The Grand Egyptian Museum will finally be finished by the end of this year. So promises Major General Atef Moftah, who in 2016 was personally appointed by President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi to lead one of the most prestigious—and delayed—museum building projects of the 21st century. The museum was originally scheduled to open in 2011.

In a behind-the-scenes tour of the construction site on the Giza plateau, Moftah estimates that the building is now “96.5%” complete. Then it will take “four to six months” in 2021 to install some 100,000 artefacts, including 3,000 treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The museum was originally intended to open in 2011 Courtesy CNNI

In April, the president pushed back the opening date of the museum from late 2020 to 2021. Moftah will not be drawn on the new timetable because of “Covid 19-developments”. World leaders will also need reasonable notice to attend, for as the general puts it, “Egypt’s gift to the world deserves a huge celebration”.

A trained engineer, Moftah is proud of his own contribution to the building: the main façade, a long freestanding wall. “This is my personal design,” he says. “I saved more than $180m from the budget. The previous design was very complicated and would’ve taken a lot of time.”

The Dublin-based architects Heneghan Peng, who won the competition to design the museum back in 2003, had planned a 1km-long wall using translucent onyx to be back-lit at night. Their triangular wall motif—chosen for stability rather than in homage to the neighbouring ancient Pyramids—remains the same. But Moftah’s modified wall has been achieved in glass and appears to be about half the length.

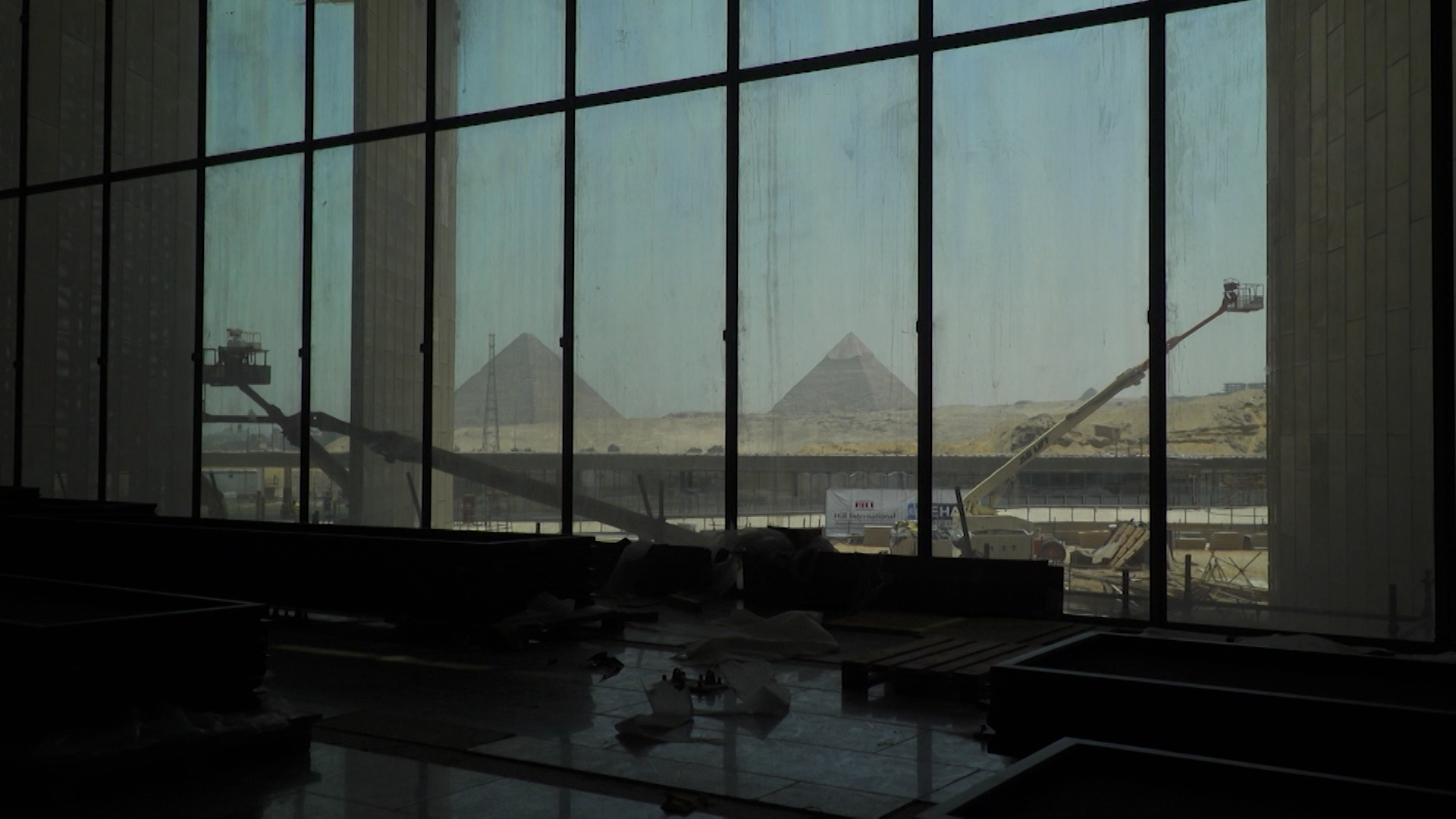

The museum has a panoramic view of the pyramids of Giza Courtesy CNNI

The Grand Egyptian Museum is unquestionably grand. At 490,000 sq. m, it is the size of a major airport terminal. Egypt’s minister of antiquities and tourism, Khaled al-Anany, calls it the “Fourth Pyramid”, and naturally, it comes with a panoramic view of the ancient monuments.

Even with distractions—construction noise, scaffolding and men in blue boiler suits liberally spraying disinfectant—the atrium is breathtaking. “You could park a 747” inside, says architect Roisin Heneghan, who describes the museum’s exhibition space as “the size of four football fields”.

The museum's atrium is dominated by a statue of Ramses the Great Courtesy CNNI

The largest artefact—an 11m-high, 83-ton red granite statue of Ramses the Great—arrived early, in January 2018, so the atrium could be built around it. On the grand staircase behind Ramses stand 87 statues of pharaohs and Egyptian gods, most still under protective wraps. Once unveiled, they will offer tourists a potted history of Ancient Egypt as they ascend.

The Tutankhamun galleries upstairs, the museum’s star attraction, are still out of bounds. The Egyptians have indicated that they will show examples of everything from the 3,300-year-old Tutankhamun collection for the first time. Howard Carter counted 5,398 artefacts when he discovered the tomb in 1922; the museum database puts the figure at 5,600. Besides the gold treasures—death mask, diadem, coffins, chariots, jewellery—visitors can expect to see more everyday objects: the pharaoh’s walking sticks, loincloths, boomerangs, games and food boxes of coriander seeds and juniper berries.

Carter was surprised by how small the tomb was—just four rooms spanning 110 sq. m. The museum will have a replica tomb, the same that opened in the Valley of the Kings in 2014. But the galleries will be more than 60 times the size of the original tomb, 7,000 sq. m in total. The intention is to display the treasures in four spaces and in the room order that Carter found them.

The University of Oxford’s Griffith Institute, which holds the Carter archive, is supplying digital scans of around 100 historic photographs of the excavation by Harry Burton. These will include the portrait of the Egyptian waterboy said to have found the first step down to the tomb, pictured wearing a scarab pendant of Tutankhamun. The photograph and pendant feature together in the current Tutankhamun touring exhibition, seen by 2.7 million visitors so far in Los Angeles, Paris and London. The funds raised from the show—more than $20m to date—are expected to support the new museum.

The Tutankhamun galleries upstairs, the museum’s star attraction, are still out of bounds Courtesy CNNI

Egypt’s best-known Egyptologist, Zahi Hawass, ebulliently claims the Grand Egyptian Museum will be “the largest museum in the world” (some Chinese museums would contest the title). In an interview at the old Egyptian Museum in central Cairo, he explains which exhibits will replace the Tutankhamun death mask and other top tourist attractions when they move to Giza. The plan is to bring in “20 royal mummies” and the treasures of Tanis, gold funerary artefacts recovered from royal tombs in the Nile Delta by the French Egyptologist Pierre Montet during the Second World War.

Many key Tutankhamun objects have already passed to the Grand Egyptian Museum’s conservation centre, which began operating in 2010. “What we are doing here is re-discovering the collections of the King,” says the museum’s head of archaeology Tayeb Abbas. “This work is just as important as Carter’s.”

Tutankhamun’s 2.2m-long outer coffin of gilded cypress wood was transferred to the centre last year—the first time it had left the tomb in the Valley of the Kings near Luxor, 300 miles away. Despite local resistance, the coffin will not return. Conserving this single artefact, including fumigation, has taken around eight months. It will be part of the new display along with Tutankhamun’s two inner coffins.

The Grand Egyptian Museum also coveted the pharaoh’s mummy. It was due to be moved from the tomb in May but the locals managed to win the argument. They regard the mummy as their ancestor and a tourist attraction in his own right. Hawass is sympathetic, saying that: “The people of Luxor think that their grandfather should stay there, and I really do respect this. The mummy will stay there.”

An Egyptian conservator at work Courtesy CNNI

Japan is a major backer of the museum, contributing loans worth around 75% of the reported $1bn cost and expertise through the Japan International Cooperation Agency, which has trained hundreds of Egyptian conservators. At the conservation centre, an Egyptian-Japanese team has been carrying out the first scientific study of textiles from Tutankhamun’s tomb. Evidently of little interest to Carter, textiles were among the most deteriorated artefacts found in the tomb.

There are 115 loincloths made of the finest linen and 93 pairs of shoes, mostly sandals. The conservators have identified pharaonic headgear, socks and an archer’s arm pad. Japanese textile expert Mie Ishii says that the clothes tell you a lot about the wearer. In her view, Tutankhamun was “a very sensitive young man, fine-boned, always clean and spotless” and dressed in “the most beautiful and comfortable cloths that the kingdom could offer”.

The conservation centre at the Grand Egyptian Museum has made a number of intriguing discoveries about the Tutankhamun collection Courtesy CNNI

The laboratories have made a number of other intriguing discoveries in recent years. The hardwood used for Tutankhamun’s ceremonial and hunting chariots was elm, originating in the eastern Mediterranean, 500 miles from ancient Thebes (modern Luxor). A puzzling series of gold-leaf rods has been identified as components of a sunshade for a ceremonial chariot, the oldest sunshade ever found. And analysis has determined that the iron blade of a dagger found with Tutankhamun’s mummy almost certainly came from a meteorite.

Hawass is also reviving his intermittent investigation into how Tutankhamun died. He says DNA analysis conducted with “a very sophisticated machine from a San Diego company” will determine whether Tutankhamun had an infection on his leg. “If he had an infection, that means that he died in an accident,” Hawass says, a conclusion that would disprove the enduring theory that he was murdered. The irrepressible Egyptologist has also written a Tutankhamun opera that he hopes will be performed at the opening of the new museum.

The Grand Egyptian Museum is obviously of huge national significance. General Moftah says that President Sisi “wants perfection” in the building; they meet at least once a month, sometimes weekly. Egypt’s economy badly needs tourists to come back and Moftah anticipates 2 to 3 million visitors to the new museum in the first year. The longer-term hope is for up to 8 million a year, and the museum certainly has the capacity.

It is estimated that it took Pharaoh Khufu around 20 years to build himself a tomb, the Great Pyramid. From the announcement of the architectural competition in 2002 to the planned opening next year, the Grand Egyptian Museum will also have taken almost 20 years. If by any chance the opening is postponed yet again, there is always the possibility of opening in 2022—conveniently the centenary of Howard Carter’s discovery.

- Nicholas Glass’s documentary on the Grand Egyptian Museum is available to view on