A legal battle between the French scholar Marc Restellini and the Wildenstein Plattner Institute (WPI) has once again laid bare the bitter rivalries in the lucrative field of Amedeo Modigliani attribution and the reputations at stake.

Restellini’s motive in bringing the lawsuit against the WPI is to lay claim to the Modigliani catalogue raisonné he authored and the extensive scholarship behind it. The legal complaint also exposes a seemingly problematic unnamed Modigliani painting, which it says was sold last year for nearly $5m. The Art Newspaper can reveal that this painting is Modigliani’s Portrait of Beatrice Hastings Seated (1915), which has been sold twice by Christie’s in the past 25 years, in 1997 and then again in 2019.

Restellini claims the work has been substantially modified since Modigliani completed it in 1915 and gave it to Paul Guillaume, his Paris dealer, who—as was his custom—photographed it. But no alteration was mentioned in Christie’s cataloguing in 1997 or 2019.

The painting is cited in Restellini’s case to point out the flaws of Ambrogio Ceroni’s Modigliani catalogue raisonné, first published in 1958, revised in 1965 and 1970, and now regarded by many as the most reliable authority in authenticating a notoriously forged artist—a crown that Restellini hopes to wrest from Ceroni with the publication of his own long-awaited catalogue raisonné of the artist next year.

Restellini wants the Wildenstein Plattner Institute to return his research ITAR-TASS News Agency/Alamy Stock Photo

At stake is not only the value of Restellini’s scholarship, but also the credibility of a host of Modigilianis owned by some of the world’s top collectors. Daniel Levy, Restellini’s US counsel, says his catalogue will admit around 80 Modiglianis not included in Ceroni and omit “at least 15 paintings listed in the Ceroni catalogue”, such as the Comte Wielhorski (1916, Ceroni number 151) and Beatrice Hastings Seated, which he deems not to be right. It will also, Levy says, “correct more than 50% of the dates of paintings contained in the Ceroni” based on “extensive research” and limit Modigliani’s entire production to around 350 works.

Restellini’s complaint claims the “reliance on Ceroni’s flawed catalogue raisonné has caused substantial problems in the market for Modigliani works”. Without naming Christie’s or the painting, it says that in November 1997 and again in November 2019, “a major New York auction house” sold a work that was presented as being “entirely by the hand of Modigliani”. The complaint states it sold in 1997 for $2.6m and last year for an under-estimate $4.8m (with fees).

In accepting and authenticating the work, the complaint claims, the auction house “relied substantially on the fact that this work was included in the Ceroni catalogue raisonné” and represented it as “authentic despite, among other derogatory information about the work, indications in Modigliani literature and other catalogues raisonnés, which the Auction House had consulted, that the work had been modified after Modigliani completed the work in or about 1915 and provided it to one of his Paris dealers”.

Following the 1997 sale, Restellini says he informed Christie’s that the work “was not in the same form and appearance” as it was in 1915, showing the auction house a photograph from Guillaume’s archives as evidence. Restellini did not see the painting in person at Christie’s at the time, nor did he see it in November last year.

Unfinished business

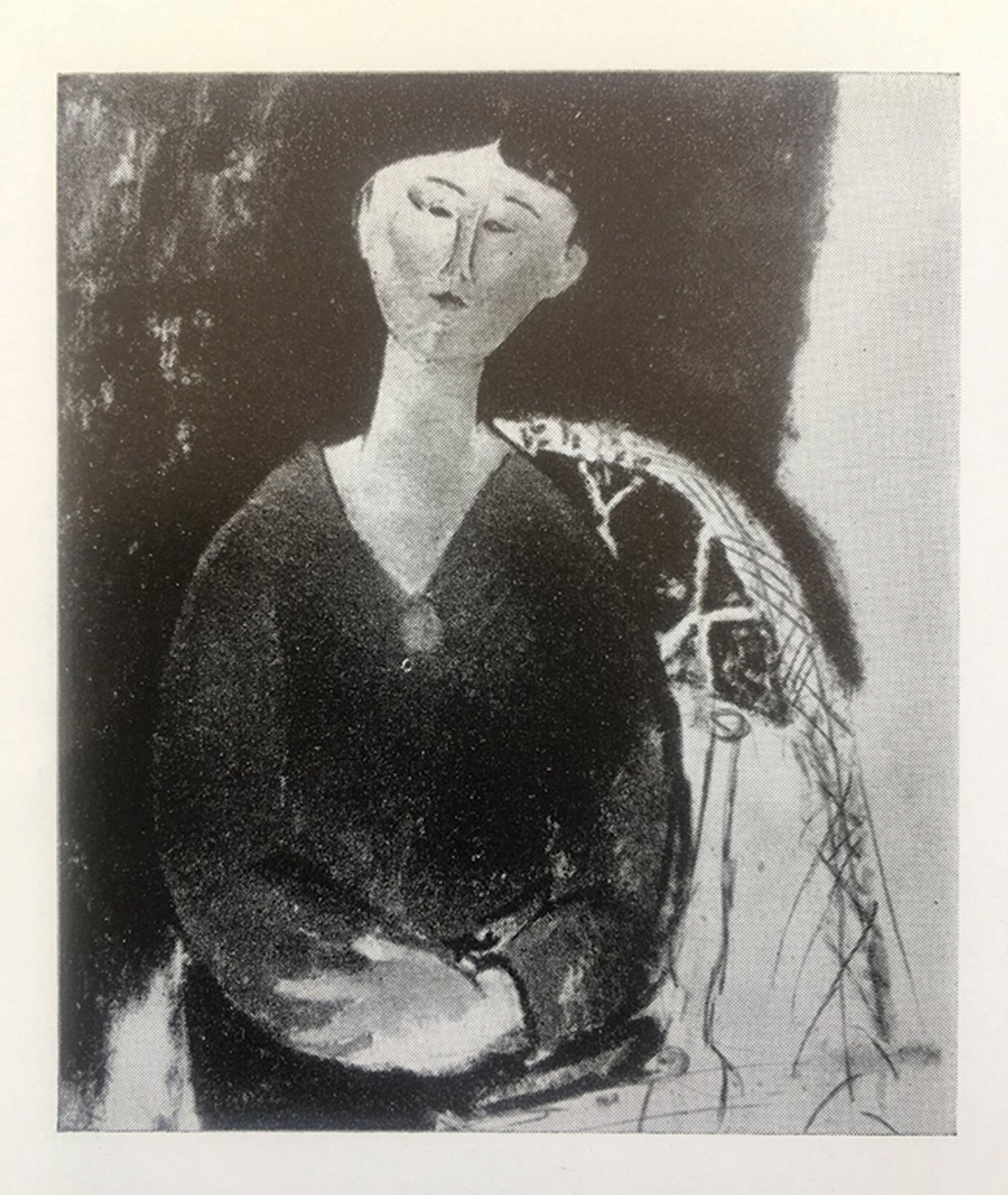

The Art Newspaper has compared two reproductions of the work published in catalogues raisonnés of 1953 and 1958, between which the portrait of Beatrice Hastings Seated was owned by a collector in Milan (where Ceroni also lived). In Gualtieri di San Lazzaro’s Modigliani catalogue raisonné of 1953, the black-and-white photograph illustrating Beatrice Hastings Seated, which has been cropped so the signature cannot be seen, appears to show areas left unfinished. In the photographs used in Ceroni’s 1958 catalogue and again in Christie’s 2019 catalogue, the background of the painting appears more finished, the table and green vase on top of it painted in, and the shadow behind the sitter’s head seemingly a different shape.

The image in San Lazzaro’s 1953 catalogue raisonné shows unfinished areas Modigliani par San Lazzaro,Editions du Chêne (1953)

Christie’s included the San Lazzaro listing in the lot literature in the 1997 and 2019 catalogues, alongside the work’s inclusion in John Lanthemann’s 1970 catalogue raisonné, in which the author writes: “This magnificent painting has undergone retouching (as shown in an old photograph).” But no mention of these modifications is made in the Christie’s description.

The portrait of Beatrice Hastings has made an appearance in the press before. In 2004, Marc Spiegler wrote in Artnews that in 1997, Restellini “declared the work a genuine Modigliani that had been badly compromised by extensive overpainting”. Restellini told Spiegler: “It had been transformed by someone else to make it more marketable. I showed Christie’s the original work’s photograph from the Paul Guillaume archives and said I could never include the painting as it stands today, because to me that is fake.” A Christie’s spokeswoman responded at the time: “While somewhat restored, the painting’s condition was not atypical of works by Modigliani, and therefore the house stands behind Ceroni’s attribution.”

When contacted by The Art Newspaper in August, Christie’s declined to comment as it is not a party to the Restellini v. WPI complaint.

Levy says: “Christie’s relied on the fact that this work was included in the Ceroni catalogue raisonné in selling the painting in 1997. Shortly after the first sale, Mr. Restellini informed Christie’s that the work was not in the same form as when Modigliani provided it to his dealer and provided an archival photo of the work as it was when Modigliani’s dealer had it.” Levy says that Restellini is “unaware whether Christie’s performed any scientific analysis of the work when Christie’s accepted the same work for sale in 2019 [Restellini has also not scientifically examined Beatrice Hastings Seated].”

Levy adds: “unlike Ceroni, Mr. Restellini’s opinion about what works should, and should not, be included in his catalogue is supported by extensive scientific analysis of many works plus other in-depth research, including first-hand archival material previously unavailable.”

One dealer who trades in Modigliani works and is familiar with the painting’s history, but asks to remain anonymous, says: “Clearly significant retouching occurred in the 1950s, which should have been referenced.” While Ceroni’s 1970 catalogue raisonné is, they say, “usually still the benchmark for the industry”, Restellini is “a leading Modigliani expert working today, so his opinion should be factored in”.

Modigliani monopoly?

Restellini’s lawsuit against the WPI hinges on his claim that the institute allegedly plans to publish his Modigliani catalogue raisonné online before Restellini has published it himself next year. He claims the WPI is holding his work—including all the “trade secrets” of his valuable scientific research—“hostage”, violating his copyright and trying to pass off Restellini’s work as its own without compensation or attribution. Restellini is demanding that the institute be stopped from publishing and disseminating his research, and be forced to destroy all digital copies.

On 14 August, the WPI filed a counter-complaint, in which it not only maintains it has the right to publish Restellini’s work but also says the scholar and his Institut Restellini are infringing its copyright material, therefore it is entitled to a share of their profits—the WPI claims Restellini’s institute charges around €30,000 per Modigliani inquiry. Levy declines to comment specifically on this figure, but says: “Institut Restellini’s prices for services, from studio and specialised photographs all the way up to a complete expert and scientific analysis, are well in line with the market.”

But Restellini, the WPI claims, “hopes to create monopoly power for himself over historical information about Modigliani, which Restellini further plans to leverage for his own, maximum profit”.