For London’s National Gallery, the opening of its long-awaited Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition in the face of Covid-19 represents a tribute to the artist’s own indomitable spirit. Speaking in an online press conference today, the galley’s director, Gabriele Finaldi, said he hopes her example of conquering challenges will serve as an inspiration in tough times.

Artemisia, which opens on 3 October and runs until 24 January 2021, is the gallery’s first major show dedicated to a female artist in its 196-year history. It was originally planned for April and had to be postponed when the pandemic struck. Rescheduling involved delicate negotiations with lenders but Artemisia’s life story is “about overcoming difficult situations through sheer willpower and talent… and I think there’s some element of that in the way we worked on the exhibition”, Finaldi said. “I hope people will come and see the exhibition and use it as an opportunity to sense that we can get through the Covid crisis.”

Gentileschi (1593-1654 or later) was born in Rome, the daughter of Orazio Gentileschi, court artist of Charles I. Orazio trained her, but as a young woman she was raped by a fellow painter and then had to endure a horrific trial in which she was tortured to prove she was telling the truth. After her assailant was convicted, she moved to Florence and embarked on an unhappy marriage.

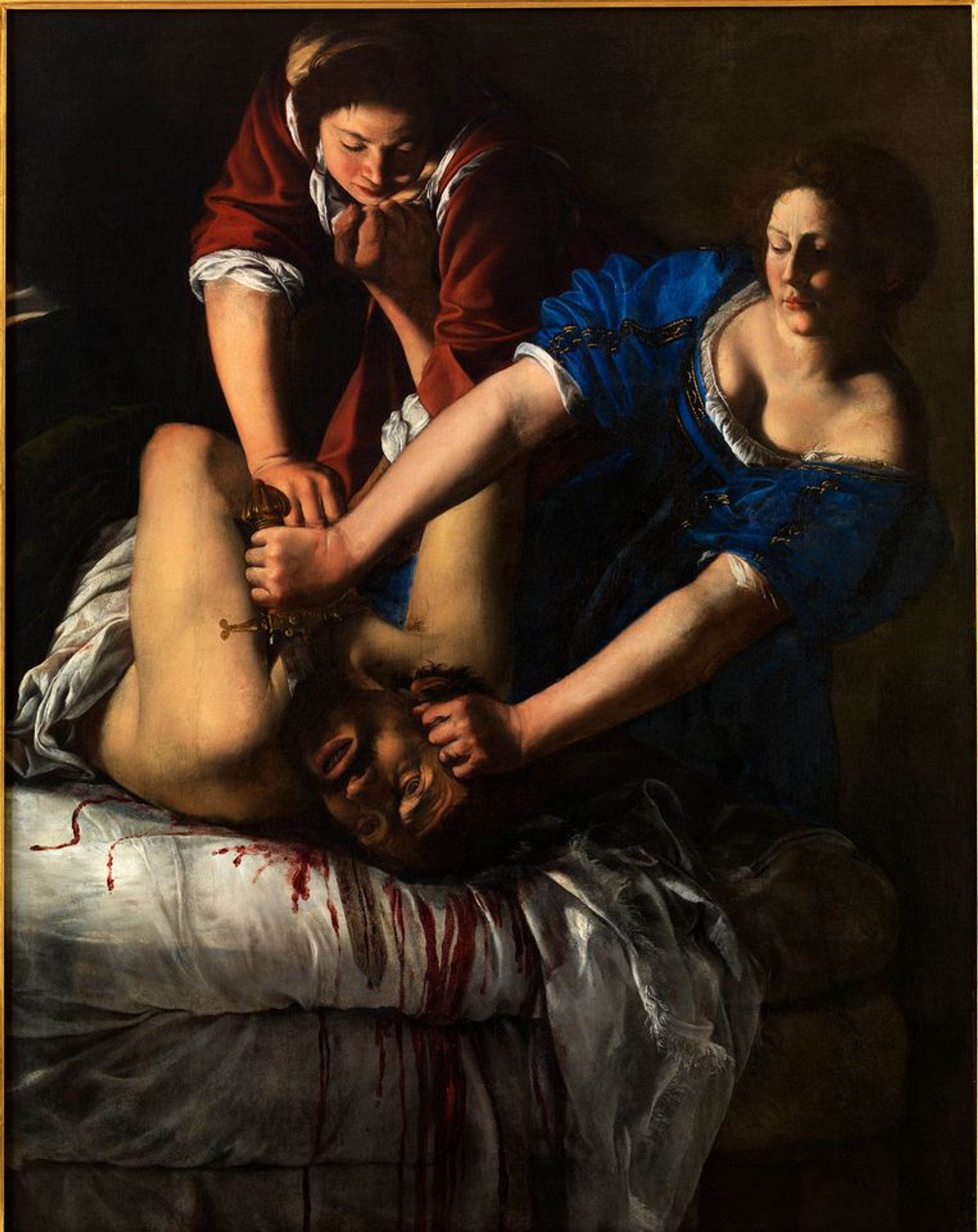

Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Holofernes (around 1612-13), one of two versions in the National Gallery exhibition photo: Luciano Romano; © Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte

However, Artemisia managed to establish herself as the most successful female artist of her time, says the exhibition’s curator, Letizia Treves, as well as becoming the breadwinner in her family and finding happiness with a lover, Francesco Maria Maringhi. A collection of letters between them was discovered in Florence in 2011 and will be on display at the National Gallery, the first time they are travelling outside Italy. “It’s a very intimate correspondence,” Treves said. “In one letter, she asks Maringhi not to masturbate in front of her painting.”

Highlights of the show include Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (1620-25), which only came to light in 2014, and two versions of Judith beheading Holofernes (1612-13 and 1613-14). These and other works reveal a distinctly female take on subjects often painted by male artists. “She imagines what it’s really like—she gets under the skin of the protagonist,” Treves said. Artemisia’s paintings provide “very truthful and unflinching” images, for example, of two women working together to kill a powerful man.

Finaldi said Gentileschi, who was rediscovered in the 20th century after being largely forgotten for centuries, was “very much in tune with our times”, while Treves thinks there are almost certainly more paintings by her still to be discovered.