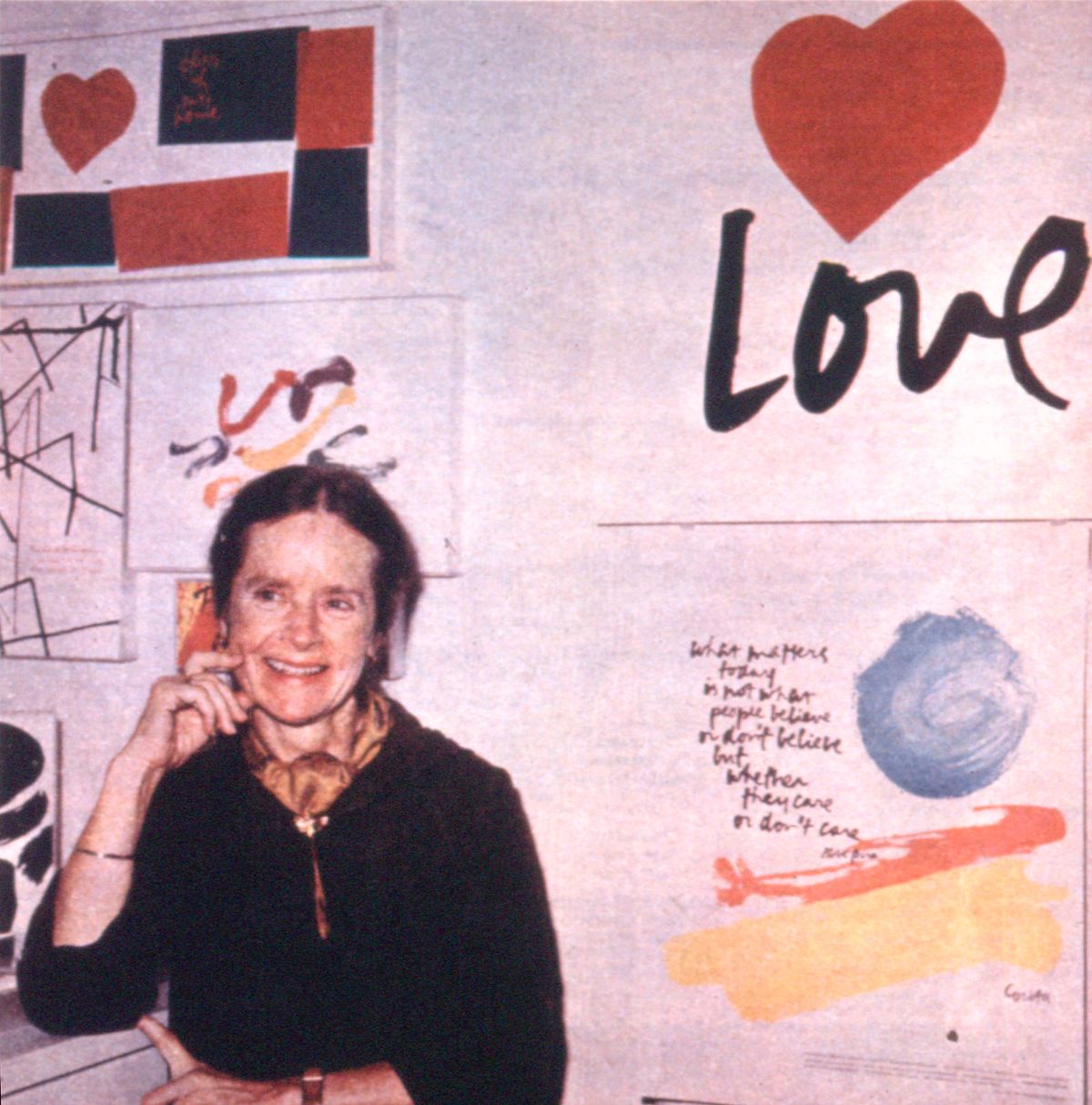

Known as the “nun-turned-artist” and remembered for her colourful serigraphs that retaliated against social injustice with the boundless power of love, the late artist Corita Kent was a luminary of the Los Angeles art scene in the 1960s and is often described as a harbinger of Andy Warhol. Now more than three decades after her death in 1986, a campaign is underway to save her former studio from demolition and to designate the space as a historic-cultural monument.

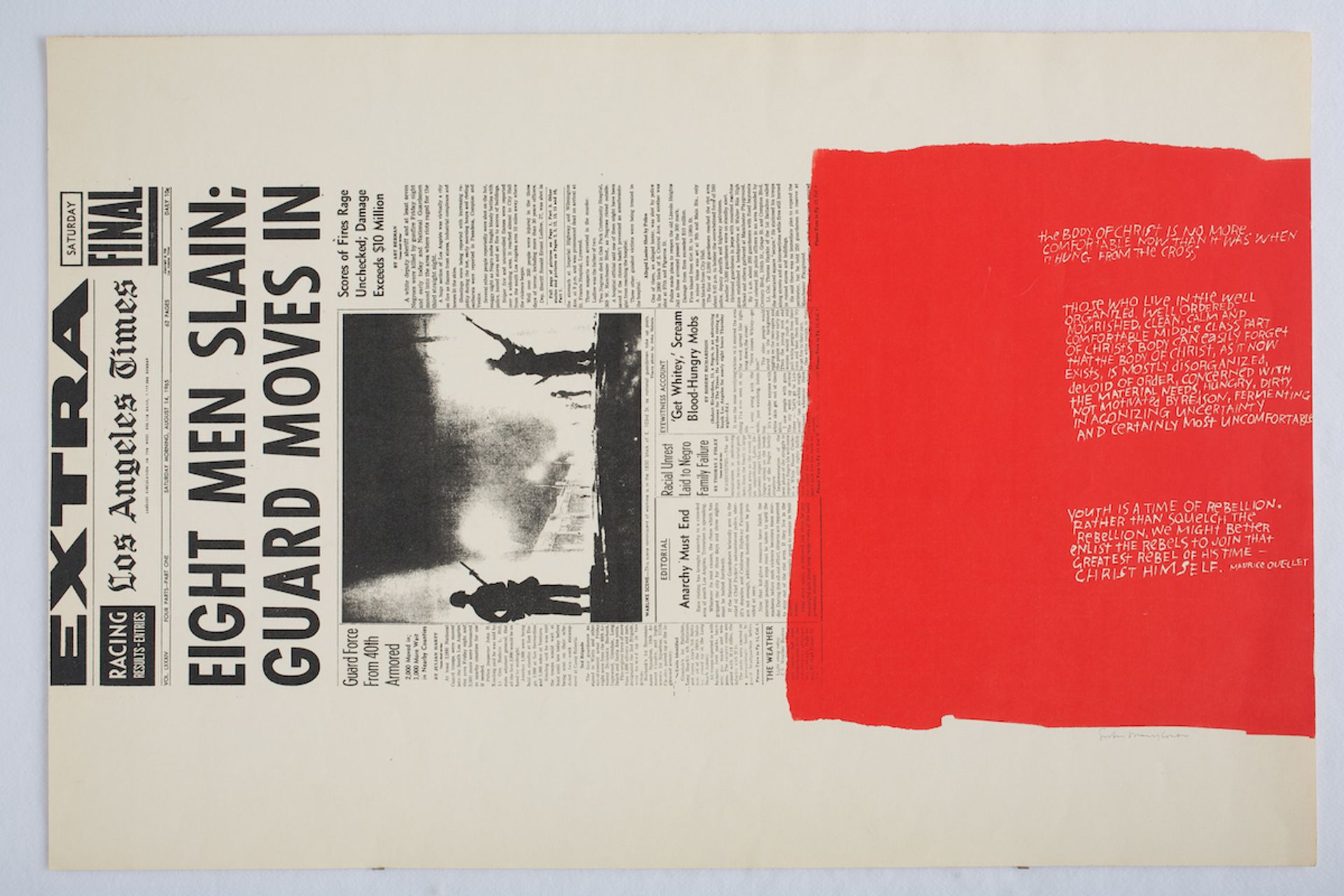

The building at 5518 Franklin Avenue is currently a dry cleaner that is scheduled to be demolished to create space for a parking lot. The site served as Kent’s studio between 1960-68, when she produced some of her most notable pieces like My People (1965), which addressed the Watts riots in Los Angeles in 1965—a six-day period of civil unrest resulting in 34 deaths that followed the police beating of the African-American man Marquette Frye.

“Her work always came from themes of love, justice and hope,” says Nellie Scott, the director of the Corita Art Center, which was established after Kent’s death and sits across the street from her former studio. “There’s been a resurgence of interest in her work now when people are increasingly looking to past inspirational leaders during tough times.”

Corita Kent, My People, 1965 The Corita Kent Art Center

Kent was born Frances Elizabeth Kent in Fort Dodge, Iowa, in 1918, but spent most of her life in Los Angeles. She joined the order of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, a progressive Roman Catholic congregation, in 1936 at age 18. With her sisters, Kent began experimenting with silk-screening as a vehicle for political demonstrations related to the Civil Rights Movement and the first-wave feminist movement.

During her time at the Immaculate Heart College, Kent also enrolled in classes at the Otis College of Art and Design and the Chouinard Art Institute, and earned her bachelor degree in art history from the University of Southern California in 1951. Her work during this time was “inspired by what was happening not only in the country but locally in Los Angeles; she pulled from the streets to touch on subjects like poverty, hunger and adversity”, Scott says.

In 1968—after a series of conflicts with a conservative cardinal who called for nuns to rein-in their political demonstrations, and who called her work “weird and sinister”—Kent left the church to pursue a full-time career as an artist and arts educator. Although she relocated to Boston the same year, her “roots as an educator, artist and social justice activist were very much centralised in Los Angeles, and she produced her most important work here”, Scott says.

In 2018, the city of Los Angeles declared 20 November, Kent’s birthday, to be Corita Kent Day in honour of her contributions to the city (the city of Boston gave the artist the same honour in 2015). “Especially because of this recent recognition, it’s important to highlight that once her studio—this critical part of history—is demolished, we can’t go backwards,” Scott says.

The Corita Art Center was established when the Immaculate Heart of Mary was given stewardship of Kent’s estate and archive, which spans more than 30,000 pieces. Organisers hope that their proposal to stop the demolition of her studio will “help preserve this valuable space that is not just a landmark but could be a cultural and economic driver for the community”, Scott says.

Corita Kent's studio in the 1960s The Corita Kent Art Center

The campaign is still in the early stages but organisers hope to be involved in a zoning board meeting in the coming weeks, and have received “incredible support from the community”, Scott says, including many letters of support from Kent’s past students and contemporaries. Organisers are specifically petitioning to the Los Angeles City Council member Mitch O’Farrell, who represents the 13th district, where the former studio is located, and have launched a website urging the public to join their effort.

“When you have a notable artist who shared so much of themselves with the world, there’s a ripple effect to that energy,” Scott says. “Love, hope, justice—what a beautiful thing to be a part of.”