Although integral to the economy, represented on the Supreme Court and a vibrant force in American culture, the nearly 60 million-strong Latino population in the US is often overlooked in the narrative presented in the nation’s museums, many argue.

The Latino presence in America dates to well before the arrival of British settlers, stretching back over 500 years, and it is expected that Latinos will make up as much as a third of the US population by 2060, up from nearly a fifth today. But exhibition programming highlighting their contributions has been woefully deficient, lawmakers and scholars say, ignoring that they are active participants in every walk of life as artists, veterans, athletes, jurists, business leaders, scientists, doctors and service workers.

The US House of Representatives has taken a major step towards rectifying that imbalance, moving in a voice vote on 27 July to create a National Museum of the American Latino that would rise on the National Mall under the umbrella of the Smithsonian Institution. Now a companion bill awaits action in the US Senate when it reconvenes this month.

Sonia Sotomayor, the first Latina justice on the US Supreme Court Steve Petteway, Collection of Supreme Court of United States

The House bill, introduced last year by Democratic Representative José E. Serrano of New York, drew 295 co-sponsors and broad bipartisan support in the 435-seat Democratic-majority chamber. Advocates are now lobbying to muster backing in the 100-seat Senate, where 51 votes are needed for passage and 43 co-sponsors have been enlisted so far, according to Estuardo Rodriguez, the president and chief executive of the nonprofit Friends of the National Museum of the American Latino.

“Sixty-seven is a magic number for us,” he says, referring to the co-sponsors his organisation hopes to recruit. Bipartisan support will again be crucial: the measure was introduced by a New Jersey Democrat, Robert Menendez, and the Senate has a 53-member Republican majority. Rodriguez says he hopes momentum will build in anticipation of the start of Hispanic Heritage Month on 15 September.

Hispanic heritage

The consensus that Latinos are underrepresented in museum programming dates back to at least 1994, when a Smithsonian task force issued a report stating the institution displayed a pattern of “willful neglect” and “almost entirely excludes and ignores Latinos in nearly every aspect of its operations”. The legislative push to establish a fully-fledged museum began in 2003 but then faltered.

Lawmakers approved a bill to create a commission to study the possibility in 2008, and the panel issued an in-depth report in 2011. Subsequent legislation to create the museum never won passage, but lawmakers revived the campaign with the introduction of the House and Senate bills last year.

If the Senate passes the bill and it is signed by President Trump, a board of trustees for the museum will quickly be formed and fundraising will begin in earnest, says Danny Vargas, the chairman of the Friends’ board. He says that four sites are currently under consideration on the National Mall.

Four sites are currently under consideration on the National Mall for the proposed museum

The legislation calls for the new museum to forge a narrative illuminating the contributions of Latinos to US history and culture by forming a collection, organising exhibitions and events, and championing research and publications while collaborating with other museums and cultural centres across the country. “There is such a need to tell the Latino story,” says Rodriguez. “The media, Hollywood, politicians—everyone presents their version of who the Latino American community is. An accurate narrative is vital for every American.”

A fuller accounting could also help counter prejudice in an era when even the nation’s president has railed against Hispanic immigrants.

Rodriguez notes the recent one-year anniversary of a mass shooting by a Texas man who targeted Hispanic shoppers at a Walmart store in El Paso, killing 23. “That man was driven by not just hatred but also an inaccurate understanding of our history,” he argues. “The fact that he believed there was an invasion [of immigrants] happening showed he had no understanding of that region of our country, the Mexican American footprint, and how it has always been, dating back hundreds of years.”

Campaigners estimate that $700m would be needed to establish and construct the museum, hire its staff and create its initial programming. The legislation calls for half the funds to be provided by Congress and half by donors.

But organisers are mindful that it took a massive, decades-long effort to create the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which has proved highly popular since it opened in 2016. “Many who donated to the African American museum have reached out to us and said: “How are things going? Are things on track?” Rodriguez says. He says that campaigners already -anticipate funding pledges from -companies including Target, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo if the Senate bill is approved.

A separate proposal, approved by the US House in February, calls for the creation of a Smithsonian American Museum of Women's History, whose fate could be linked to the drive to acknowledge the underrecognised encapsulated in the Latino museum bill. The Senate version of the women's history initiative also awaits action.

In search of trustees

The legislation to create a Latino museum calls for the creation of a board of trustees, with most of its members appointed by the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, and for a director to be appointed by the secretary of the Smithsonian, Lonnie G. Bunch III, who was the founding director of the African American museum. Much of the museum’s staff would have joint positions throughout the various other museums and research centres of the Smithsonian under the legislation’s current terms.

“If Congress were to pass legislation, and if the president were to sign the bill, we would embrace a museum dedicated to Latino art, history, culture and scientific accomplishments,” the Smithsonian said in a statement. In the interim, it emphasises that it has “made a concerted effort” to expand its representation of Latino Americans, adding 11 Latino content experts since 2010. The Smithsonian also notes that it has a department known as the Latino Center, which was created in 1997 and plans to open its first permanent gallery space at the National Museum of American History in 2022.

If Congress were to pass legislation, and if the president were to sign the bill, we would embrace a museum dedicated to Latino art, history, culture and scientific accomplishmentsSmithsonian

A 2018 report by researchers at the University of California at Los Angeles, however, judged that the Smithsonian had failed to ensure Latino representation in its governing and executive ranks since the 1994 “Willful Neglect” study and had neglected to develop a firm plan for Latino inclusion in the institution as a whole. And it found that funding for Latino initiatives and the Latino Center had been stagnant, essentially decreasing by 39% since the mid-1990s, when adjusted for inflation.

Stephen Pitti, a Yale professor who is a historian of Latino communities in the US, suggests that the proposed museum’s narrative should not be sugar-coated. “I think you would have to start with the hard stories, the violent stories, the disenfranchisement and slavery and genocide that are the beginning of all American history, as well as the celebratory stories” honouring prominent Latino individuals, he says.

Pitti points to two places on the American map as a potential starting point, Puerto Rico and New Mexico, which both had important Indigenous communities when Spanish colonisers arrived in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, and then experienced slavery. “Both are also touched by the age of revolution and changed by warfare in the 18th and 19th centuries,” he adds.

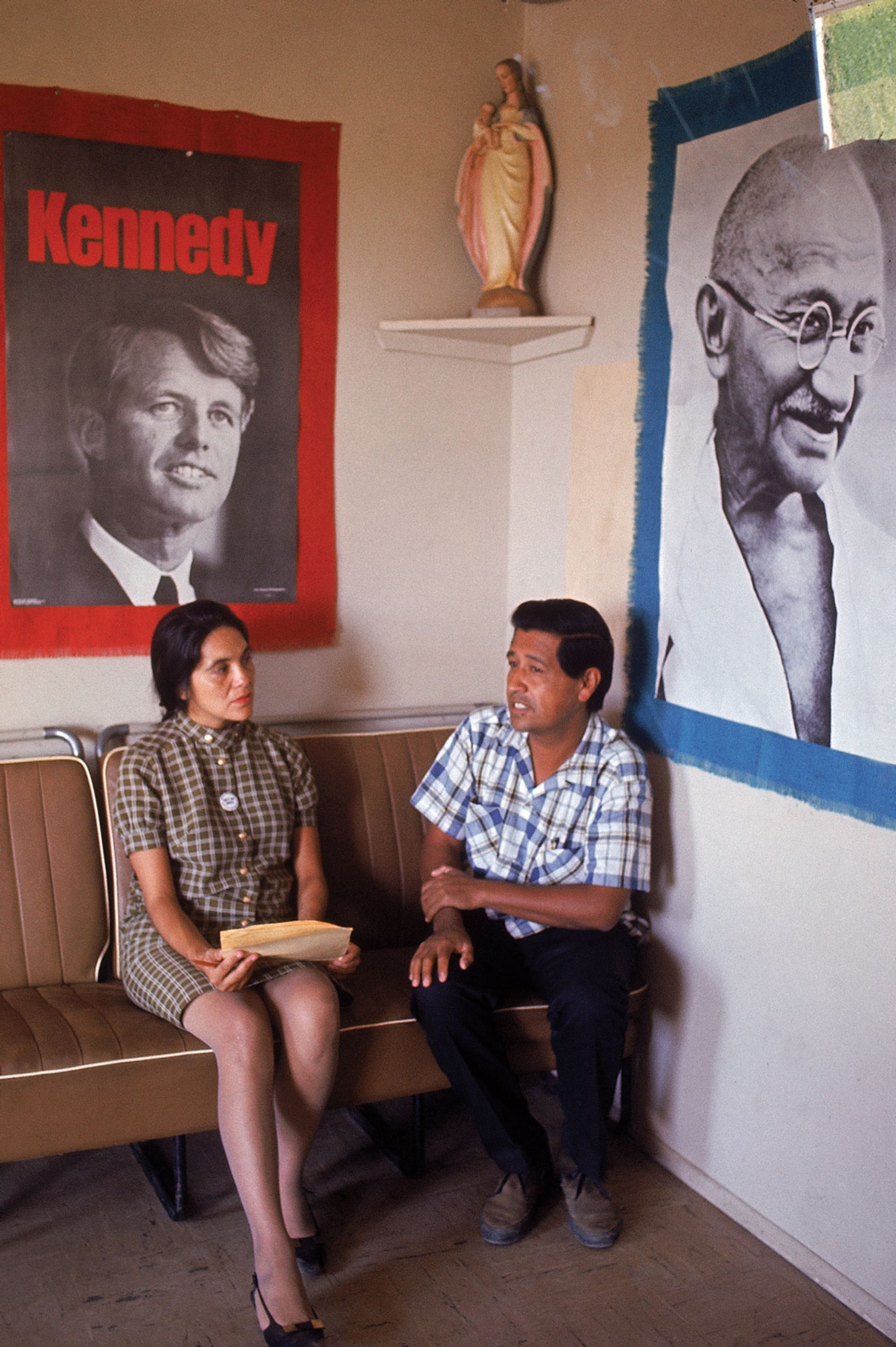

United Farm Workers’ leaders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez Photo © Arthur Schatz/LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

The museum could also illuminate the role of Latinos in the Civil War and the Second World War, Pitti suggests, delve into their economic importance in the history of gold, silver and mercury mining in North America, and explore their contributions to shaping leisure pursuits such as baseball over the past 100 years. Also critical, he adds, are Latino migration stories, shedding light on how religious, culinary and other cultural practices changed as people moved from their original home countries to New York or Arizona or California, and in some cases later moved back.

“There are artefacts related to these transnational stories—objects that reflect multiracial histories of conflict and resolution, musical instruments that show multiracial connections between African and Latino communities, business ledgers of Latino business owners in New York and San Francisco that sold food to diverse clientele,” he says.

It will be a major challenge to incorporate the many ethnicities involved, Pitti notes. “But it’s the same challenge most big ambitious museums face in the 21st century.”