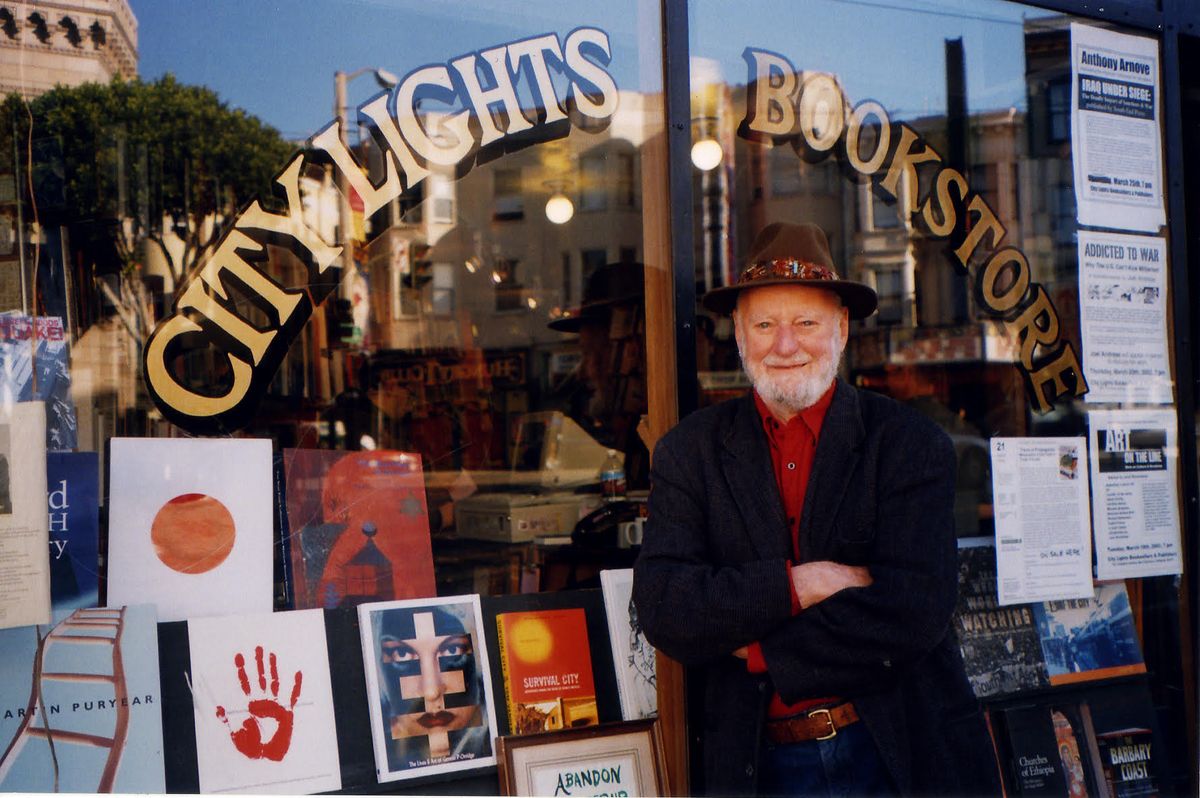

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the 101-year old poet, painter, and activist, is perhaps best known for his founding of San Francisco’s City Lights Bookstore, which he opened in 1953 in the city’s North Beach neighbourhood, and which still stands there today. Though Ferlinghetti does not identify as a Beat poet himself, he played a hugely influential role in that literary scene, and in 1955, City Lights were the first to publish Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, which led to Ferlinghetti’s arrest on charges of printing and selling lewd and indecent material. He fought the charges and won the case two years later, setting a landmark precedent for free speech in the US.

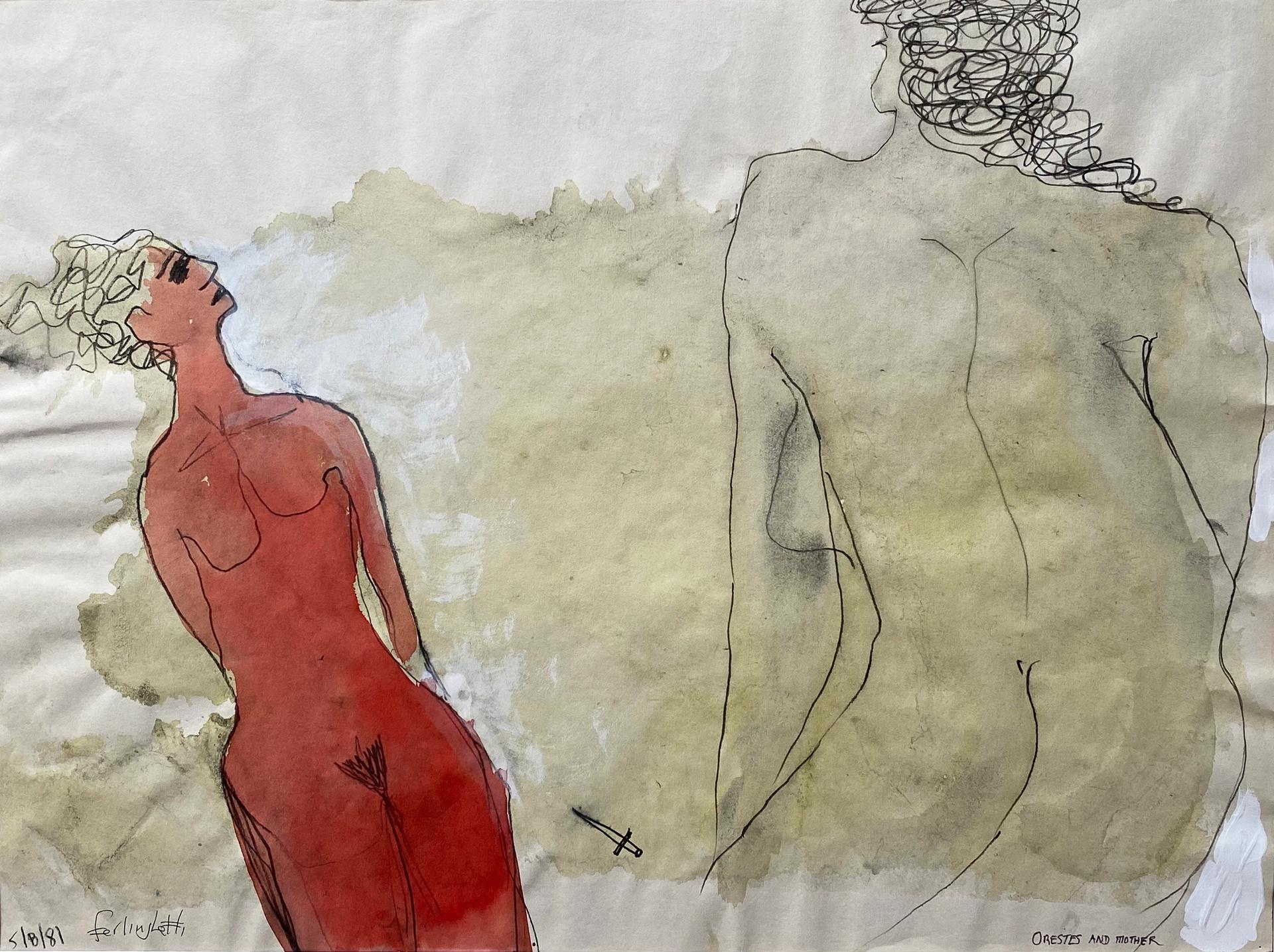

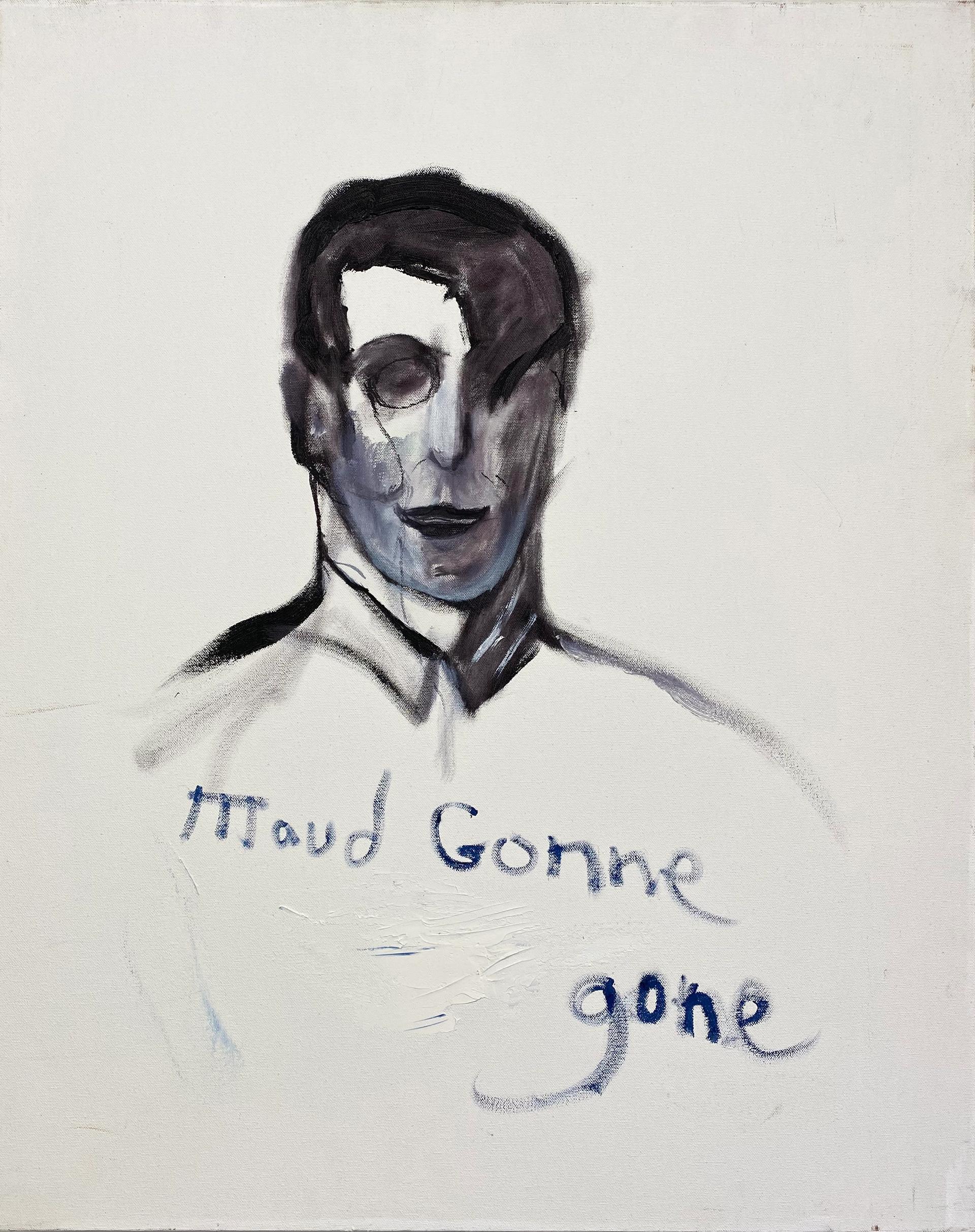

Ferlinghetti has also been painting for more than 60 years, and has shown his works throughout the world. A suite of his paintings and drawings from the 1980s through to the present day are on view in Études, a solo exhibition at New York’s New Release gallery, through 16 October. Many of the works combine image and text, while some paintings like The Young Yeats (2008) reference Ferlinghetti’s deep connection to poetry. Others, such as Icarus Blind (1989) and Orestes and Mother (1981) show his long fascination with mythology. The Art Newspaper spoke with Ferlinghetti over the phone and by email from his home in San Francisco.

The Art Newspaper: You’re most famous for your contributions to American poetry, but were you ever trained as an artist?

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: No, I was totally on my own, I had a model regularly in my studio at Hunter's Point but there was no instruction.

I used to go to the open studio in Paris at the Atelier Libre but I never had any kind of discipline.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Orestes and Mother (1981) Photo: courtesy of New Release gallery

Who are your artistic heroes? Who do you look to for inspiration?

Artistic heroes, well… Goya is the first that springs to mind, he was very important. I learned a lot from Goya.

Do you remember when you first saw Goya's work?

Probably when I was a graduate student at Columbia University. I did an MA thesis on Ruskin and Turner.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, The Young Yeats (2008) Photo: courtesy of New Release gallery

Can you tell us about your painting Young Yeats on show in New York? You wrote on it "Maud Gonne Gone"?

Maud Gonne was his long-time hang-up, his girlfriend that he pined after—but she rejected him, she married a sergeant or something in the Irish military. But Yeats never gave up—he still longed for Maud Gonne.

What’s the relationship between the image and the text in your paintings?

Well, most painters don't use much in the way of literary quotations and I wish they would use more, be more specific, but generally it's not their "thing" to get into the literary part of painting.

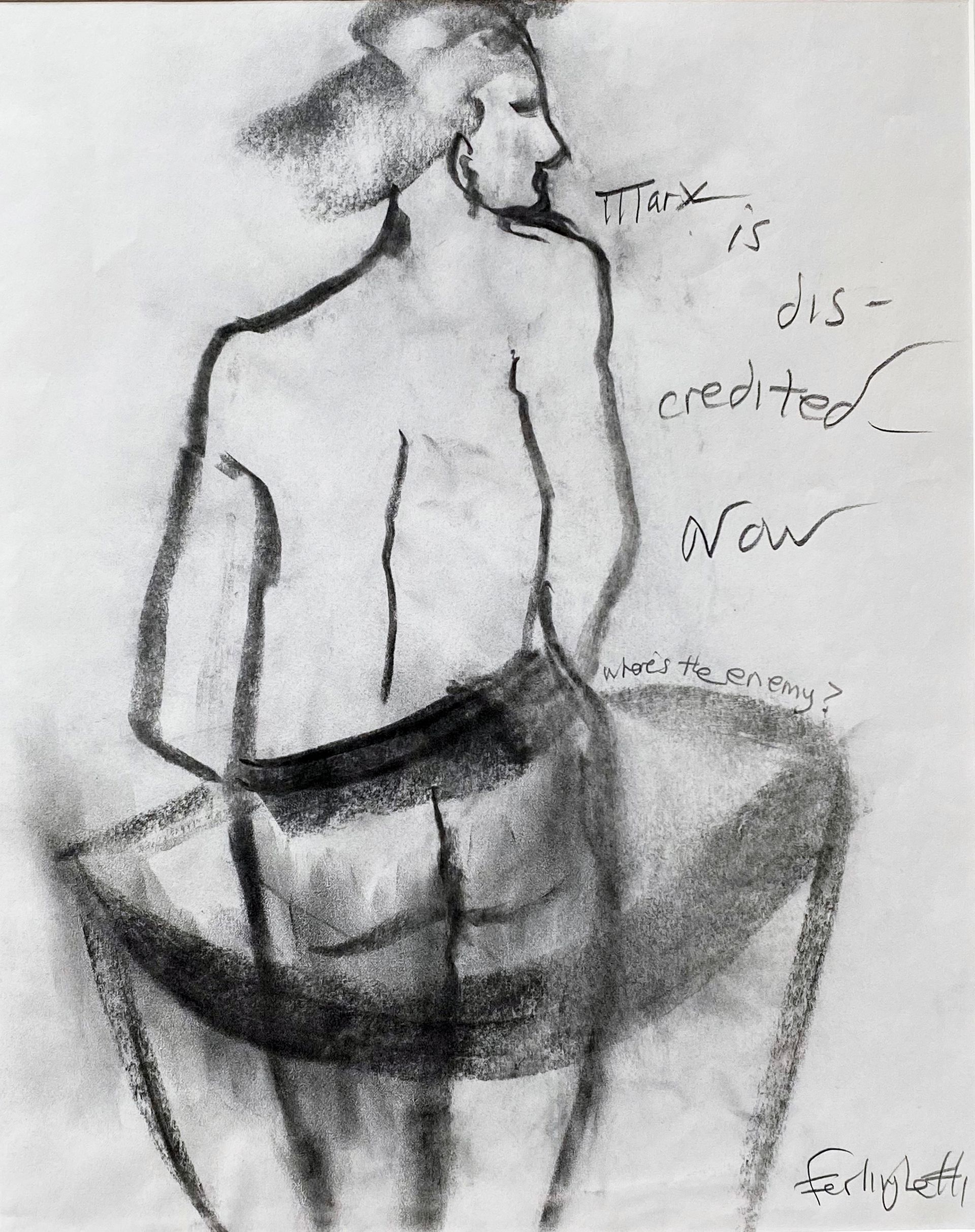

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Marx is discredited now… (1999) Photo: courtesy of New Release gallery

What about your sketchbooks and drawings—you do figure drawings with a model, but do you go back and add the quotes later?

No, I usually do it at the same time as I did the sketch—if there's any words on the page next to the sketch, I didn't add them later.

You have always insisted that your literary work and your artwork were completely separate...

Yes, they were…

...but they seem connected because of the way that you use literary references in your artwork, and the way that you use artistic knowledge in your writing.

Yeah, you're right—you're perfectly right on that.