When the Yale Center for British Art announced last year that it had recruited Courtney J. Martin as director, some were surprised that she was making the leap from her post as deputy director and chief curator at the Dia Art Foundation in New York. Like Dia, Martin specialises in art of the 1960s and 1970s, whereas the Yale museum—in New Haven, Connecticut—is better known for paintings by august British masters like Gainsborough, Constable and Reynolds that were collected by its founding donor, Paul Mellon. Yet Martin and her colleagues are busy making connections between historical works and contemporary art as the centre gears up to reopen this autumn.

She tells The Art Newspaper about her goals for the museum as well as her thoughts on diversity and outreach amid the Black Lives Matter protests. Here are some excerpts from the interview.

The Art Newspaper: What attracted you to the job at Yale?

Courtney J. Martin: My attraction to the job goes back a long time. When I came to Yale to work on my dissertation, the centre held so much for me. First of all, it is in this amazing building. It is [Modernist architect] Louis Kahn’s last building.

I came to Yale wanting to do something very specific. I wanted to work on British art after ’68. Most of the artists that I was working on at the time were living and were, I would say, under-recognised by the art world and also by the history of art.

One of the things that working at the Dia Art Foundation instilled in me is that if you are the chief steward of a collection, the living artists in your collection should also be known to you. I have been working on that at the centre now. We have a pretty small number of living artists in our collection relative to other museums of our size.

Did you set any specific goals for yourself when you took over as director?

Yes: learn the collection. I knew it as a student, but there was a lot of collecting and exhibitions that happened between when I left in ’09 and the present, so I had a lot to catch up on.

I wanted to become more knowledgeable about Kahn because I have to take on the responsibility of this building.

Inside the Yale Center for British Art, designed by Louis Kahn and completed in 1977

The last big goal I have is that we suffer from invisibility as a museum. I think that people see us as a research institute and sometimes forget that we are a museum. If I can do anything in the next few years, it will be to make people know more about what we offer them as a museum.

Do you come up against the US stereotype that British art is all about Turner and Constable?

I do, but I would say that I have to do that with almost everybody, including British people. But I also think that I work really hard to make sure that people see the contemporary artists in line with their predecessors because we offer this huge sweep of art from the late 17th century to the present that makes sense of some of the things that we are doing now.

The museum has been closed since mid-March because of the Covid-19 pandemic. When do you hope to reopen?

We are hoping that we will reopen early this fall. We’ll only be open a few days a week, which will allow us to control the numbers. Smaller numbers but sustained visits—I hope that that will work.

The US has been gripped by the Black Lives Matter protests in recent months. Does the centre have a critical role to play in advancing racial justice? In a statement, you said your team was “looking for ways to take action that will, over time, bring change to our institution”.

I would say that as individuals, every single person can do what he or she is able to do. As an institution, I think that we can work towards making our collections known to people and welcoming to all.

From our mission, we have a substantial amount of funds set aside for education. New Haven is not a wealthy city. Our focus for the coming months should be to double down on how we best offer our collection, resources and our time, to the children of this city so that they have a cultural outlet, even if they do not have a regular school day in the coming year.

Aside from your appointment, has the museum hired and promoted black curators and administrators? You told the Independent newspaper that leaders should cultivate their successors. Do you believe that the museum sector has to catch up on racial diversity?

The museum sector is not alone in being at a lag for not just racial diversity, but also gender and economic diversity. If every director, even in this country, went out and looked among the ranks of the workers in his or her own institution and gave equal time to a broader range of people, we might have a very different workforce. I think that mentorship has often been given out very freely to certain people but not to everyone. There are ways to do it and not ways I think that would tax anyone. But we have not made any significant hires since I arrived, largely due to the quarantine. We are also under a hiring freeze.

I would also say diversity isn’t the measure by which I would actually count for our success. Are we serving everyone equally? Do we bring in objects and people to those objects that feel as if they belong in our spaces? Those are bigger questions that we need to interrogate.

Are you trying to bring more artists of colour and international artists into the collection?

We have always historically had a large percentage of international artists. Mr. Mellon was ahead of his time, but he was also a product of empire. The countries that Britain formerly colonised were also the countries from which he found his collections. So we have large collections of works from the South Pacific, Africa, Asia and specifically from the continent of India. Most of them pre-date the 20th century.

We are not a contemporary museum. My goal is not to change the fabric of the institution. We are the collection of Paul Mellon. This is where we come from and, in many ways, everything that comes after that responds to those initial objects in the collection.

We have a painting in our collection that was not a Mellon object. It was a gift that shows one of the founders of Yale, Elihu Yale, within a group portrait with an enslaved child. That painting has been a cause of a lot of criticism and concern. I think one of the best ways that we deal with this is to talk about it and to make our process known to other people.

1708 painting by an unknown artist depicting Elihu Yale, one of Yale's founders, within a group portrait that also features an enslaved child Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Andrew Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire

Lucky for us, the artist Titus Kaphar, who is a resident of New Haven, has made a painting that references the Yale painting. In 2016, he finished Enough About You, and instead of the group portrait, the servant child is the subject of the painting. We plan to bring that painting into our space to be in dialogue with its reference so visitors can understand how you work with history, even when that history is troubling and problematic.

Titus Kaphar, Enough About You, 2016 Courtesy of the artist

Last year, you said that one of your priorities would be to “reposition British art within a global framework of migration and cultural exchange”. Can you elaborate on this?

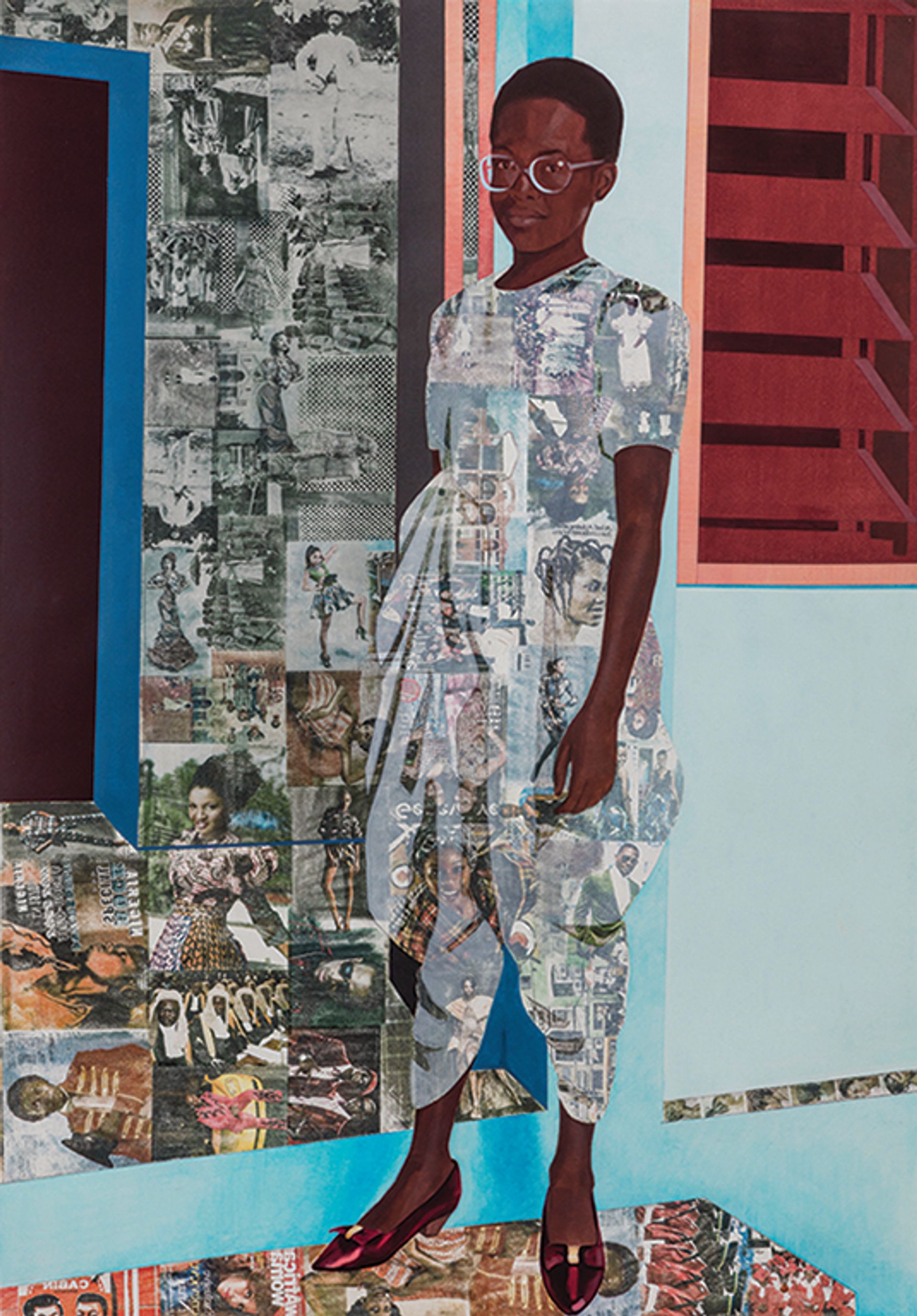

Bringing in Titus’s painting is a perfect example of doing that. We are also embarking on a programme where we will invite filmmakers and moving image artists into our institution to talk about and show their work. We are also working on an exhibition with Njideka Akunyili Crosby, which we hope will open in January. Njideka is a 2011 graduate of the Yale School of Art. We have long been interested in working with her. But this has given us a real chance to see her work in the context of a larger understanding of British portraiture.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, The Beautyful Ones Series #1c, 2014 © Njideka Akunyili Crosby; courtesy of the artist, Victoria Miro and David Zwirner

You are also planning the show Love, Life, Death and Desire, juxtaposing Damien Hirst’s work with historic art in the collection. What dialogues will it start?

The exhibition has a good deal of late 18th- and early 19th-century group portraits and landscapes, as well as solo scenes of lovers but also of people who were just in loving contact. There are works by [Henry] Fuseli and Angelica Kauffman and Joseph Wright of Derby and Anthony van Dyck. But it is not so much that Hirst is being juxtaposed against them—they are all within an immersive environment looking at love and lust. I think that often as contemporary people, we are limited; we cannot immediately look at a painting that is outside of our time and recognise its resonance. But this is exactly what the show hopes to achieve.

Angelica Kauffman, Rinaldo and Armida (1771) Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Tell us about your upcoming Bridget Riley exhibition.

Bridget Riley is an artist whose work I have known for longer than I can remember and just thought it was so incredible. It has been a delight to begin getting to know her.

She is embarking on the first revelation of her relationship to America. She first came to America in 1965 to participate in the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, The Responsive Eye, that is seen as bringing optical geometric-based abstraction to American viewers.

She had a kind of fairytale trip, and that started a lifetime engagement with those artists and collections. She really began travelling after this period. But she looks back on that moment as being one that really raised the stakes of her career. And I think that she wants to use this show to explore that.

All of the works in the exhibition are her selection. It is Bridget’s show. We are here to assist her. That's something I learned at Dia. I think that if you are having a conversation with an artist about an exhibition, they should lead that conversation. They made the art. It makes sense that they would know what should happen with it.