“It's interesting how history can intervene in what you're doing,” says the sculptor Melvin Edwards. For the last two years, he has been working with the Public Art Fund on the first thematic survey of his public sculpture titled Brighter Days, which was originally scheduled to open in New York’s City Hall Park in June. Delayed a month due to the coronavirus, the show has now been postponed until spring 2021, in light of the protests outside City Hall in the park itself and across the city, incited by the brutal killing of George Floyd by the hands of police.

“As demonstrations outside City Hall Park were transitioning into an occupation, we felt strongly that it was vital to keep the focus on the protest,” says Nicholas Baume, the Public Art Fund's director and chief curator who made the decision together with Edwards to push back the show. “It is essential that the Black Lives Matter movement and calls for justice remain front and center,” continues Baume, who has closely monitored the situation. On 22 July, police cleared an encampment of protestors from the park, but marches and demonstrations continued this Tuesday, with police making several arrests according to posts on social media.

With such a momentous social movement setting the stage, when the exhibition is ultimately installed, “it’s possible people will pay more attention given the awareness of other things,” Edwards says.

Since beginning his best-known and ongoing series Lynch Fragments in 1963, which responds to racial violence in the US, the 83-year-old African American artist has worked experimentally, welding metal into abstract geometric forms with allusive figurative elements. Brighter Days will include six large-scale pieces dating from 1970 to the present that poetically explore the motifs of the chain and the rocker in formal, cultural and personal ways.

“Mel talks about the chain as being this literal motif that is about oppression and restraint but also about linkages of inter-connectivity—between generations, between communities, between individuals,” says Daniel Palmer, the Public Art Fund curator who organised the show. He proposed installing the exhibition on the green space outside City Hall, both because of its prestige as the seat of New York’s government, and its history as an African burial ground in the colonial era and the commons where the Declaration of Independence was first read aloud to an audience.

“Thinking about the motif of the rocker as this historical back and forth,” Palmer says, “this site just felt like it worked on so many levels and is even more meaningful right now with everything going on in the city.”

Raised in Houston under segregation—the city where Floyd also grew up—“his life easily could be mine,” Edwards reflects. “I saw the picture him, which had him in the football jersey of my rival high school. He was very familiar.” Edwards played football at the University of Southern California but chose to pursue art there under the mentorship of the Hungarian painter Francis de Erdely. Edwards's experience as an athlete has always informed his sculpture and consideration of balance, motion and poise.

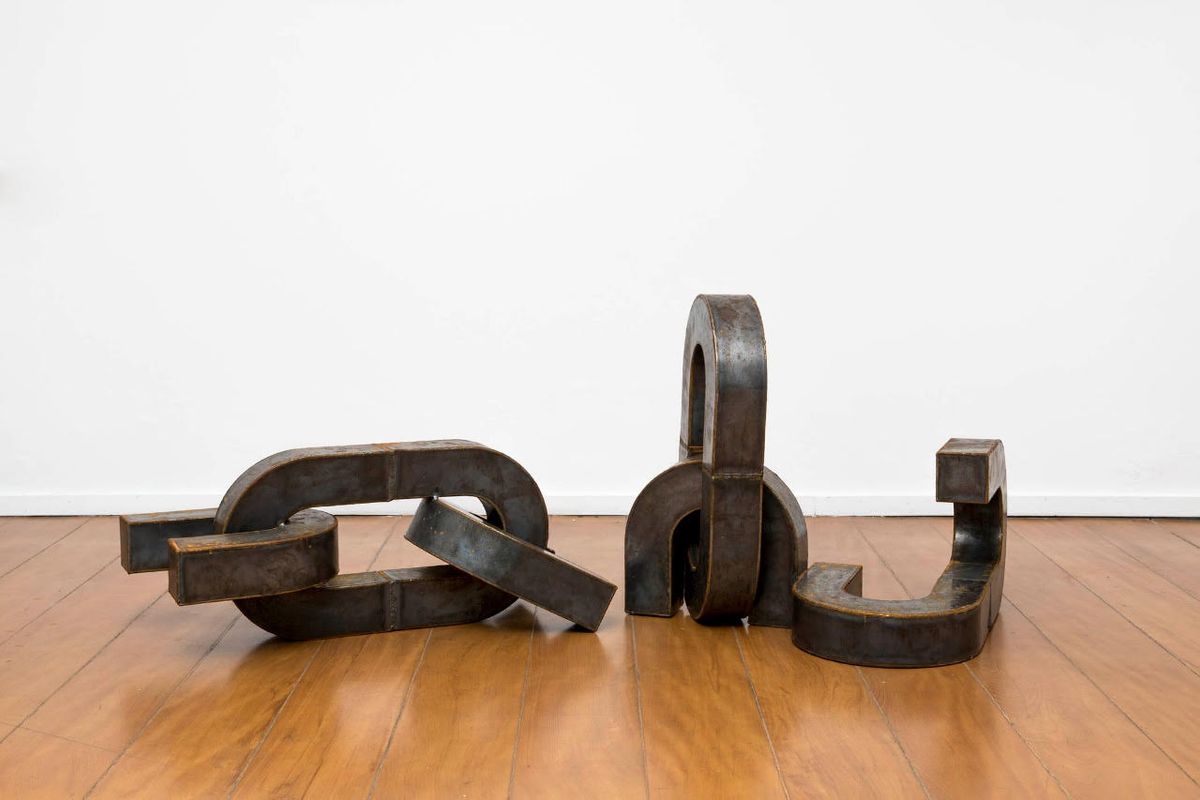

Melvin Edwards , Homage to Coco (1970 ) Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London © Melvin Edwards/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This is evident in the earliest piece in the show, Homage to Coco, named after the artist's grandmother. An investigation of kinetic dynamics, the symmetrical painted-steel red rocker is composed of two semi-circles attached at their top ends with two long metal strips, from which chains are strung in arcs that sway when weight is applied to either side.

“The balance and the motion as a response to action is so essential to Mel's approach to welding and sculpting,” says Palmer, of the 1970 piece he calls a major breakthrough for the artist, who has lived and worked in New York since 1967. “Coming out of a moment in geometric abstraction and post-minimalist sculpture, it's the beginning of him being able to really make it his own, using the language of his own experience and the historical dimension of the African diaspora related to his grandmother.” Another sculpture, Ukpo, Edo (1993/96), refers to a village in Nigeria and underscores Edwards's deep personal connection to Africa, where he often returns to work in Senegal.

Song of the Broken Chains, a new commission in stainless steel rising eight feet high and completed for the exhibition, dismantles the anatomy of a chain. This includes a perfect figure 8 between two oversized links and other configurations where linkages are taken apart.

Melvin Edwards Photo: Ross Collab. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York

Chains, created by metalworkers as a stronger alternative to fiber ropes, “were large enough to hold ships and sometimes small enough to put a little pearl necklace around someone's neck,” Edwards says. “Human beings are chained to their existence psychologically, economically, physiologically—all kinds of ways. The breaking of chains produces many other possibilities.”

“We couldn't have realised just how resonant this piece would be to this moment,” Palmer says. He hopes the exhibition will encourage viewers to seek out the four other public sculptures by Edwards permanently sited around the city—two in Harlem and one each in Queens and Brooklyn.

“I'm always working toward the idea that we improve the human predicament,” Edwards says. “If there are going to be brighter days,” he continues, in a nod to the exhibition title, “we have to do it. We can create a better world or not. It's a large topic. I've got a lot more sculpture to make.”

• This article was updated after Public Art Fund announced a further postponement of the show, from October 2020 to April/May 2021