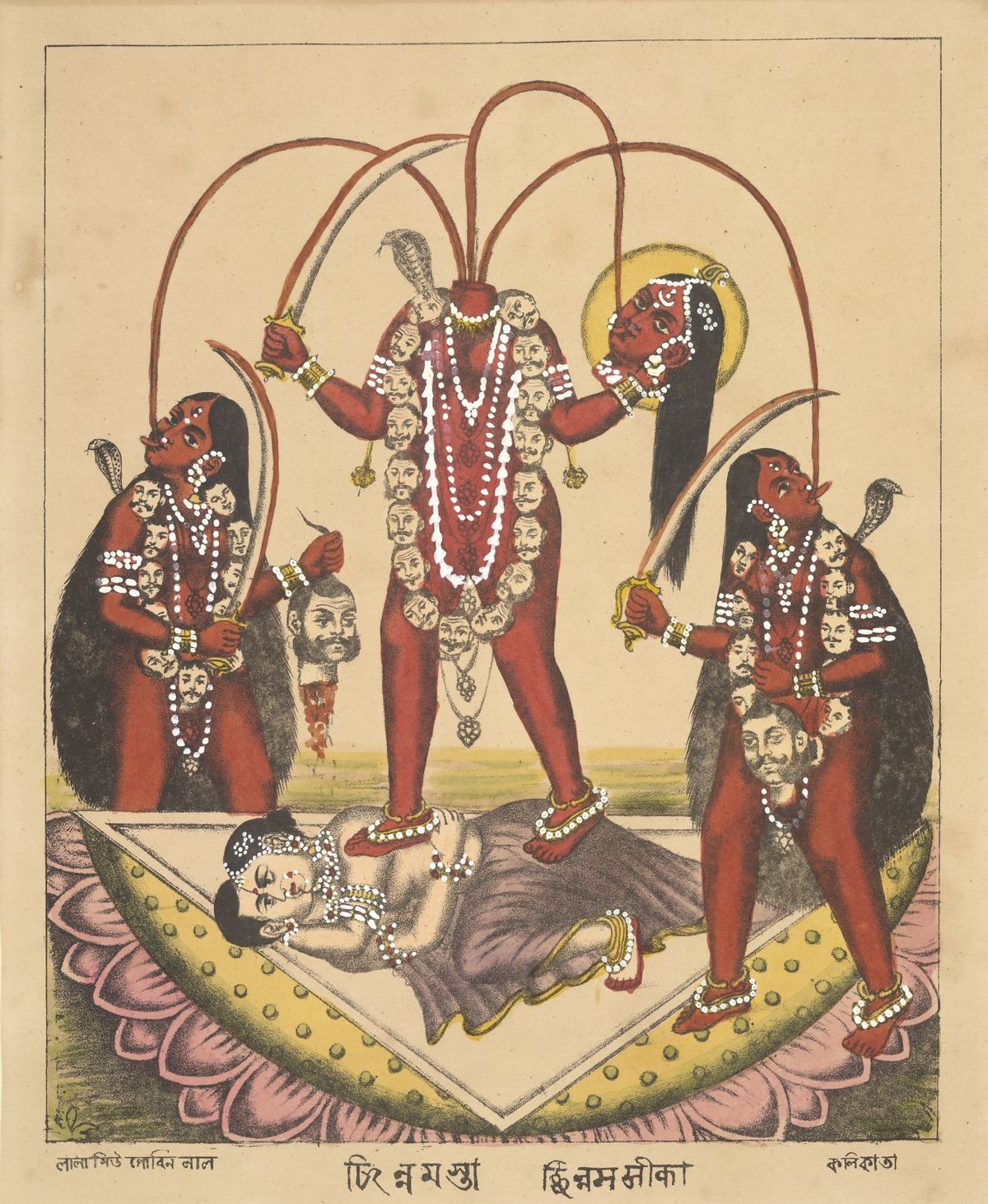

The tradition of Tantra, as we learn from a newly opened exhibition at the British Museum (until 24 January 2021), has always been transgressive. Obscene in every century, it emerged in India around 1,500 years ago in reaction to strict purity beliefs held by Hindus and Buddhists. Its first practitioners—evidenced by 6th century stone statues—carried human skull cups to symbolise the beheading of a Hindu god. This is everything your mother warned you about. Sex (countless depictions of couples in carnal embrace, attempting to harness primordial cosmic energy and achieve enlightenment); drugs (gorgeous Mughal-era paintings depicting yogis smoking from 18th-century bongs); violence (catch the goddess Chinnamasta and her necklace of severed heads); there is even rock n’ roll (turns out The Rolling Stones's famous outstretched tongue is modelled on the goddess Kali’s). By the 19th century, Tantra had become the face of Bengali resistance against the British Raj; in the 20th, global counterculture sought out its potent philosophy to rethink the politics of power, disgust and freedom. In a wonderful cross-cultural reference, Sutapa Biswas’s 1985 depiction of Kali shows her holding a flag loosely depicting Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith Beheading Holofernes (1614-18). Emerging from the show's narrative is Tantra's most powerful message, which states that the divine exists in our material plane. Liberation, we are told, can be found here on earth. But only if we are brave enough to seize it.

And while you’re at the British Museum, make sure to check out Edmund de Waal's Library of Exile (until 12 January 2021). Featuring more than 2,000 books from the British ceramicist and writer’s working library, this touching installation honours the bravery of authors who either fled their homeland or were persecuted within it. Loosely painted in liquid porcelain around the work’s exterior is de Waal’s “ode to lost libraries”, from Antioch to Alexandria. Written up high is a quote from the German poet Heinrich Heine: “Where they burn books, then they will burn people”. Unveiled at the 2019 Venice Biennale and then shown at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden, this is the work’s final destination before its contents will be donated to the University of Mosul, which is currently being rebuilt after attacks by Islamic State. As national borders the world over are increasingly fortified, this calm point of contemplation reminds us of the wonderfully transportive and revolutionary powers held within books.

Wham! The Brent Biennale has arrived (until 13 December), complete with a 9m-high George Michael mural by Dawn Mellor. One of London’s last corners yet to be invaded by the art world, it is somewhere actual community exists—most arrestingly in its libraries, now taken over by the likes of Imran Qureshi, whose imposing installation And they Still Seek Traces of Blood spatters enormous paper forms with red paint like a crime scene. Meanwhile Karachi-born, Cricklewood-based Rasheed Araeen invites visitors of Willesden Green Library to arrange and move his trademark lattice cubes around at will giving them an anarchic, as well as an orderly, presence. After all, you are not meant to mess with Minimalist sculpture and certainly not in a library. More sombre is Ruth Beale’s memorial to Covid-19 victims. Brent—one of the most diverse areas in the country—was also the worst hit during the height of the pandemic. In honour, Beale has placed bookplates in 491 carefully selected library books: one for every victim of coronavirus in the borough up to September 2020. The public are then invited to choose a book and add a dedication for anyone they know who has died. The books, which come from libraries across Brent, will then be redistributed throughout London.