Riva Blumenfeld was an educator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for 16 years. She worked in three different lobes of the museum’s education department, leading tours for deaf visitors, teaching people with Alzheimer’s and more. She built relationships with her colleagues. It was not perfect: as a freelancer on contract, working a few days a week, she was not entitled to health insurance or other benefits. Her pay rate remained the same for eight years: $110 per session (of 60 to 75 minutes); when MoMA did grant a pay rise, it was a meagre bump of $5. But mostly Blumenfeld loved the job, which became part of her identity. “The department supported us unlike any other institution I’ve ever worked in,” she says.

Then, on 30 March—about two weeks after MoMA closed its doors due to coronavirus—she received an email telling her she no longer worked at the museum. It stated that because of the pandemic, her contract was terminated and that, although she would be paid for scheduled work in March, she should not expect to hear from the institution anytime soon. “When it is safe and feasible to reopen the museum, it will be months, if not years, before we anticipate returning to budget and operations levels to require educator services,” the email read.

“I was outraged,” says Blumenfeld. “My breath was taken away, because I’m proud that I’m a MoMA educator. How could you use that language?”

Months into a pandemic that has closed the doors of cultural organisations, the industry is facing an enormous crisis. A crowdsourced spreadsheet from March and April found that nearly 200 US institutions of various sizes had made cuts of all kinds, affecting thousands of people. Education has been a consistent target. In April, Brian Hogarth, the director of museum education programmes at Bank Street College of Education in New York, wrote a blog post asking “why education staff is, yet again, bearing the brunt of these layoffs”. The same month, more than 1,200 art historians, educators and curators signed an open letter calling on institutions to support educators.

Internally at MoMA, some staffers have made a show of solidarity with their freelance colleagues. In May, members of UAW Local 2110 union who work at the museum sent a letter to MoMA’s director, Glenn Lowry, stating that they “remain deeply concerned about the abrupt dismissal” of the educators and requesting that he commit to rehiring them as soon as possible. The letter was signed by 159 people from 26 departments. Lowry did not make that commitment in his response, focusing instead on the financial challenges the institution faces.

In a statement, a museum spokeswoman says that “MoMA has a fully staffed, diverse education department of 30 full-time staff and two year-long interns. There have been no layoffs or furloughs in the education department, nor any other department”. However, according to a Bloomberg report, MoMA has cut its staff from 960 to around 800. Wendy Woon, the longtime deputy director for education, has taken voluntary retirement. And several former MoMA educators who spoke to The Art Newspaper estimated that nearly 100 people received the email terminating their contracts.

“With the open-ended closure, there are no new contract assignments to offer to a group of excellent freelance professionals,” the MoMA spokeswoman said. “This work is not needed when the museum is closed; we truly hope that visitation and tourism will recover and once again drive the need for their services.”

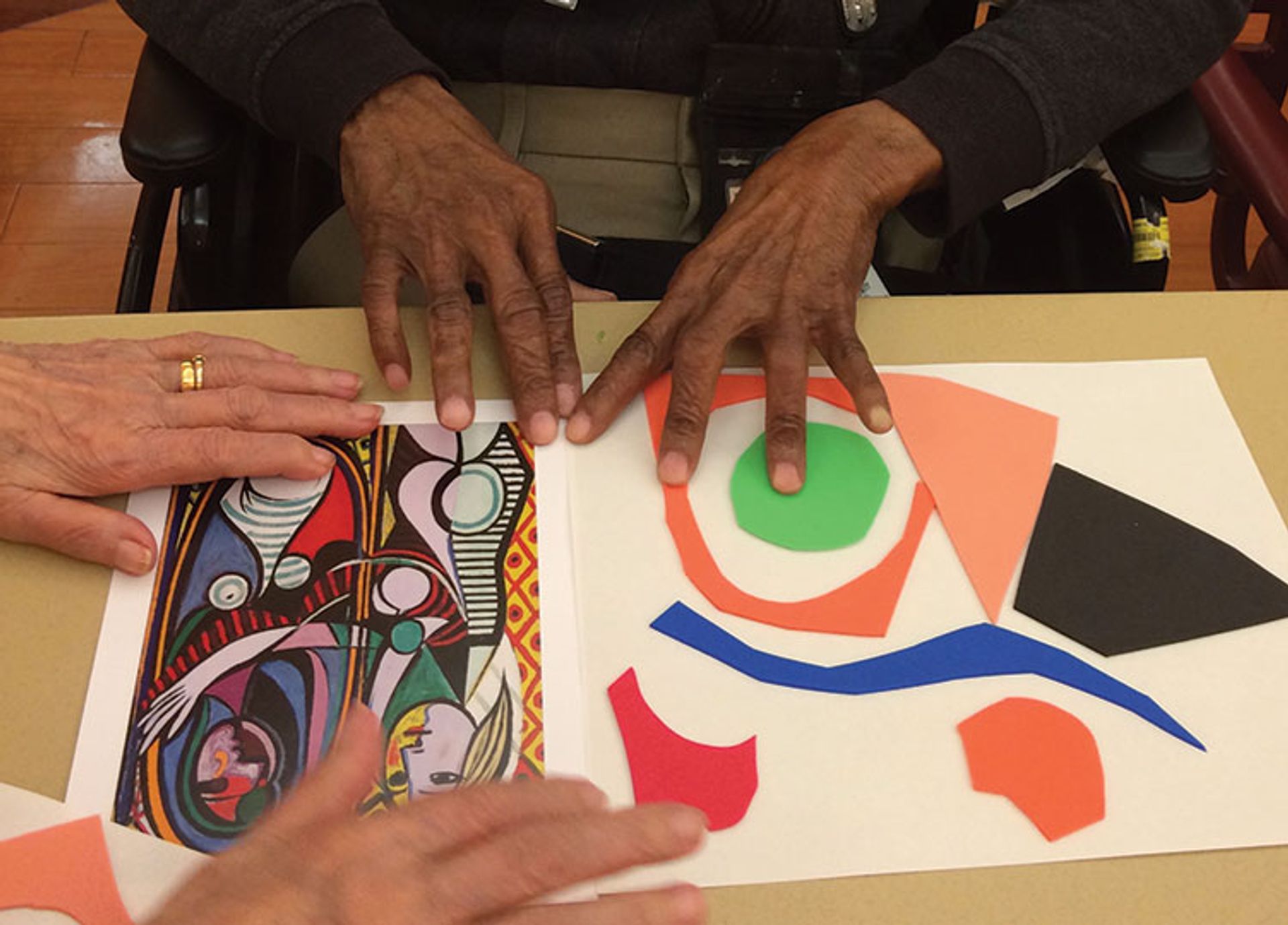

A community workshop at MoMA © Kerry Downey

“What they have is the bare minimum, the scaffold of an education department,” says Shellyne Rodriguez, an educator whose contract was cancelled in March. “If you don’t have educators, you don’t have a department. It’s like closing a school but the principal still shows up every day.”

MoMA was Rodriguez’s primary source of income. She worked there for eight years and, at the time of her dismissal, was managing 16 community partnerships with organisations such as Passages Academy, a school for students in juvenile detention. But she is not convinced that the museum’s top leaders valued what she did. “Like any nonprofit, the work that people do and the agenda of the institution don’t always match up,” she says. “They’re parading around pictures of this incredible work we do and the communities we serve, but at the end of the day, it’s the dollar [that matters].”

Money has been a major point of contention in the conversation about how cultural institutions have handled the pandemic. MoMA opened a $450m expansion last autumn and counts the billionaires Leon Black and Steven Cohen among its board members. According to its most recently available tax filing, it had an endowment of roughly $1bn in 2017, while Lowry’s total compensation was more than $2.2m. By contrast, according to one source, an education assistant receives $47,416.

The problem, however, is not solely economic: freelance educators tend to be more racially and ethnically diverse than the museums’ overwhelmingly white staffs. “I fear MoMA’s termination of educators reveals that diversity in the arts and cultural sector may be among the victims of this crisis,” wrote the Latinx studies scholar Arlene Dávila in the online arts publication Hyperallergic. As museums released statements in June supporting Black Lives Matter, critics challenged them on the gap between words and action.

“If Black Lives Matter is really a philosophy or way of existing in the world, then [it] starts within the institution you lead,” says the artist Camilo Godoy, who has been an educator at several New York City museums (though not MoMA) and recently compiled a set of documents to highlight pay disparities between management and education workers at six of the city’s institutions. “How am I supposed to read Glenn Lowry’s email about supporting Black Lives Matter when I know of a colleague whose contract was terminated and whose life did not matter for the institution in the most vulnerable moment of all?” he says.

Former MoMA educators also note that as artists, community organisers and activists, they brought alternative, dissonant points of view to a largely corporate institution. “We get to show kids something that matters to them,” says one, who asked to remain anonymous. “We get to teach them about a history and experience that represents the diversity of humanity, not just this super-fossilised, Eurocentric idea.”

Indeed, the issue of diversity extends beyond the educators themselves to their audience. Those dismissed by MoMA sustained connections with New Yorkers who might not interact much with the museum otherwise: school groups from the city’s outer boroughs, seniors, people with disabilities, undocumented minors. Kimberly Michaud, an art therapist at the nonprofit organisation Housing Works, says that her organisation’s long-running partnership with MoMA was deeply valuable to her clients, who have insecure housing and medical and mental health issues. “It’s as if you got a personal letter from Michelle Obama or something—like, how could they know me?” she says. “It’s a really special relationship.”

At stake is a crucial question: who is the museum for—tourists or locals, white folks or people of colour, wealthy crowds or low-income visitors? Through education, MoMA “created community,” says Blumenfeld. “Where the hell is that community now?”