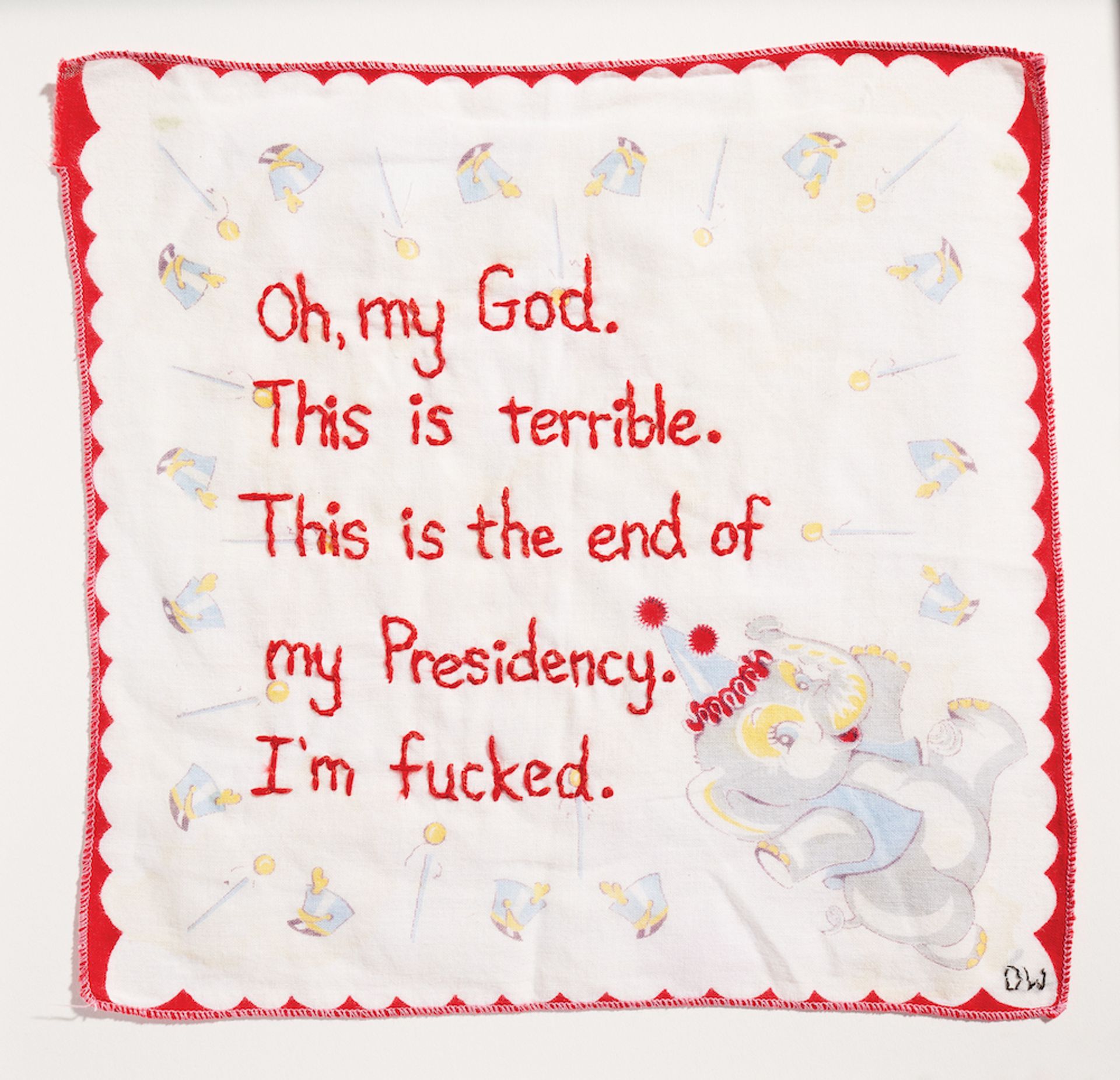

It was two years into Donald Trump’s presidency when Diana Weymar decided to finally engage with his notoriously inflammatory posts on Twitter. But instead of using Trump’s social media platform of choice, Weymar, a textile artist, chose alternative media: needle, thread and vintage fabric. Her ironic interpretations of the US leader’s most memorable statements will now go on view in a series of exhibitions ahead of the presidential election in November.

“My two greatest assets have been mental stability and being, like, really smart,” Trump tweeted in January 2018 in response to the release of Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House, the journalist Michael Wolff’s book criticising his administration. Trump concluded by describing himself as “a very stable genius”—a statement Weymar felt compelled to satirically stitch onto one of her grandmother’s floral needlework projects. When she posted a photo of her completed piece to Instagram, the positive response encouraged her to embroider more of Trump’s statements. Once she started making them, she could not stop.

“If he says something and I stitch it, how do you see it differently?” Weymar says. “My feeling is that if you can stay present long enough to read what he’s saying, you will become politically active. You will feel a sense of urgency.”

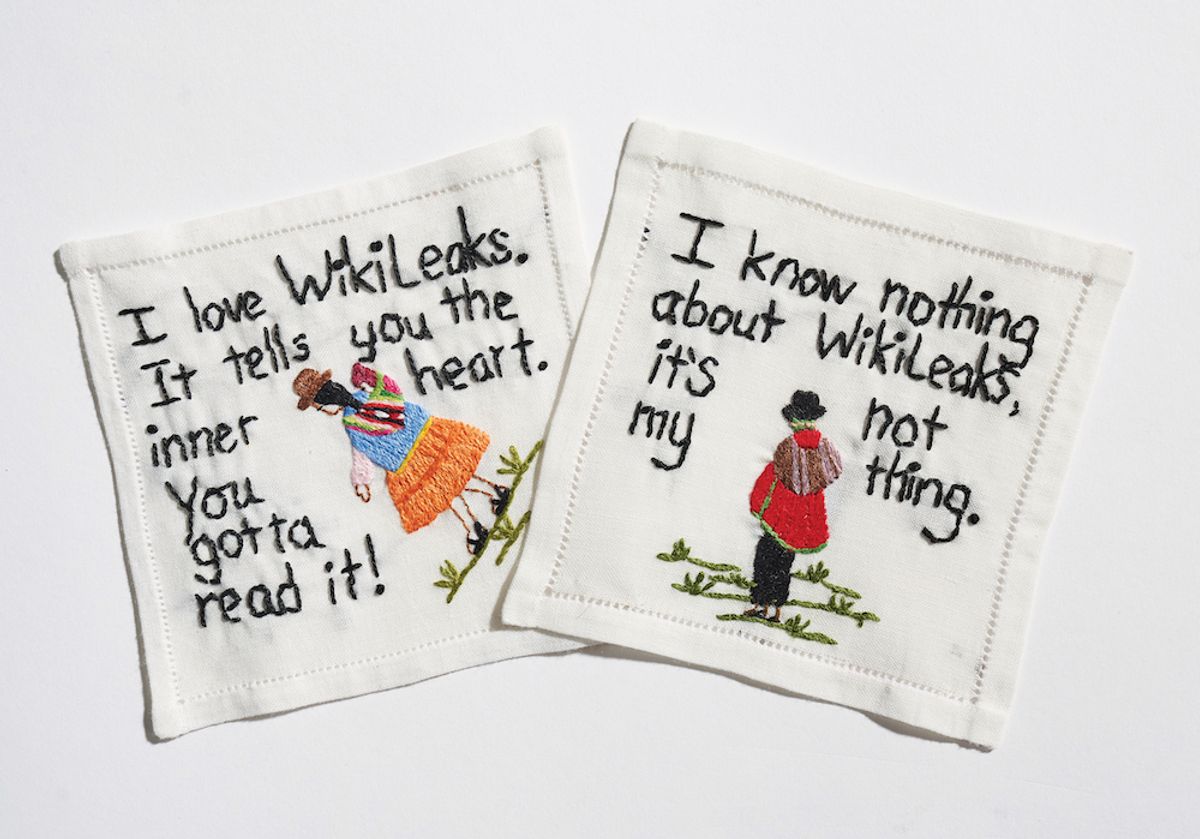

Within months, Instagram followers around the world asked to join Weymar in embroidering excerpts from Trump’s tweets and speeches. Others contributed charged fabrics such as handkerchiefs that belonged to Holocaust survivors, and the bedsheets of same-sex couples. Though Weymar originally conceived of this as a solo undertaking, the volume that she hoped to record led her to embrace this as a group effort. “Individual protest is quite a different thing than collective protest,” Weymar says. She now envisions the initiative as a digital march that currently contains more than 3,500 embroidered protest signs.

The Tiny Pricks Project at Culture House in Washington, DC will display embroidered tweets related to a variety of societal issues Photo: © Nelson Hancock, courtesy of Tiny Pricks Project

Dubbed the Tiny Pricks Project, it aims to “create the material record of [Trump’s] presidency and of the movement against it,” following in the footsteps of other collaborative textile projects, such as the Aids Memorial Quilt. The sharp contrast between Trump’s words and the resulting, stereotypically feminine works is part of their allure. Tweets can be carelessly written and easily deleted; embroidery is more permanent and requires time and skill.

As the US presidential election in November draws closer, Weymar has deliberately arranged to exhibit the works. A couple of hundred pieces related to climate change are on view at the Bateman Foundation in British Columbia, Canada, while others about sexual violence are in a recently opened group show at the Beacon Gallery in Boston. In September, six works will be included in Never Done: 100 Years of Women in Politics and Beyond, a group exhibition celebrating the US centennial of women’s suffrage at Skidmore College’s Tang Museum. Another selection will be on view at New York’s Planthouse gallery in October.

And from early September through the end of 2020, the Tiny Pricks Project will wallpaper the gallery at Culture House in Washington, DC—a nonprofit exhibition space in a converted and historic African American church. Culture House is only two miles from the White House, and the intentionally located solo exhibition will address themes such as racial and economic justice, and environmental preservation.

If Trump is re-elected, the Tiny Pricks Project will likely maintain its current format; if he is voted out, revelatory accounts about his administration may loop in Photo: © Nelson Hancock, courtesy of Tiny Pricks Project

“Our hope is that visitors will find [the project] to be both thought-provoking about how our culture has reached this moment, and motivate them to work to improve our politics and our communities,” says Zachary Levine, the art director of Culture House. “What do we anticipate the response will be? Amusement and, we hope, motivation to action.”

Weymar still is not sure what will become of her project after the November election, but she has some ideas. If Trump is re-elected, it will likely maintain its current format; if he is voted out, revelatory accounts about his administration may loop into the project. Ultimately, though, Weymar plans to keep the growing collection as a whole and make it publicly accessible. “I want to have all of the pieces together,” she says, “where people have the opportunity to see the entire scope of the project.”