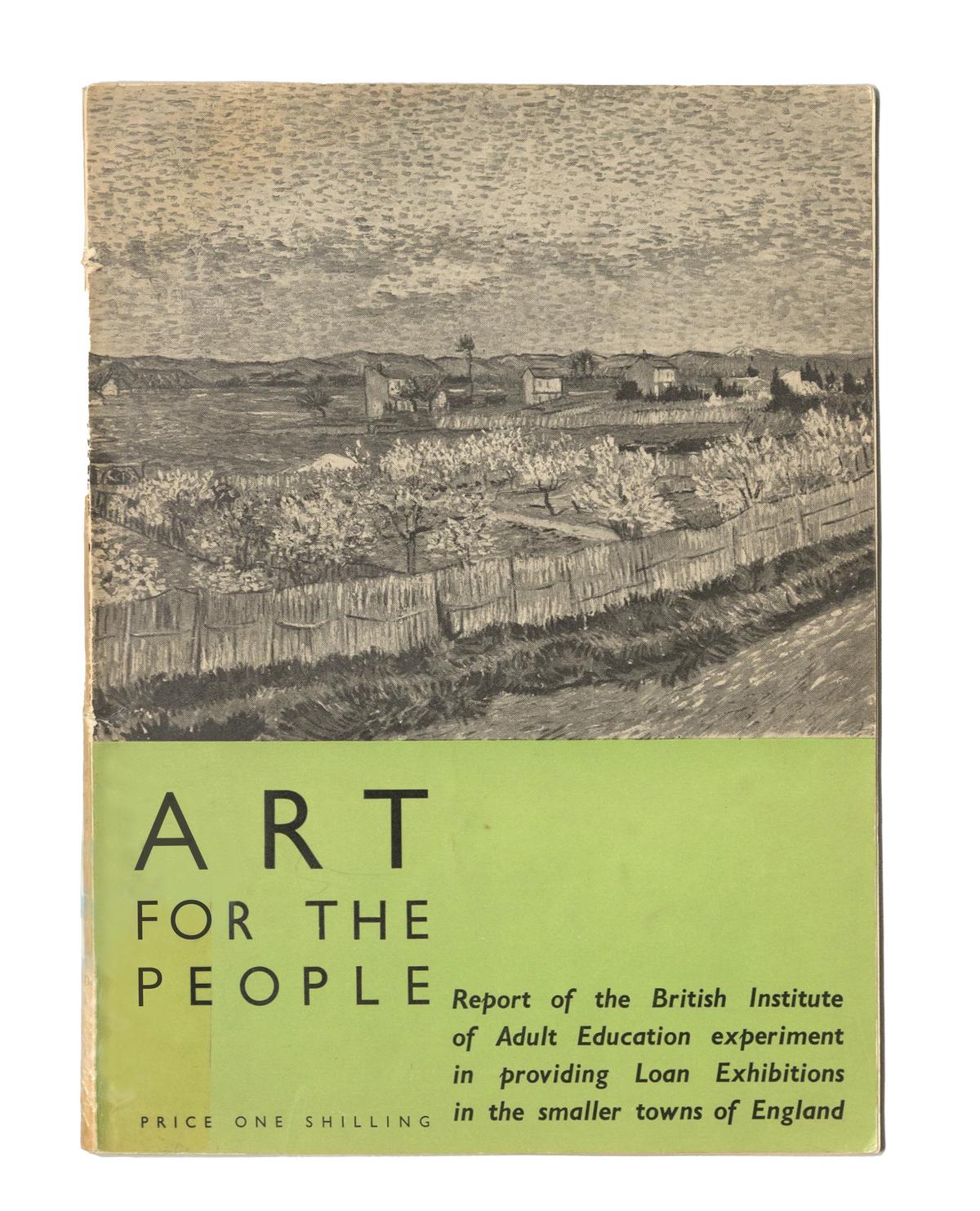

“Art for the People” might sound like a contemporary idea, but nearly a century ago it was the slogan of a pioneering experiment in the UK. Samuel Courtauld gave his blessing to the scheme, lending Van Gogh’s Peach Trees in Blossom (1889) to the village hall in Silver End, Essex.

Nick Serota, now the chairman of the Arts Council England, regards this pathbreaking project and the loan of the Van Gogh as one of the events that eventually led to the creation of his own organisation—and national museum programmes to lend to the British regions.

Painted just three months after Van Gogh mutilated his ear, Peach Trees in Blossom (1889) is one of his finest landscapes. A year after his death it was bought by the Belgian artist Anna Boch, who had earlier been the only known purchaser of a Van Gogh during the artist’s lifetime. Courtauld acquired the painting in 1927 for £9,000 (£500,000 in today’s money).

Vincent van Gogh’s Peach Trees in Blossom (1889) Courtesy of Samuel Courtauld Trust, Courtauld Gallery, London

The rationale for “Art for the People” was explained in a report by the organiser, the British Institute of Adult Education: “Most of the smaller towns of England have no art gallery and their inhabitants rarely have the opportunity to look at works of art.” The 1930s project involved sending exhibitions of loaned paintings from private collections to places without their own galleries or museums.

The Etruscan Room, Home House, London (1932) Photo: Eileen Harris © Country Life / Bridgeman Images

Samuel Courtauld was a generous supporter of the scheme. Peach Trees in Blossom, flanked by three small Seurat oil studies, normally hung just above the mantlepiece in the Etruscan Room of his grand London mansion, Home House, in Portman Square. In the early 1930s the room had served as Courtauld’s study, so he would have been only too aware of the temporary loss of one of his favourite Post-Impressionist paintings.

The British Institute of Adult Education wanted to send the loans to a truly rural village, but not surprisingly it proved challenging to find a venue that was “both suitable and safe”. In the end Silver End was selected. As the institute explained: “In one sense it fell short of the ideal choice”, since it is “not truly rural; it is a village diluted with industrialism”. But it did have one crucial advantage: a recently built (1928) and imposing village hall “which serves admirably for such purposes as that of an exhibition”.

Village Hall, Silver End (late 1920s) Courtesy of Silver End Heritage Society

Silver End is a village just outside Braintree, 40 miles north-east of London. The settlement was built in the 1920s to house workers from the nearby Crittall factories, run by the first company to manufacture steel window frames. It was a utopian “new” village, complete with a Modernist hall with a library, billiards room, theatre/cinema, dance hall and community facilities. At the time it was dubbed “the City of AD 2000”.

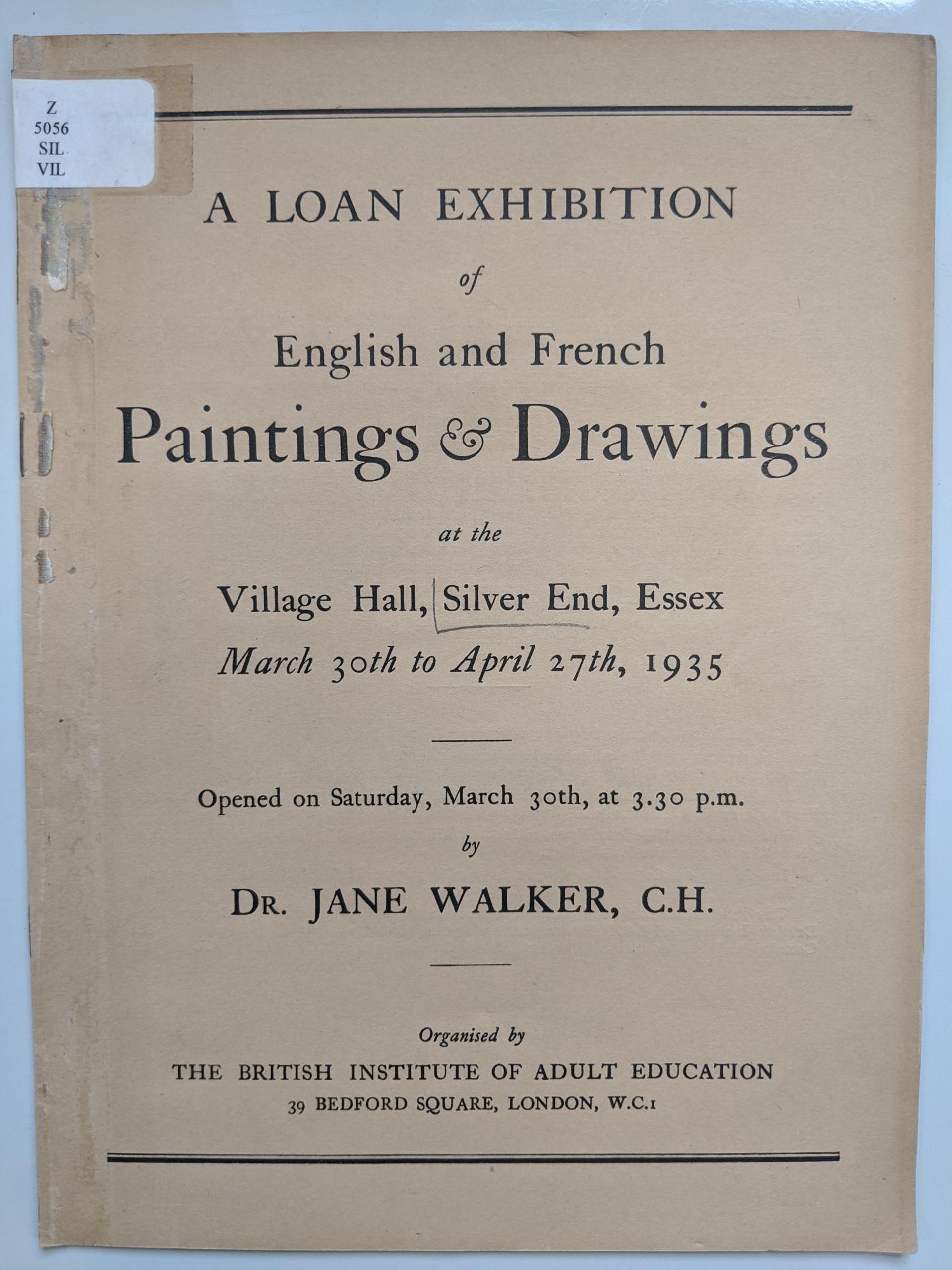

Entitled English and French Paintings & Drawings, the art exhibition was arranged in conjunction with the local branch of the Workers’ Educational Association. The show comprised 96 works, ranging from the 1880s to the 1920s, coming from 21 lenders. Admission, and even a proper catalogue, were free.

Exhibition catalogue, Silver End (1935) Courtesy of Courtauld Institute Book Library

Surprisingly, in a visitor survey the Van Gogh work was only one among the eleven most popular pictures. The others, including a few now-forgotten names, were Gerald Brockhurst, William Nicholson, Walter Sickert, Muirhead Bone, Bernard Eyre Walker, Annie Swynnerton, Augustus John, David Cameron, Mark Gertler and Alfred Munnings. Works by John Constable, Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley failed to make it onto the list of favourites.

Running from 30 March to 27 April 1935, the show attracted 6,000 adult visitors—not bad for a village. Three unemployed men were paid as “watchmen”. The total cost of organising the exhibition was around £100, equivalent to just over 2 pence a head (£1.50 in today’s money).

The Silver End show was to be the first of a series of 16 “Art for the People” exhibitions that travelled to various smaller venues in England between 1935 and 1940. Courtauld went on to lend Peach Trees in Blossom to Blackburn and Newcastle in 1937.

The Art for the People scheme ultimately led to the creation of the Arts Council. Serota, a former Tate director, tells The Art Newspaper that the Silver End experiment should be regarded as “a forerunner of the wartime activities of the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts”, the success of which led to the creation of the Arts Council in 1946. Serota stresses that “the ‘national programmes’ of Tate and other national museums can be traced back to Samuel Courtauld’s enthusiasm for Van Gogh and the Post-Impressionists”.

For the Courtauld Gallery, the Silver End exhibition continues to represent an inspiration. Currently closed for building work until next spring, the gallery has for the past two years been lending major paintings to regional collections under its own National Partners scheme (now somewhat curtailed by coronavirus closures).

Van Gogh himself would be delighted that his Provençal landscape had been enjoyed by the factory workers of Silver End. When Vincent set out to make several lithographs in 1882, early in his career, he told his brother Theo that he regarded them as “prints for the people”.

In other Van Gogh news

• Tokyo’s Sompo Museum of Art has just announced the cancellation of its major exhibition Van Gogh and Still Life: from Tradition to Innovation (originally scheduled for 10 October-27 December). Despite the coronavirus crisis it was still planned to go ahead, but had to be dropped at this very late stage because of the transport difficulties of bringing pictures from Europe. Let’s hope it will be rearranged for a future year.

• Don McLean’s original handwritten lyrics for his song Vincent (Starry Starry Night) (1971), has just gone on sale with the Californian company Moments in Time. The price: $1.5m.

• And finally, a reminder on mask-wearing from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Vincent van Gogh’s Self-portrait (1889), adapted for the coronavirus era to publicise the reopening of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC