Here we go again. As I illustrate in my recent book on the history of deaccessions, the UK Museums Association cautiously opened the door in 2008 to a more relaxed posture towards deaccessioning through a circular entitled “Too Much Stuff?” The hope was that regional museums would react to the more permissive atmosphere by disposing of low-value, redundant works that were clogging up storage rooms and would unlikely ever be on display. On the contrary, several institutions took the occasion to jettison instead the most valuable masterpieces in their midst, to raise substantial funds for building repairs and other capital improvements wholly unrelated to collections care.

Unfortunately, the recent modest relaxation of the use of deaccessioning funds by the US Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), which now allows for the proceeds to be deployed for the “direct care” of collections for the next two years, has occasioned a similar onslaught of unbridled commodification by a few museums. The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), in particular, is uniquely egregious in this regard, and its sycophantic rationalisations to the press do not pass muster on further inspection and should not stand unchallenged.

Emboldened by the muted reaction to its recent sale of works by white male artists to raise funds for acquisitions of under-represented artists, the BMA is now proposing the sale of three major works to redirect funds to overcome “inequality” in staffing and salary levels. Christopher Bedford, the director, has mobilised these well-intentioned critiques of inequality at museums to justify a wholly unrelated looting of some of their most valuable works without a compelling and defensible curatorial rationale.

For example, defending the disposal of an oil on canvas by a leading living artist, Brice Marden, Mr. Bedford had the temerity to profess to The New York Times, “Marden’s contribution to the history of art is more richly narrated in our works on paper holdings than a single painting.” He likewise told The Art Newspaper, “We are very sensitive to Brice Marden’s place in history. But it’s established with great force and clarity through our holdings of works on paper,” which he describes as “compelling and subtle”.

Anyone can search the museum’s online collection for works by Marden, and even a cursory review of its holdings illustrates that nothing could be further from the truth. Of the 16 so-called “works on paper” Bedford heralds, 15 are in fact small etchings or screenprints, mostly from the Focus (1979) and Zen Study series (1991); the BMA has only one unique “work on paper” by this artist, an untitled small pen and brush work from 1974).

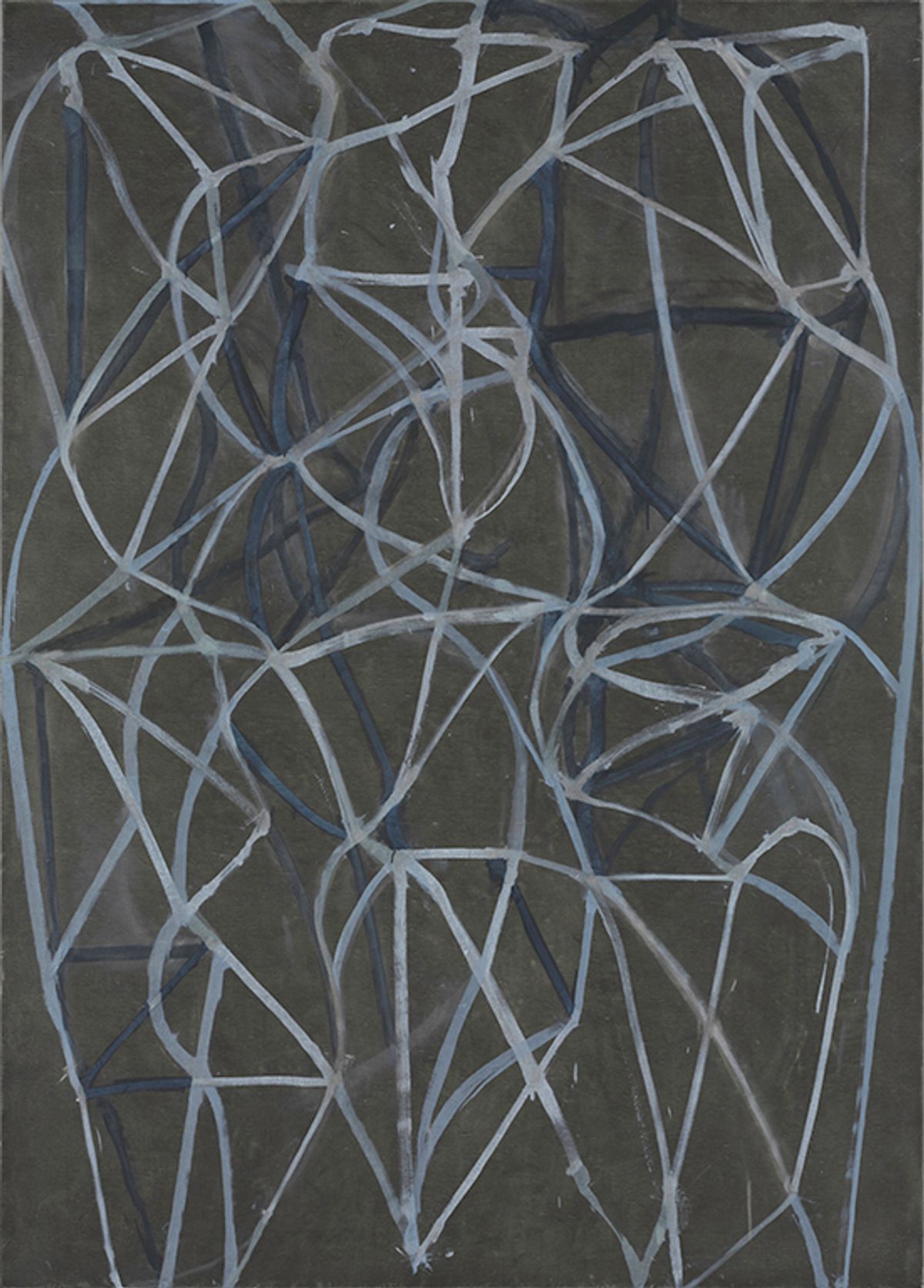

The 15 Minimalist etchings it does retain cannot possibly stand in for the powerful art historical resonance of his one major oil on canvas in the collection that is proposed for sale, 3 (1988), one of Marden’s acknowledged masterpieces from the late 1980s. Indeed, the BMA was fortunate to acquire it right after it was exhibited at Mary Boone Gallery in 1988, with funds from the Harry A. Bernstein Memorial Collection, presumably because the artist’s dealer was eager to see such an important work in a museum collection.

Marden himself has singled out this painting as one of the first in which he engaged with the figure of the “Hour” in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, an engagement that became a central concern in the series of works he later produced that meditate deeply on Botticelli’s oeuvre.

A detail of Botticelli's The Birth of Venus (around 1482-85)

One can see the lineaments of his unique mode of abstraction emerging from his deep engagement with the compositional depth of Botticelli’s precedent in this seminal painting. It is therefore simply grotesque for the BMA to profess that losing this pioneering work arising from his deep interlocution with a landmark work in art history will somehow be recompensed by the small clutch of Minimalist etchings left in storage. That frankly does not come close to passing the smell test.

As such, while there is simply no defensible curatorial rationale for this deaccession, the only remaining one is, sadly, pecuniary: it is one of the few purchased works at the BMA that is likely worth in excess of $10m, and therefore one of the few that could possibly satisfy its pre-ordained gargantuan ambition for a $65m “Endowment of the Future.”

Bedford likewise told The Art Newspaper that the Andy Warhol masterpiece now on the block, The Last Supper, “is close to meeting the definition of collection redundancy”. Supporting this contention at face value, The New York Times notes, “Warhol’s The Last Supper (1986), being offered by Sotheby’s through private sale, is a significant work from a major series but it is one of 15 paintings by the artist in the collection, many also late-career works.” Again, this apparent rationale that the painting is somehow redundant, as the BMA has many other late works by Warhol, rings completely hollow on closer inspection.

Andy Warhol's The Last Supper (1986), synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink on canvas Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art

Among those 15 works are at least eight that were acquired in part by museum purchase and are clearly more reasonable candidates for deaccessioning than The Last Supper—they are just not worth nearly as much.

For example, the museum owns no fewer than four polymer paint and silkscreens on canvas by Warhol from the Skull series, as well as two from the Diamond Dust and two from the Ladies and Gentlemen series—all of which were purchased in part with museum funds and therefore are not governed by the restrictions typical for disposing of works from donors. Given this duplication, the museum could have retained at least one of each group and then sold the duplicates, without greatly affecting the curatorial depth and diversity of its collection. Indeed, the selling of duplicates has been a central rationale that has successfully guided museum deaccessions since the 18th century, especially for works acquired by museum purchase.

However, works from the Skull, Diamond Dust and Ladies and Gentlemen series have typically sold at auction in recent years for about $1m to $1.5m, and it is clear from the BMA’s announcement that the museum is expecting something in the range of $40m in a private sale for The Last Supper, given its target of $65m in proceeds from the sale of the three works for a new endowment. As such, the sale of these obvious duplicates, while perfectly reasonable from a curatorial point of view, simply would not meet its predetermined financial targets.

Again, there is no defensible curatorial rationale that would foreground this painting over the evident redundancy of other late works by Warhol in the collection—the only conceivable rationale is the enormous windfall they would hope to reap by selling this singularly important work of art. Not surprisingly, Brenda Richardson, the former BMA curator who managed to acquire the Warhol for the museum in 1989 shortly after it was painted, told The Washington Post that she was “nothing short of horrified” by the plan.

Finally, the deaccessioning of the only painting in the collection by Clyfford Still, who spent the last 20 years of his life painting in the Maryland countryside near the BMA, is particularly outrageous. Still was notorious for eschewing the sale of his work in his later years, but he did donate major works to favoured institutions, and specifically chose this example to gift to his local museum. The work, 1957-G, was especially prized by the artist himself, and prominently featured in the last major retrospective he consented to at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo in 1959, which he curated.

Clyfford Still, 1957-G (1957), oil on canvas Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art

Given this history, it is inconceivable that Still would have ever warranted this proposed disposal—were he even alive now to defend himself— especially on the grounds of Bedford’s stupefying formulation of a “different definition of redundancy”, in which the story of Abstract Expressionism can somehow be deepened by future acquisitions of under-represented artists out of the proceeds from this fire sale. How can the story of Abstract Expressionism be “deepened” at the BMA by disposing of the only major work of one of its founding members, in direct conflict with the donor’s wishes?

In short, it appears more likely that the BMA, taking the AAMD’s cautious relaxation of the rules as a pretext, decided in advance that it would like to reap a $65m windfall to launch an endowment for operational purposes that can be nominally tagged as “direct care,”, and then redistribute funds from other sources that are freed up by this gambit towards shoring up some salary disparities and other inequalities having nothing to do with the direct care of collections.

Museums are facing desperate times, and many face challenges that make the temptation of deaccessioning seem like a panacea for their acute financial shortfalls. In some cases, it may be necessary to pursue strategic deaccessions in order to reduce excesses in storage and raise modest funds for the “direct care” of collections as the AAMD has proposed. However, selling major works of art under the cover of calls to restitute “inequality” is certainly not one of them, and it is quite dispiriting that the museum profession has not loudly condemned this reckless proposal at face value, as a fateful step towards the wholesale commodification of museum collections to satisfy any perceived financial impairment.

Martin Gammon is the founder and president of the art advisory firm Pergamon Art Group and the author of Deaccessioning and its Discontents: A Critical History (MIT Press, 2018).