"Hockney Unlocked" is a series of 80 short films produced, directed and edited by Bruno Wollheim. The films are outtakes from Wollheim’s award-winning documentary, "David Hockney: A Bigger Picture", filmed single-handedly over five years with David Hockney. Here, Wollheim writes a commentary on some of the short films informed by a friendship stretching back 30 years.

This video needs some little unpacking. It must be galling to believe you have made a ground-breaking discovery in the history of Western painting, only to be labeled an eccentric and find art history marching on regardless.

In this clip from 2008, David Hockney’s situation was unchanged, a prophet in the wilderness. His book and film Secret Knowledge had come out seven years before. It had argued that lenses and mirrors were in widespread use and had revolutionised the look of Western painting for at least 500 years before the invention of chemical photography in the 19th century, when a projected image could be permanently fixed. Hockney was convinced that from the Early Modern era onwards, the West had been in thrall to a photographic way of seeing—and that these ties that bind painting and photography together are so close and enduring that we have become blind to them and hardly know they exist. Like shadows.

David Hockney drawing with the the aid of a camera lucida (1999) © Phil Sayer

It was particularly the study of Chinese art that opened Hockney’s eyes to what had happened in Western painting. His first visit to China was in 1978 with the writer Stephen Spender, resulting in their illustrated China Diary (1981). A film made with Philip Haas followed in 1987, called A Day on the Grand Canal with the Emperor of China, contrasting two 17th-century cityscapes, one from a Chinese scroll by Wang Hui and one by Canaletto, a view of the Grand Canal in Venice.

Chinese painting had also been a crucial influence on Hockney’s painting of the Yorkshire landscape. I had just been filming him from up a ladder with his facsimile of a 17th-century Chinese scroll. He had been demonstrating how the Chinese principle of moving focus could better capture our experience of space. With no fixed vantage point, as distinct from Western linear perspective, the eye is free to move through the landscape.

Now he was on to shadows. Did the Chinese not see shadows or at least not register them as important? Is it the camera that makes us see them? Can you choose not to see them? Thought-provoking stuff. David likes nothing better than to confound our hard-wired assumptions about perception.

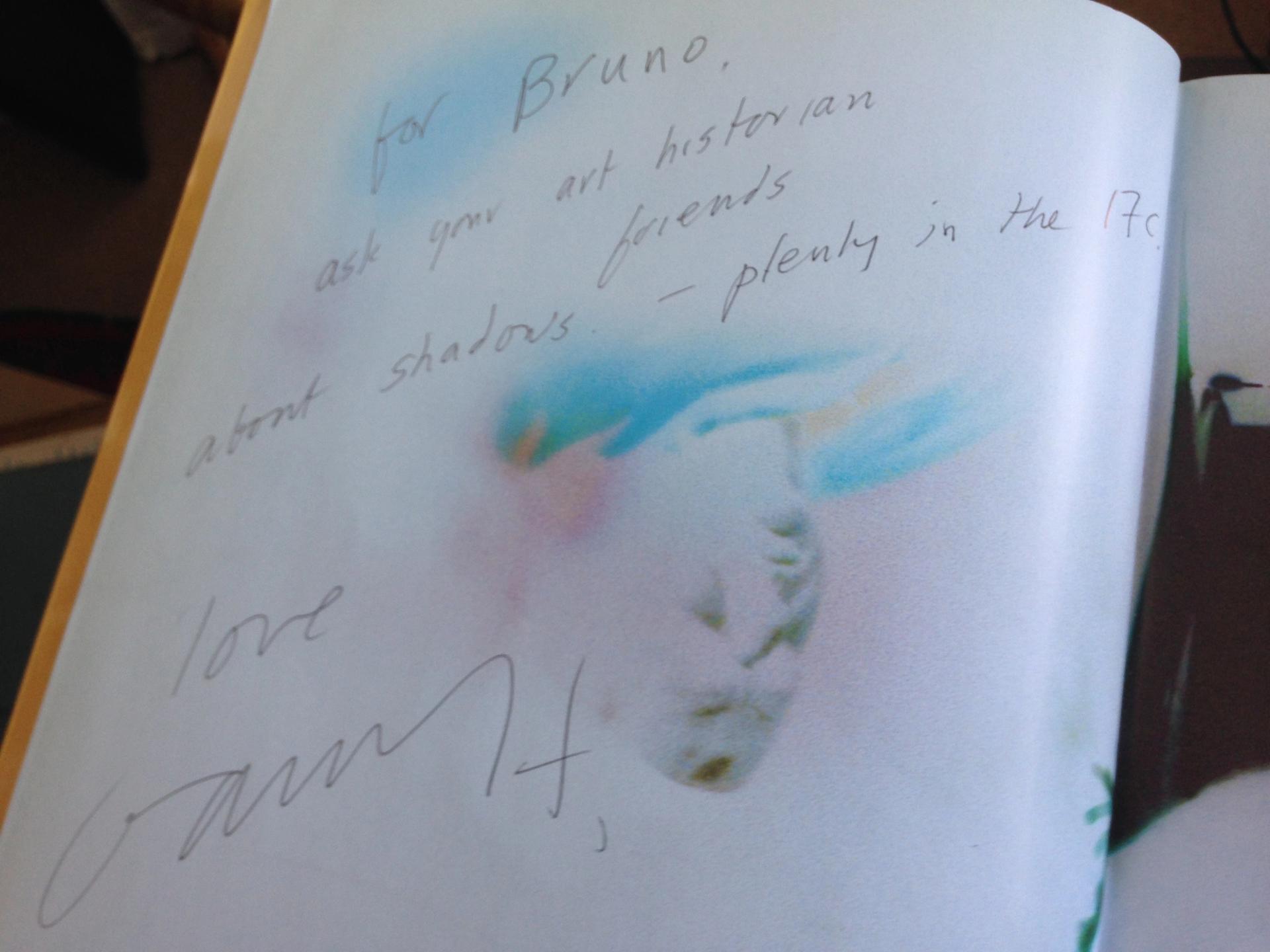

David Hockney's inscription which reads: "For Bruno, ask your art historian friends about shadows—plenty in the 17c. love David H."

From there, it was just a short skip and a jump to the quintessentially proto-photographic images of Caravaggio, or, as David puts it, the arrival of Hollywood lighting. While there are still ardent opponents (foremost among them, Andrew Graham-Dixon), recent research supports Hockney’s hypothesis: that, in Rome at least, Caravaggio had rigged up a sort of camera-booth cum studio, with holes in the ceiling for natural top-lighting, and used mirrors and lenses to project a cast of actors with their props directly on to his canvasses. How else to explain the guide-marks in the underpainting and the absence of preparatory drawings for such complex compositions? A superb mastery of photographic technology was behind Caravaggio’s revolutionary use of chiaroscuro.

Hockney’s own embrace of high tech gizmos—from the Polaroid, the Xerox, the Fax, the Quantel Paintbox, the iPhone and iPad, to high-definition cameras—must have helped shape his thinking. The opprobrium that was heaped on Secret Knowledge from many art historical quarters had something similarly personal: that Hockney was projecting his own technical inadequacies on to the Old Masters, demeaning their technical mastery to conceal his own, and reducing them to crude copyists.

Hockney is an autodidact and no scholar. He was working intuitively from visual clues and anomalies he had observed; these empiricist methods undoubtedly led to some exaggeration, a lack of nuance and some technical errors. Above all, his critics argued that such a prevalent use of new technology would have left a much larger documentary trail, especially in first-hand accounts of the practice. For them the secrecy of the knowledge did not wash.

I believe the main thrust of Hockney’s thesis will be vindicated: that the emergence of proto-photographic technology lies behind the staggering leap towards greater verisimilitude and naturalism in Florentine and Flemish painting from around 1420, which went hand in hand with the more coherent use of shadows, and that this was further developed and refined by the likes of Caravaggio, Vermeer and Velasquez. Also that this use of technology in no way diminishes their achievements or greatness. All the artists and painters I have met agree with Hockney, and view the ad hoc short cut a technology can supply as just plain commonsense.

Hockney’s project pretty much filled up the two years that followed his mother’s death. It convinced him to swim against the photographic tide and go back to the primacy of painting and drawing by hand. It also convinced him that critics and art historians had little to no interest in how art gets made. It was also responsible for the filming access David gave me up in Yorkshire, since my filming him at work would become a de-facto demonstration of the superiority of painting over the photographic. And as an ex-Harvard scholar and art history graduate student, I was fair game: “Ask your art historian friends”, he would josh, when he found some inaccuracy or worse, a lack of curiosity.

Fra Angelico and Piero della Francesca represent for David the pinnacle of Old Master Italian painting—the light that comes from within. Nevertheless, however many light years separating their sensibility from Caravaggio’s, I will never forget going with David in 2006 on a private night-time visit to The National Gallery’s exhibition Caravaggio: The Final Years. The mechanics do not alter the majesty.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fpd5X0B5qm8

• David Hockney: A Bigger Picture is now available online