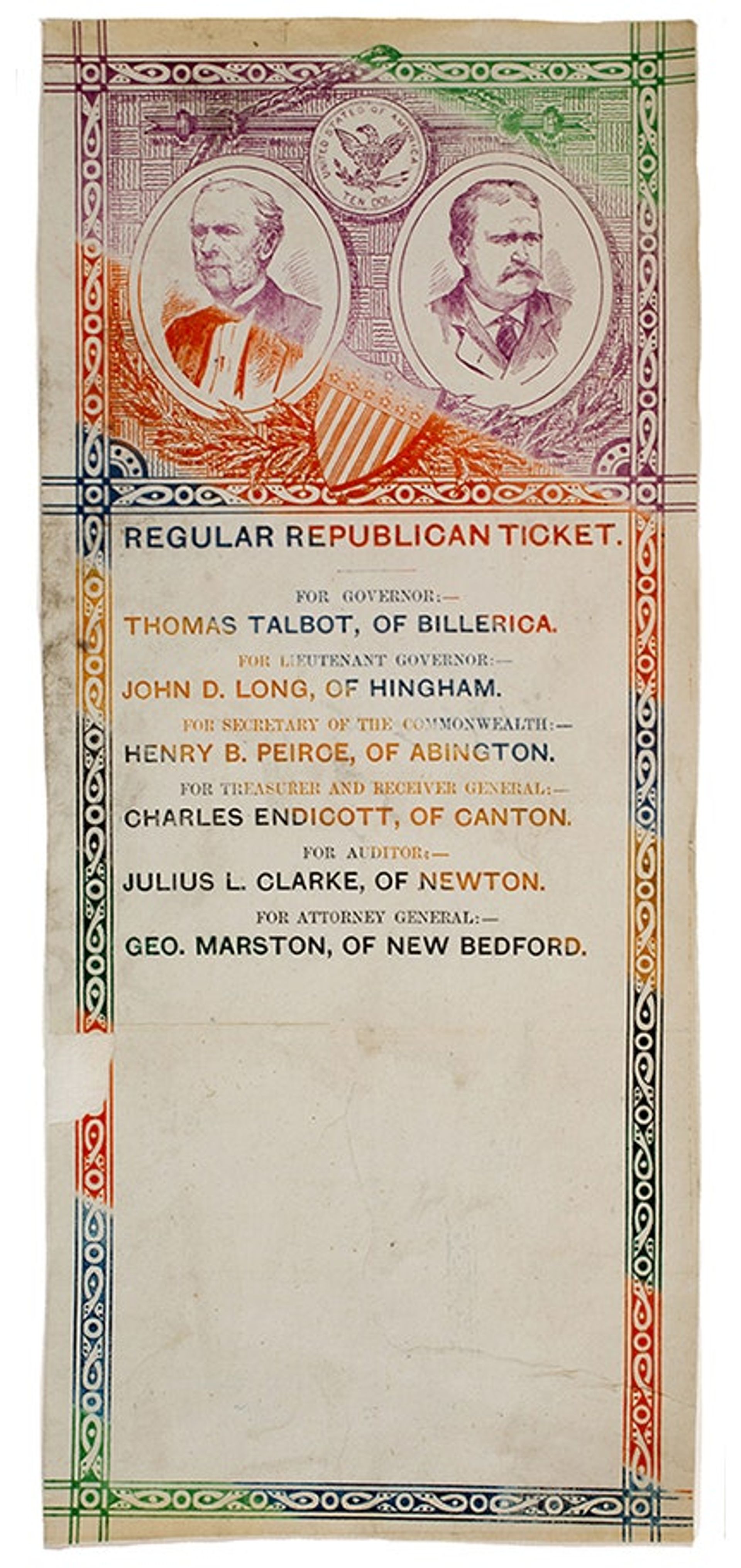

This Republican ballot from 1878 shows the “split fountain” printing technique, which involved the application of multiple coloured inks onto a roller. Courtesy of the Cooper Union

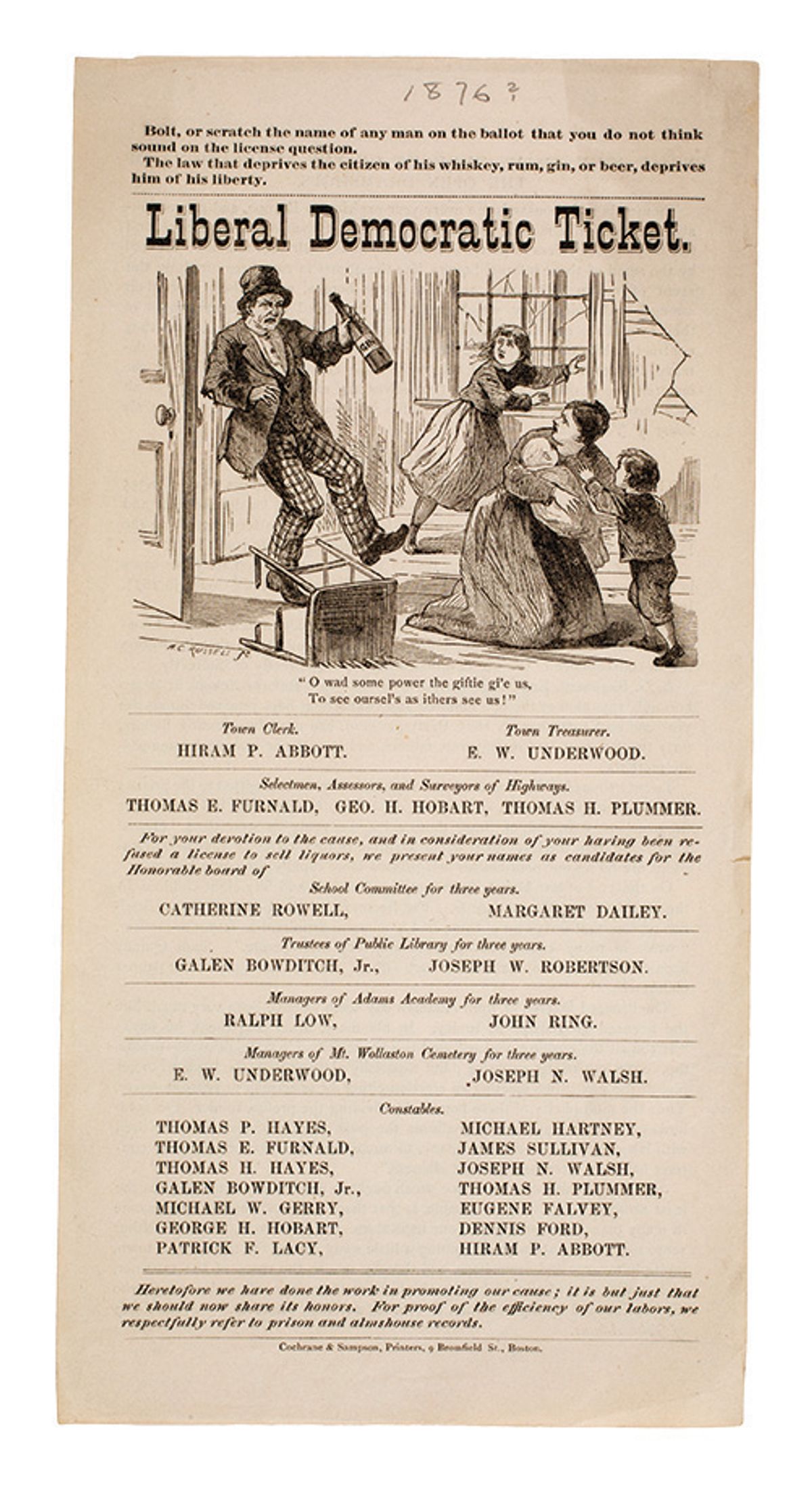

Before the 20th century there was no federal oversight for the election ballot. In fact, until the mid-1890s, election ballots were produced, printed and distributed by the parties themselves, and operated as a single-party ticket, with votes cast into a public and easily hackable box. The colourful two-sided ballots made voters “walking billboards” for political offices and allowed poll watchers to evaluate whether voters “were making the ‘right’ decisions”, Cheng says.

“There are also hilarious and outlandish stories of people voting multiple times in a day by beginning the day with a full beard and ending the day clean shaven to impersonate different people,” she adds.

While some ballots highlight moral issues like temperance, other ballots contain racist or xenophobic elements that served to illustrate what the political parties might espouse. Among the more lurid examples is a San Francisco ballot that explicitly runs on an anti-Chinese platform, while some are more subtle in their messaging.

Elaborately designed, eye-catching ballots aimed to not only vocalise voters’ political leanings but also simplified the process for illiterate persons. “It was easier sometimes for people to vote for the chicken or the ship versus having to read through candidates, like the dense and typographic material that we have now,” Cheng says.

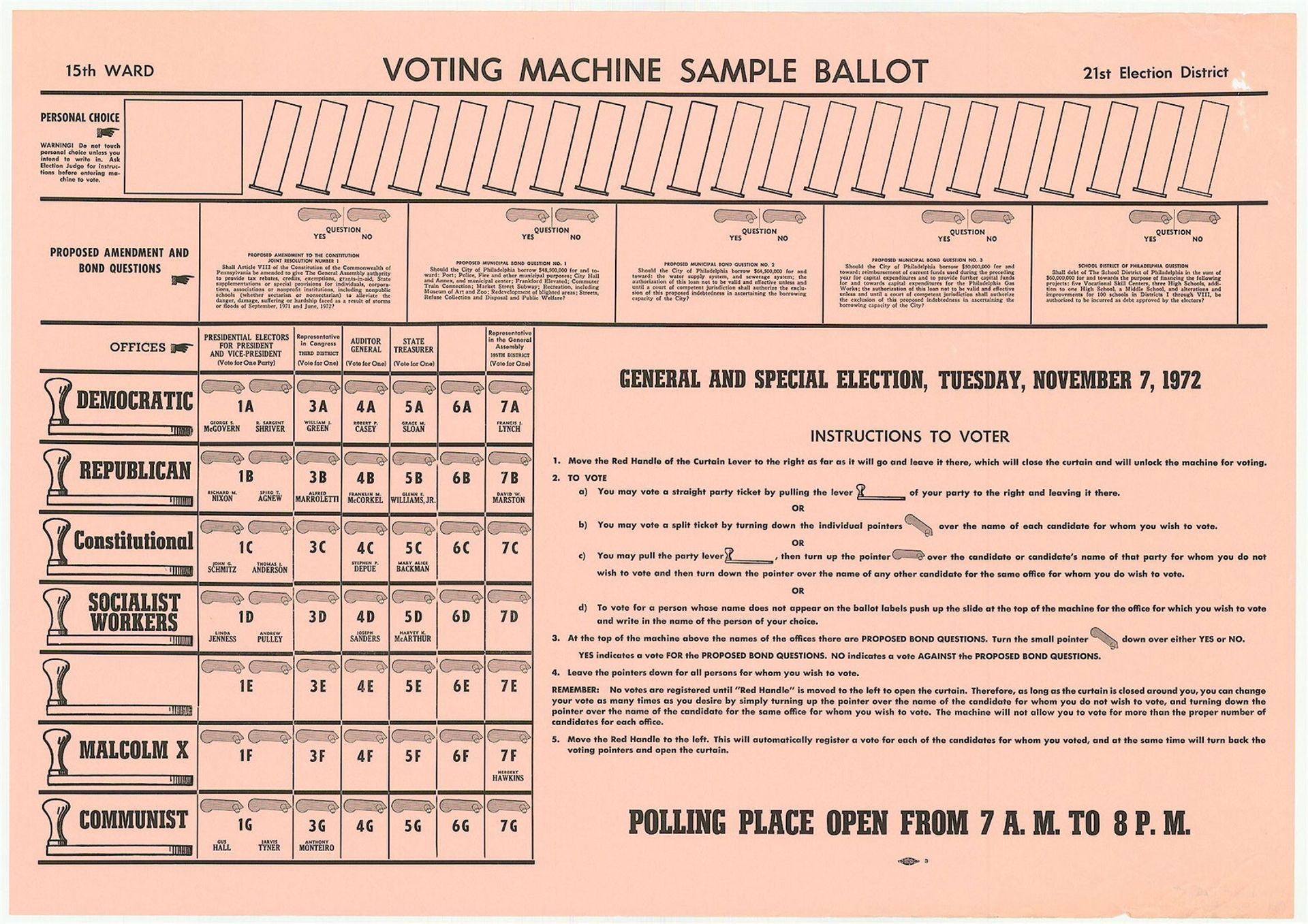

Ballots grew more typographically dense in the 20th century, like this one from 1960. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Federally-regulated ballots similar to what present voters are accustomed to were introduced in the early 20th century. But the modern format continues to cause confusion and complications, like the now-infamous 2000 “hanging chad” conundrum in Florida where some paper ballot holes were not punched through completely, as well as the current battles around mail-in voting fraud and disenfranchisement, heightened by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Cheng sourced the ballots from places like the Huntington Library in Los Angeles and the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, but notes that a comprehensive repository for these ballots does not exist since ballots are intended to be destroyed for the sake of security after elections. “As I heard one collector say: these ballots are the most fugitive form of ephemera,” she says.

They are also “an incredible reminder of the power of design in our civic process, and are both a visual delight but also an important educational tool for learning about how our democracy has evolved and how it has stagnated,” Cheng says. “The resonances are both fascinating and super depressing.”