Christo was laughing quietly to himself, relishing the memory. He’d been invited in January 2017—as exhibiting artists are—to create something in the space outside the Centre Pompidou in Paris. “We would like something new here,” said the Pompidou’s director, Bernard Blistène. Christo, sat in his New York studio, re-enacted his response. He shook his head, wagged an admonishing finger. “I will not do anything in Paris,” he told Blistène, “except wrap the Arc de Triomphe”.

How did the Pompidou team react? “I was looking at them,” he told me. “They were looking at me. And I was thinking that they’ll never do it. But we get [sic] permission in a little over a year. I was flabbergasted”. He liked the word “flabbergasted”, using it several times during our interview.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude at The Gates in 2005 Photo: Wolfgang Volz

Christo was a visionary artist with big ideas and huge ambitions. His wife and collaborator, Jeanne-Claude, died in 2009, but in half a century together they redefined what was possible in public art. They were master wrappers, covering buildings and landscapes with moving, rippling coloured fabrics. They were dreamers who got to realise many of their dreams. Doing so required extraordinary tenacity and more than a little charm.

I am an artist who is totally irrational, totally irresponsible and completely free. Nobody needs my projects. The world can live without these projects. But I need them and my friends [do]Christo

Their unquestionable masterpiece was wrapping the Reichstag in Berlin. They first imagined the project in 1971, were refused permission three times before finally realising it in 1995 after approval from the German Parliament. I remember covering the story at the time. Christo and Jeanne-Claude swept through the mêlée of journalists on top of the building, as unstoppable and inseparable as Batman and Robin. They were fun, unpretentious and crowd- and journalist-pleasers.

It was hard not to marvel at the achievement. The scale, beauty, symbolism, madness of it all—imagined and engineered by a refugee from communism. The New York Times architecture critic wrote: “It billows in the wind, it glows in the sun, it is tailored as primly as a dress and engineered as heavily as a battleship.” And to top it all, there were the couple themselves—Christo’s beaming smile and Jeanne-Claude’s fiery red hair. An estimated five million people were drawn to see the wrapped Reichstag. The piece was up for 14 days and then it was gone.

The projects were always ephemeral, never lasting more than a few weeks. They were invariably described as monumental but were more than that; they seared on the memory. And what was almost as extraordinary is that somehow the couple financed each project themselves, by selling Christo’s preparatory artwork for millions of dollars. Wrapping the Arc de Triomphe won’t leave much change out of €15m.

Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin (1971-95) Photo: Wolfgang Volz

Narrative arc

I interviewed Christo down a blurry video link to New York on 11 May, just 20 days before he died. He was his familiar good-humoured self—glasses, aureole of thinning white hair, expressive hands—telling his story and Jeanne-Claude’s in heavily accented English (“my English is very, very terrible”) and a smattering of French phrases.

He seemed freshly energised by the Arc de Triomphe project. For the last year or so, he had been working exclusively on Arc artwork: drawings, collages, photomontages. Most of the day was spent in the studio—“completely losing his sense of time because he was enjoying it”, as one of his team put it. Everything was done, he said proudly “with my own hands. I have no [studio] assistants”. He hadn’t left the house since lockdown—“the prisoner of Howard Street”, he called himself jokingly.

Christo reflected on “the incredible journey of our life”, constantly referring to “we” and “us” as if Jeanne-Claude had just stepped out of the room. Life was measured out in projects—23 realised, 47 refused—according to Christo. There was “the time of Iron Curtain in ’72, the time of Running Fence ’76, the time of Pont Neuf ’85”. He reeled off the titles and the dates.

Christo Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon were famously born on the same day, 13 June 1935—he in Bulgaria, she to a French military family in Morocco. Christo’s father was half Bulgarian, half Czech, his mother Macedonian. He went to art school in Sofia (a general arts course, including architecture) and then moved to Prague to study theatre design.

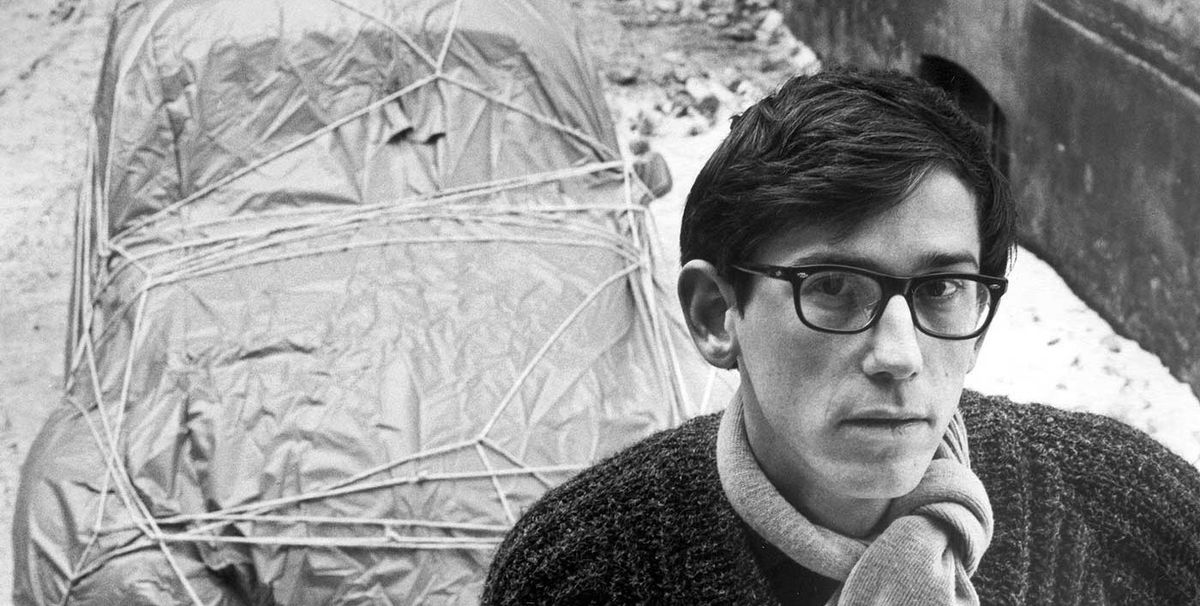

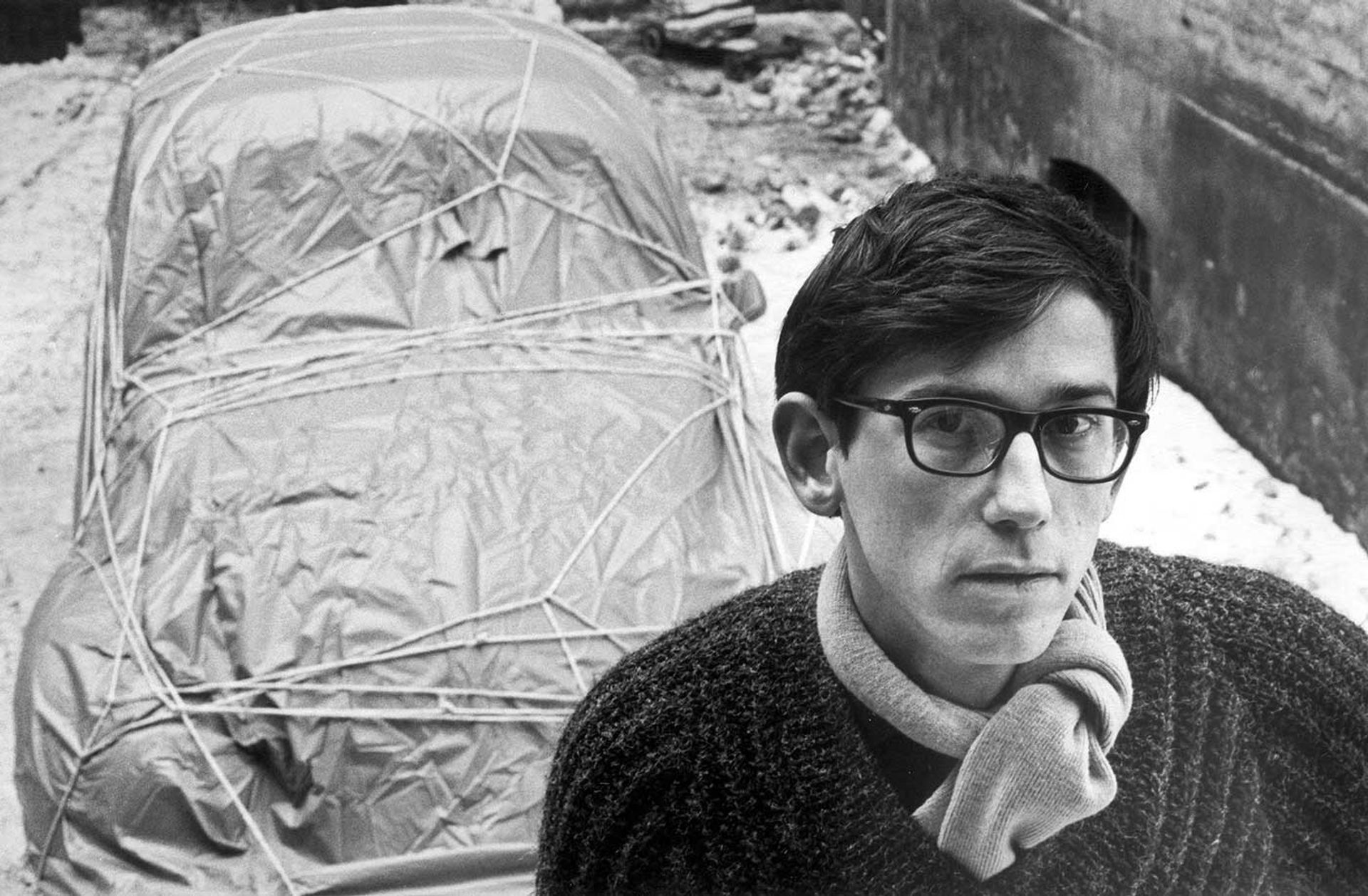

The artist with one of his earliest wrapped works, Wrapped Car (Volkswagen), which he produced in 1963 Charles Wilp; © 1963 Christo

He felt “suffocated under the horrible regime of the Soviets” and couldn’t wait to flee to the West. He escaped alone (“only speaking Russian and Bulgarian, not with any relatives, no cousins, no parents”) from Prague to Vienna, Geneva and then Paris where he met Jeanne-Claude in 1958. His first refuge, lent by someone working for the United Nations, was a maid’s room near the Champs-Élysées. He made a photomontage of the wrapped Arc de Triomphe as early as 1962.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude moved to New York in 1964, arriving on tourist visas and “disappearing into the crowd”. “For three years, we were illegal aliens,” he said proudly. They found a place to rent in Manhattan, eventually buying the entire five-storey industrial building in Howard Street, SoHo. And so, in what Christo referred to as “the city of refugees”, the building became their home—“our brain and the story of all our projects”.

The Pont Neuf Wrapped, Paris (1975-85) Photo: Wolfgang Volz

Every single fold

Christo characterised their artistic journey as “a thousand people who try to stop us, a thousand people who try to help us”. An important supporter was Michael Bloomberg, as mayor of New York in 2005, approving The Gates in Central Park after it had been refused three times (1981, 1985, 1987, Christo rattled off the dates). A resolute opponent was another mayor, Jacques Chirac in Paris, “the big opposition” to wrapping the Pont Neuf, first imagined in 1975 and finally realised in 1985.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude had a core “working family” of three: two nephews (one his, one hers) and Lorenza Giovanelli. She told me that Christo “never thought too much about death. He’d always look to the future.” Mock-up sections of the wrapped Arc were tested in Paris last October. Given that the project was supposed to happen this September, everything had already been decided before Christo’s death, Giovanelli said. He left precise instructions; he’d designed “every single fold of fabric, located the position of every rope, discussed every structural and technical detail with the engineers.” The project is now due to happen in 2021.

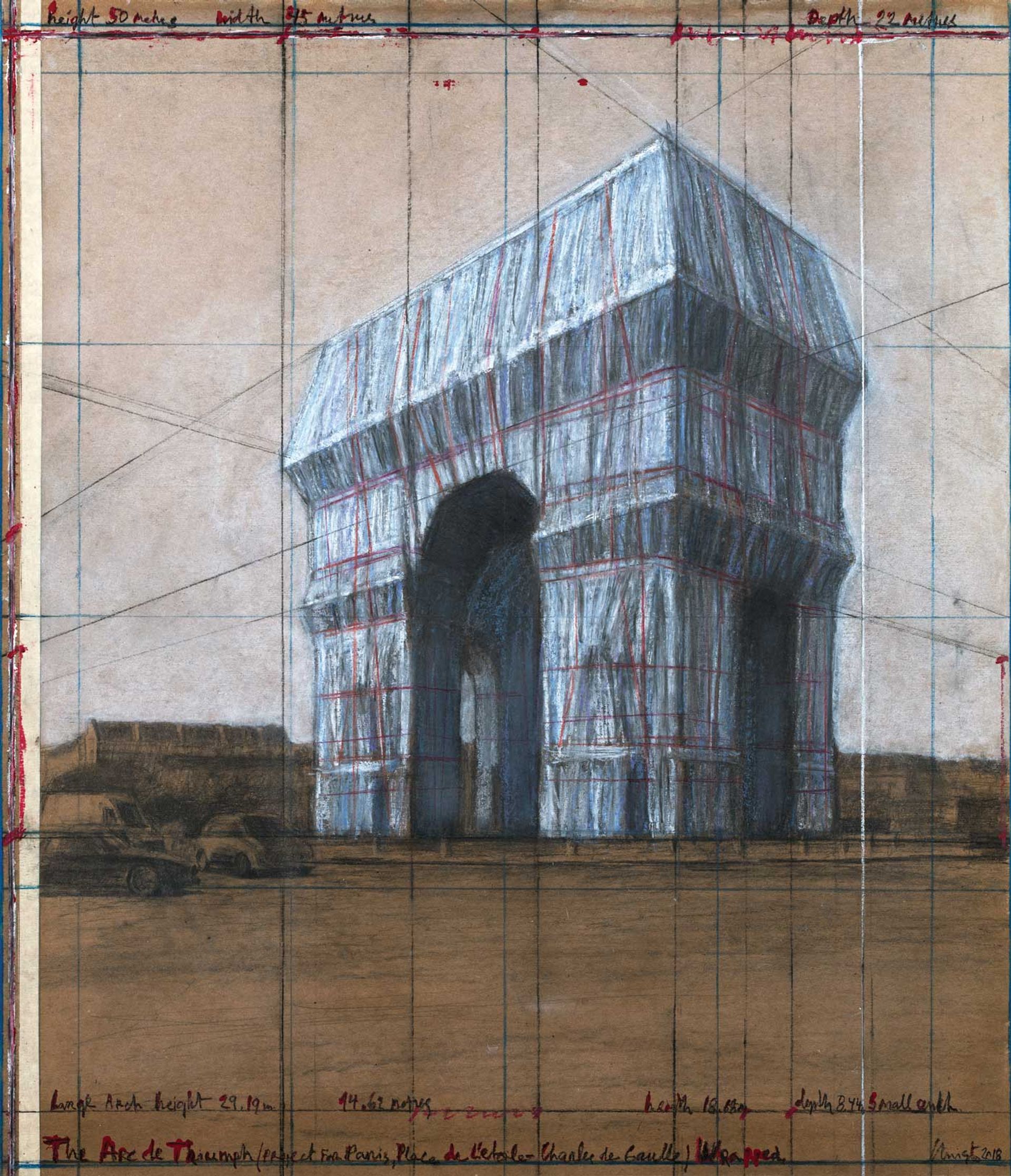

One of Christo's drawings, in pencil; charcoal; pastel; wax crayon; enamel paint and tape on brown board, for The Arc de Triumph (Project for Paris; Place de l'Etoile – Charles de Gaulle) André Grossmann; © 2018 Christo

During our final interview, Christo was clearly very excited by the Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped. He said that he’d never wrapped “an inner space” like this—“the cross of the four arches” with a non-stop wind blowing through. The fabric would be “like a living person”. He was thrilled by the prospect of seeing it.

Christo held up a sample square of his chosen fabric, a heavy German industrial textile, bright blue on the inside, silver on the outside. The coating is made of aluminium “to mirror the change of light”, he said. Unlike the Reichstag, the Arc de Triomphe is on a hill, with “an incredible, long perspective”.

“I am an artist who is totally irrational, totally irresponsible and completely free,” he said, almost gleefully. “Nobody needs my projects. The world can live without these projects. But I need them and my friends [do]”. Over time, some of us felt that we did too.

• Christo Javacheff (Christo), born 13 June 1935, died 31 May 2020