Nearly every art history student has heard of Aby Warburg’s unfinished final project, the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, created in the years preceding the German art historian’s death in 1929. But few have more than a cursory idea of its contents. Now, after “50 years of denial”—as the curators Roberto Ohrt and Axel Heil refer to the period since the art historian Ernst Gombrich categorised the work as a failure—it is to be exhibited at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. Unlike previous attempts to show the entire 63 panels (each measuring 2m by 1.5m), the HKW show will include not only reproductions but around 80% of the actual images used for the atlas’s last version, recovered through extensive research in the photographic collection of the Warburg Institute in London.

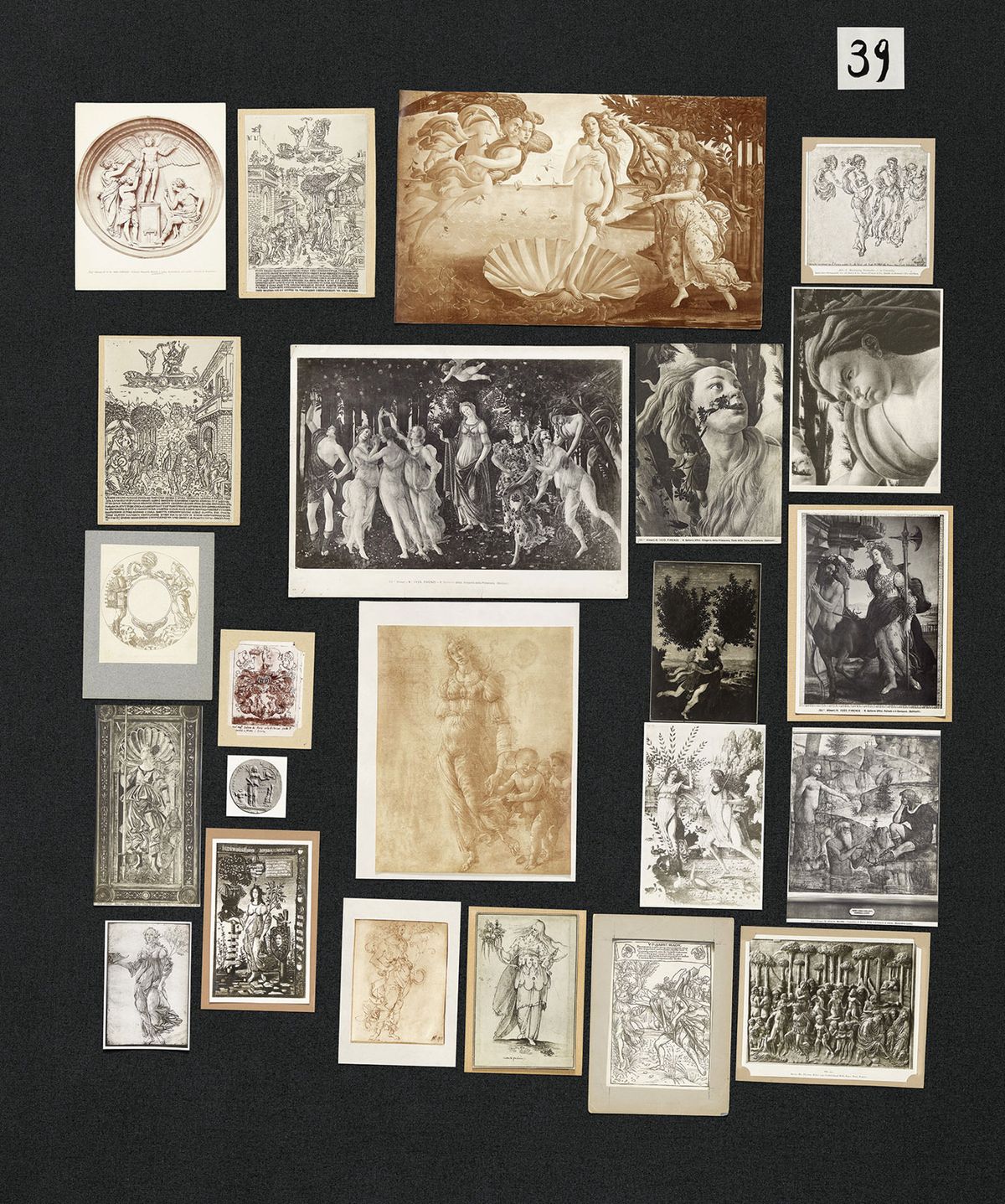

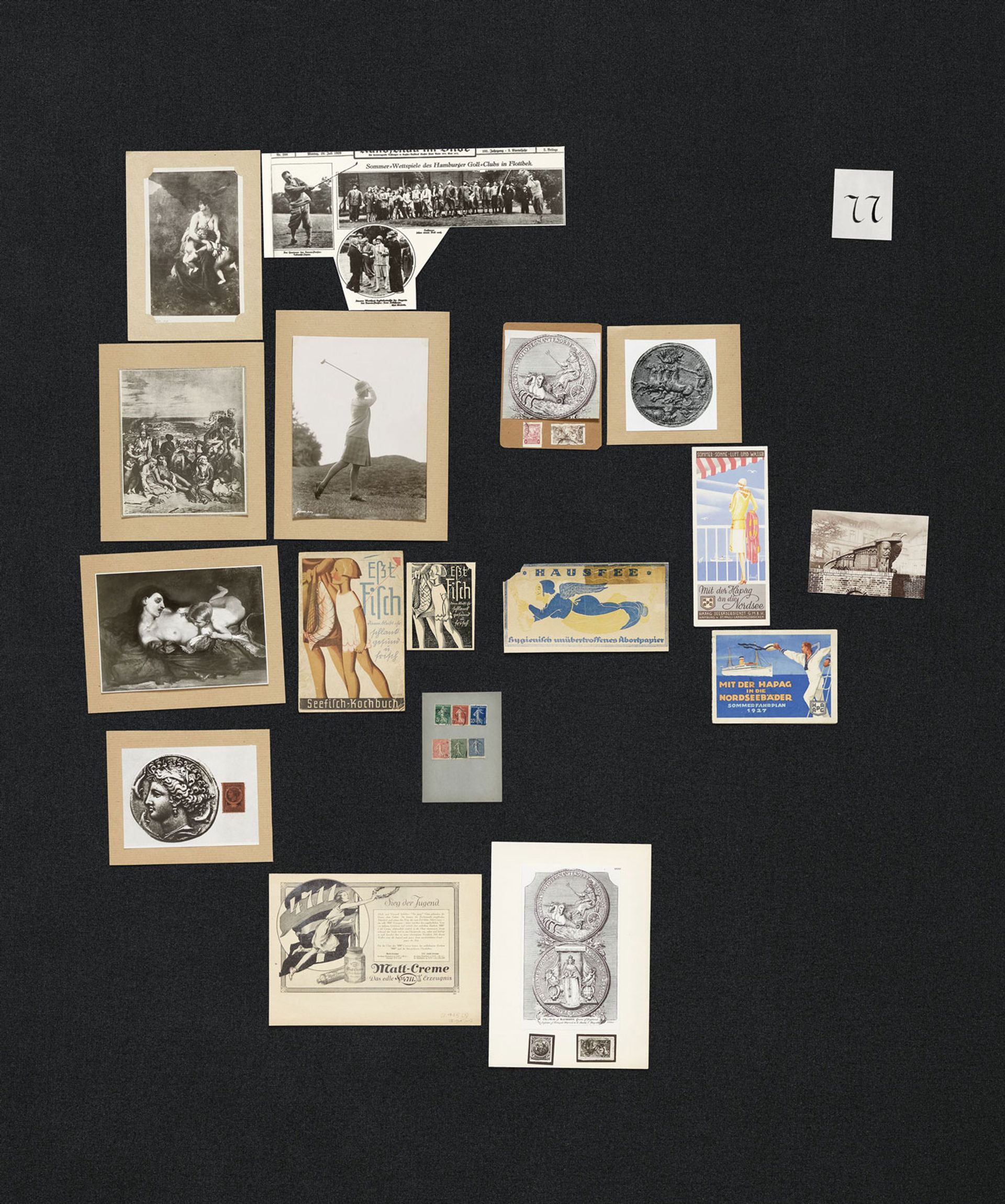

Mnemosyne is an atlas of pictures, carefully juxtaposed and sequenced to provide insights into the nature of thinking through art. Warburg’s ambition was to make visible recurrences of symbols and gestures, themes and styles, from antiquity to the present day, mapping out a cartography of what the art historian considered the life and wanderings of images. The atlas is composed mostly of photographic reproductions but also graphics and prints, as well as a few drawings and watercolours. The 971 images contained in the autumn 1929 version are best known through books, such as the almost exclusively black-and-white editions compiled by Martin Warnke with Claudia Brink, and Christopher Johnson.

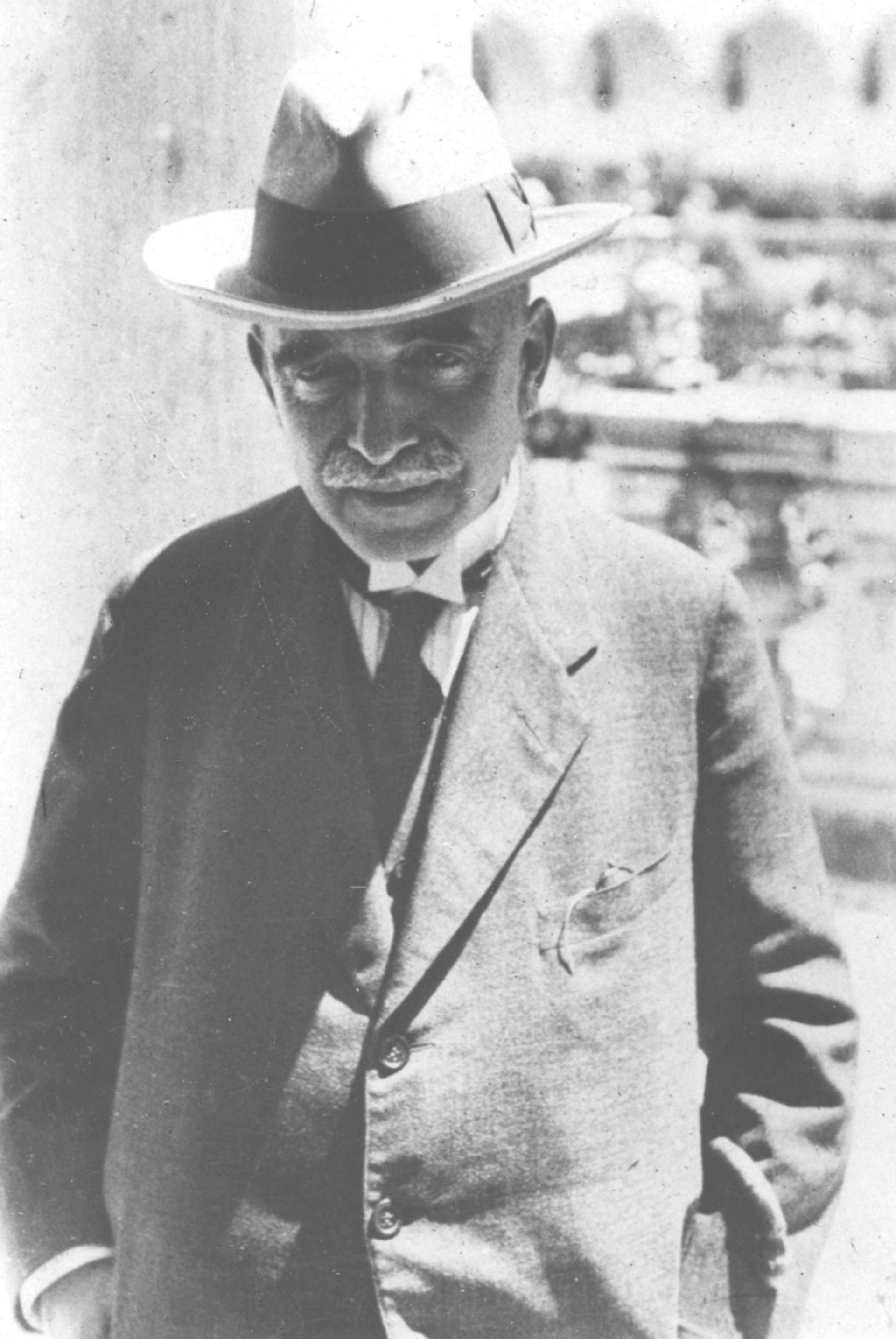

Aby Warburg photographed in Naples in May 1929 Photo: The Warburg Institute

Much attention has been devoted to tracing the pathways of meaning that Warburg intended to establish within and between panels. His plan had been to publish the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne not only as a volume of images but supplemented by texts with historical and critical commentary. The surviving captions and drafts have become a vital source of interpretation. Research for the show, beginning in 2012, uncovered more mistakes than expected in previous analysis; according to the curators, there was a need to start from scratch and re-establish the ability to read its language. A 700-page volume with extended annotations is in the works.

The major promise of the exhibition is to reconstitute the atlas as a spatial function. Mnemosyne was intended to work as a dynamic thought-space, and Warburg famously made use of the panels to illustrate lectures and presentations. To be able to walk through the reconstructed atlas and experience its non-linear, polyphonic and multi-dimensional aspects is, indeed, the whole point of the exercise.

Warburg's Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, panel 77 Photo: Wootton/fluid; Courtesy The Warburg Institute, London

Over the 90 years the images were dispersed in the Warburg Institute’s collection, many ended up remounted, cut or otherwise modified. Those 1,000-odd images, filed away in forgetfulness, will now be reunited as a tribute to the persistence of memory—which, after all, is the meaning of mnemosyne.

• Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 4 September-30 November