Gayle Greenhill was an adventurous woman, a trait that can be clearly seen in the photography collection she built with her husband, the financier Robert Greenhill, who has now donated more than 300 works in her memory to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) New York. The “transformative gift”, as the museum describes it, includes examples by artists who pushed the artistic boundaries of the medium, such as Edward Steichen, Diane Arbus, Karl Blossfeldt, William Eggleston, Jan Groover, André Kertész, László Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, and Cindy Sherman. As well as establishing the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MoMA, the gift will allow for the creation of an endowment fund for future exhibitions and acquisitions through the potential sale of some works.

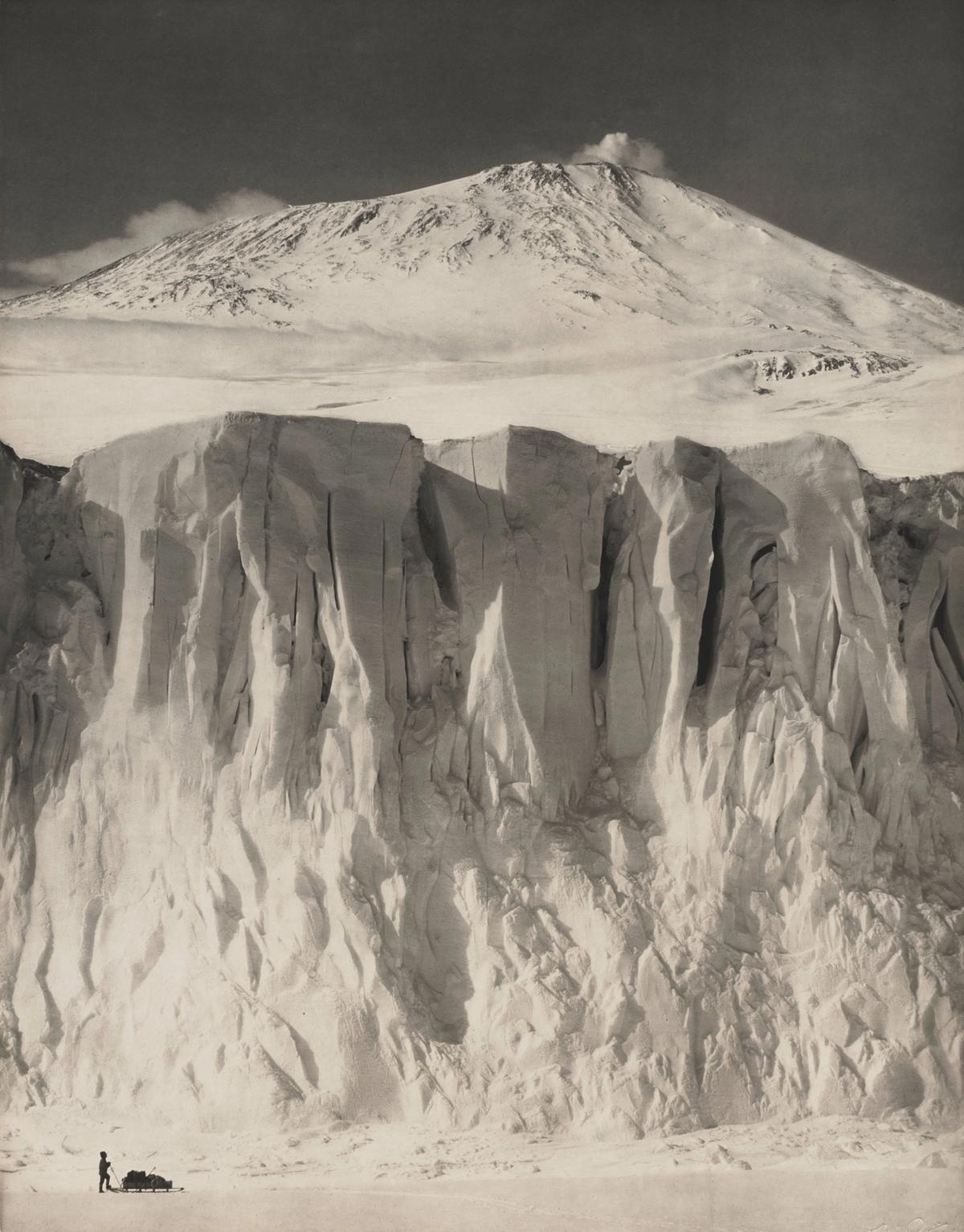

“It's an amazing collection, from start to finish. It has all of the hallmarks, meaning extraordinary singular works of art chosen with incredible discretion and passion,” says Sarah Meister, MoMA’s photography curator, “and then also a very personal take on, for instance, exploration and aviation, which really characterise their collection and distinguish it.” This theme of exploration can be seen literally, in the case of Herbert Ponting’s documentary photographs of Robert F. Scott’s doomed Antarctic expedition in 1910, and through the creative experimentation of artists such as Moholy-Nagy and Jan Groover.

Jan Groover, Untitled (around 1979) The Gayle Greenhill Collection. Gift of Robert F. Greenhill © 2020 Estate of Jan Groover

A sense of adventure is something Robert Greenhill shared with his wife, who died in 2017, aged 81. “One of the things that Gayle I did early on is get dropped in from an airplane at the Arctic Circle. We spent a month travelling north by canoe through the Arctic Ocean,” Robert says, adding that the couple made the outing on their own, without guides. “It wasn’t crowded.” The pair were even the subjects of a DuPont advertisement touting Kevlar-skinned canoes, and later took their children on similar trips to the far north. And the Greenhills’ pictures related to the development of aircraft, from the Wright Brothers’ first attempts at flight to Nasa launches, stem from Robert’s background as a pilot who has clocked 15,000 hours in command. “I flown airplanes for about 20 years, and I've flown all over the world,” he says. Gayle often joined him, getting her own pilot’s license at age 50.

Gayle brought this same spirit of discovery to her photography collection and the acquisitions she helped fund at MoMA, where she was a member of the committee on photography from 1989 to 2013. “She had an incredible eye for quality,” Meister says. Robert Greenhill echoes this, giving Gayle the chief credit for building their collection. “She'd just look at a series of photographs and she'd make a decision right away, which one or two was worth acquiring,” he says.

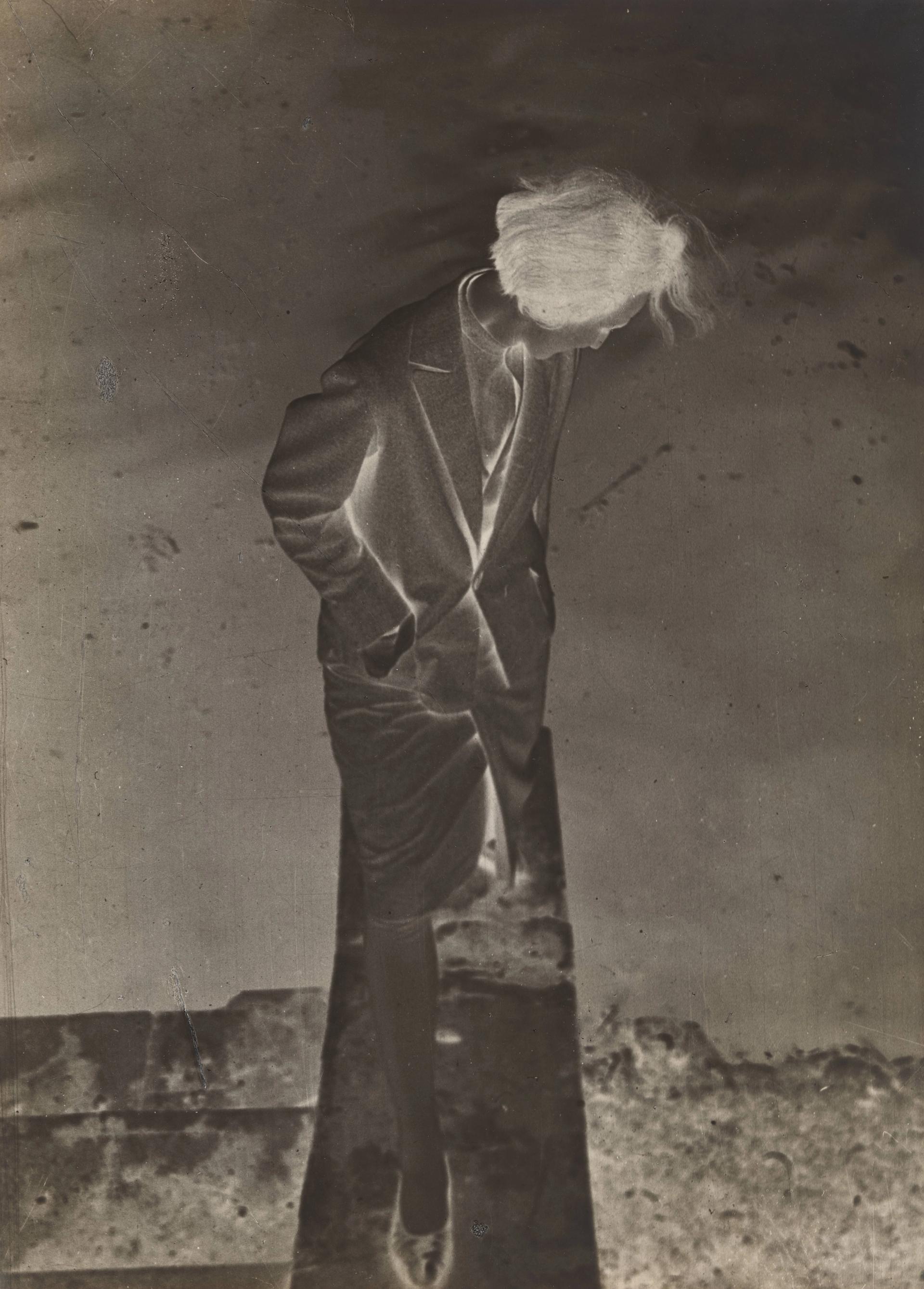

László Moholy-Nagy, Negative (Portrait) (1931) The Gayle Greenhill Collection. Gift of Robert F. Greenhill © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

“She claimed that she learned about photography through John Szarkowski [MoMA’s director of photographer from 1962 to 1991], but I think she was being modest,” Meister adds. “She had a confidence in her judgment that allowed her to understand that she wanted to bring together not necessarily similar things, but things by a wide range of makers, with a wide range of motivations.” This breadth of material will be studied over the next few years and result in an exhibition and publication of the Greenhill Collection. It could also mean that some duplicates could be found with existing works in MoMA’s collection, but the Greenhill gift allows MoMA free reign to sell some of the works to create an endowment fund that will support future exhibitions and acquisitions. “The generosity is so wide and so deep,” Meister says of this decision, adding that she can imagine selections “happening in both directions”, so if MoMA prefers the Greenhills’ print, they could deaccession a piece from the museum’s collection instead.

Characteristically, Robert Greenhill puts it in more forward-thinking terms. “This is an incredible collection, but it’s also about a period of time,” he says, adding that he would like to see the holdings continue to grow. “I think future students of photography and art are going to be pleased with the collection, they’re very lucky.”