Stephen Friedman’s gallery was not yet a year old when, in 1996, he got a stand in the hallowed halls of Art Basel. The young dealer clearly had chutzpah: he asked for—and got—a 30% stand discount and his own two-page insert in the fair catalogue.

Approached at short notice when another exhibitor pulled out, Friedman told the organisers: “I’d love to participate, I’m very flattered, but I have two requests—you’re giving me just a month to put together the booth so I’d like a 30% discount and I’d like you to consider putting a separate two page insert into the catalogue for my gallery.” From a friend of his parents’, Friedman procured a Gerhard Richter painting as the focal point of his stand. It sold on the first day for $250,000. "That painting today is worth $10m or $12m,” he says.

Born in Montreal, Canada, Friedman moved to London at 22 to study at Sotheby’s and fell for the city: “I love the humour, I love the people. It captivated me.” He has never left the UK and thinks himself fortunate as a Canadian: “I’m embraced by the community, but I’m also somehow forgiven for expressing my opinion rather vociferously.”

Friedman’s mother was an antiques dealer and he began collecting at the age of 13, when he used money given to him at his Bar Mitzvah to buy three traditional Canadian landscapes by Group of Seven artists. He still has one today, waiting to be hung in the house he is building in rural Dorset.

Mamma Andersson's The Horse, The Ghost, The Sun (2020) Copyright Mamma Andersson. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photo by Per-Erik Adamsson.

On graduating from the Sotheby’s course in 1990, Friedman immersed himself in the London art scene, befriending artists such as Peter Doig. He was a “jack of all trades—a writer, a private dealer, a sort of confidante to a number of young artists” and did a stint at Christie’s, as a contemporary art expert in charge of Scandinavia. He would return to Montreal frequently with a portfolio of drawings and photographs, setting them out on the floor and sofas at his parents’ cocktail parties and selling them to their friends. “I was a bit of a travelling salesman,” he says.

In 1994, he wrote a business plan for a gallery, anticipating that he wouldn’t make money for five years. In 1995, he opened a gallery in Old Burlington Street, Mayfair, and after two years it was turning a profit. Twenty five years later, Friedman still occupies that gallery—plus another on the street—and it is here that he has just opened his 25 Years exhibition (until 7 November), featuring works by all of the gallery’s 29 artists including Mamma Andersson, Kehinde Wiley, Lisa Brice, Denzil Forrester, Holly Hendry and Luiz Zerbini. During "Frieze Week" in October, the gallery will also occupy a third space on Old Burlington Street to accommodate the show, plus solo projects by Holly Hendry and Denzil Forrester (until 31 October).

Unusually, perhaps, Friedman has never expanded beyond this corner of London: “I feel like I haven’t even scratched the surface with the space I have in London,” he says. Now, with the coronavirus pandemic, he is increasingly focused on keeping the business “lean and efficient”. He is, he says, “a bit of a risk taker. But I take calculated risks.”

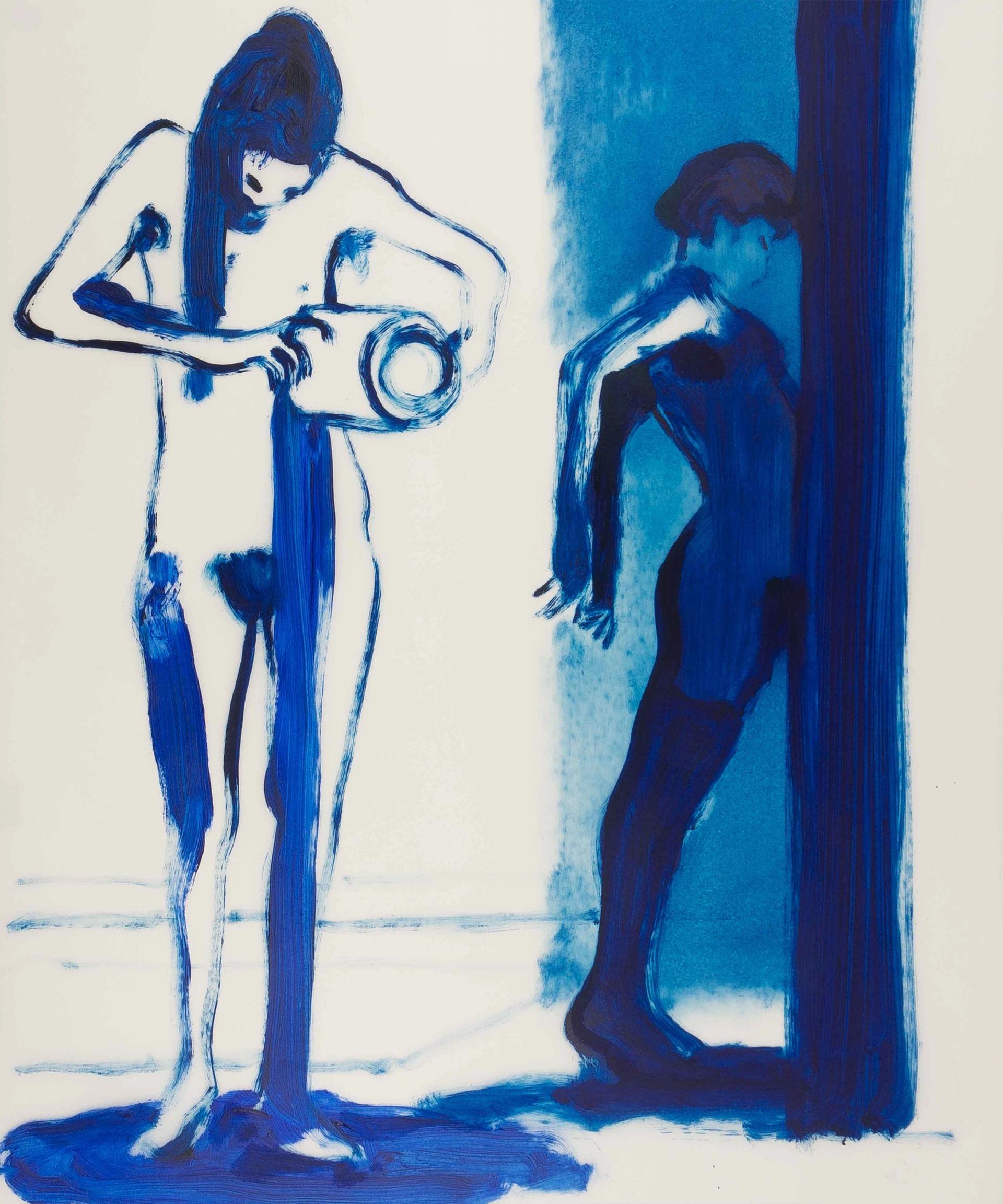

Lisa Brice's Untitled (2019) Copyright Lisa Brice. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photo by Todd-White Art Photography.

Risk taking was more common and less calculated in the early days. “I started with [emerging] artists such as Yinka Shonibare, David Shrigley, Mamma Andersson—in Mamma’s first show, the paintings were €3,000-€4,000 and now they’re $500,00-$600,0000, she’s in museums all over the world,” Friedman says. “We worked hard to build those artists’ careers.” But by the mid-2000s, as the sums escalated, Friedman’s risk taking became “much more calculated and strategic”. The British art buying public was growing, but still conservative in its tastes, so Friedman had to attract an international audience to his corner of Mayfair: “That’s how I really grew the business.” When several big US-based galleries—such as Pace and David Zwirner—opened outposts in sleepy Mayfair in around 2012, it “changed the game”. Many of his dealer colleagues feared such shiny upstarts would poach their artists and clients, but Friedman relished the competition: “It forces us to work harder, makes us present the best version of ourselves.”

He has “mixed emotions” over the pandemic-induced cancelation of fairs. They account for “a relatively large amount” of the gallery’s turnover, he says, but “there’s also a huge amount of money involved and a big impact on the environment which we’ve all become much more aware of recently.” The past few months, he says, “have been a tumultuous time and you have to have nerves of steel. We’ve had to find innovative ways to interact with our clients and stimulate demand.” Initially, after the UK was locked down in mid-March, Friedman felt the gallery should be respectful of its clients’ space. “But then I had a conversation with my team and said ‘look, this is not a time to stay away, it’s a time to really reach out to people’,” he says. So he wrote to around 100 top clients and suggested a private Zoom call—95% said yes: “I was amazed. What I was hearing from clients was that very few galleries had done this. This was not about trying to sell things—although on every call I had a few works at the back of my mind to discuss with them—it was really about keeping in touch with them.”

The 25th anniversary show includes several Latin American artists such as the Brazilians Luiz Zerbini and Tonico Lemos Auad, Juan Araujo from Venezuala and Manuel Espinosa from Argentina. This Latin American connection dates back to a year before the gallery opened, when Friedman started to travel to Brazil where he felt “an immediate affinity with the culture”—he still collects 20th-century Brazilian furniture—and became friendly with the dealer Marcantonio Vilaça, the founder of Camargo Vilaça Gallery in São Paulo, who he describes as “an amazing man, the first to promote Brazilian contemporary artists on an international scale".

Luiz Zerbini's Quadr í cula (2019) Copyright Luiz Zerbini. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photo by Pat Kilgore.

Vilaça would be amused by the suggestion he was a mentor, Friedman says, but he names two dealers who have been: Barbara Gladstone (“even before I opened the gallery, whenever I went to New York she always made time for me”) and Leo Castelli. As a teenager in Montreal, Friedman would read profiles of Castelli, the near legendary New York dealer, and dream of being an art dealer. Then in 1994, he was invited by a family friend who was on the board of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis to a weekend of art events at the museum to mark the opening of a Bruce Nauman show. When bundled into a taxi to go on a tour of collectors’ homes, he looked to his right to see he was sat next to Castelli: “We had an amazing conversation, I told him I was opening a gallery next year. We spent hours chatting over the weekend, he gave me a lot of advice. A weekend I never forgot.”

A quarter of a century later, what advice would Friedman give aspiring art dealers? “You have to have a consistently amazing eye, a strong head for business, the ability to balance commercial artists and less-commercial artists, those that are more experimental. And most of all you have to have the ability to build trust from the art community, through developing personal relationships.” That means “picking up the phone, not just barraging people with emails.” Furthermore, even if your name is above the door, as his is, Friedman believes “galleries should not be dictated by their proprietor. To be robust and sustainable, you need an open and empowered management team that respects everyone in the company.” You must, he thinks “trust each other to make decisions. Of course, we make mistakes, but we work together.”

And while Friedman thinks he’s an efficient networker—the sort who can get in and out of parties in half an hour, say hello to everyone he needs to, then home in time for supper—he is also good at making himself invisible. “I love standing on the side of the room, people watching, and I’m always amazed, in this business, by how seriously some people take themselves,” he says. An echo of the thoughts of many.