Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-portrait, half-length, wearing a ruff and a black hat (1632), Sotheby’s Evening Sale, 28 July, £12m-£16m

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-portrait, half-length, wearing a ruff and a black hat (1632)

Fancy buying one of the last three Rembrandt self-portraits still in private hands? Sotheby’s is selling this one from a private collection on 28 July in its first mixed category evening sale. The painting has been dated to the end of 1632, when the 26-year-old artist set himself up in Amsterdam. He has made an effort for this one, with the ruff and fancy felt hat—it is one of only two self-portraits by Rembrandt in which he depicts himself formally dressed. Perhaps it is a form of business card—he wants to look the part—or, as it is relatively small, maybe there is a more romantic reason for his attire. It was painted at the same time as he was courting his future wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, so maybe it was a memento to send to her in Leeuwaerden, reminding her of what a catch he was.

Gustave Moreau, Hélène Glorifiée (1896), Mireille Mosler, $875,000

Gustave Moreau, Hélène Glorifiée (1896)

But if Rembrandt and his ruff are still a little dour for you, maybe this shimmering Symbolist depiction of a triumphant Helen of Troy basking in the adoration of her cast of admirers—warrior, poet, king and son—is more up your street. Moreau was a little obsessed with Helen of Troy—in 1854 he made an Abduction of Helen in the style of Poussin. This watercolour and gouache, Mireille Mosler writes, “marks the culmination of Moreau's developing thoughts on, and ambitions for, this topic” with Helen “depicted as equally fatal, but less malevolent than in the other pictorial incarnations; a mysterious enchantress who captures all mankind in her spell”.

James Ward, Worthy, a Thoroughbred Hunter (1823), Stuart Lochhead Sculpture, £325,000

James Ward, Worthy, a Thoroughbred Hunter (1823)

Worthy, meanwhile, is basking in the adoration of his proud owner, William Wigram, who would have commissioned James Ward to paint this portrait. Wigram might have been adoring, but the white marks on Worthy’s spine and ribs (common in horse portraits of this period) would have been caused by sores from a badly fitting saddle and overuse of spurs. Slightly younger than the better-known George Stubbs, though arguably no less talented, Ward is best known for his paintings of animals. The painting was passed down by descent until 2010 when it sold at Christie's in London and was bought by the London-dealer John Mitchell. Mitchell in turn sold it to the private collection where it has remained until now.

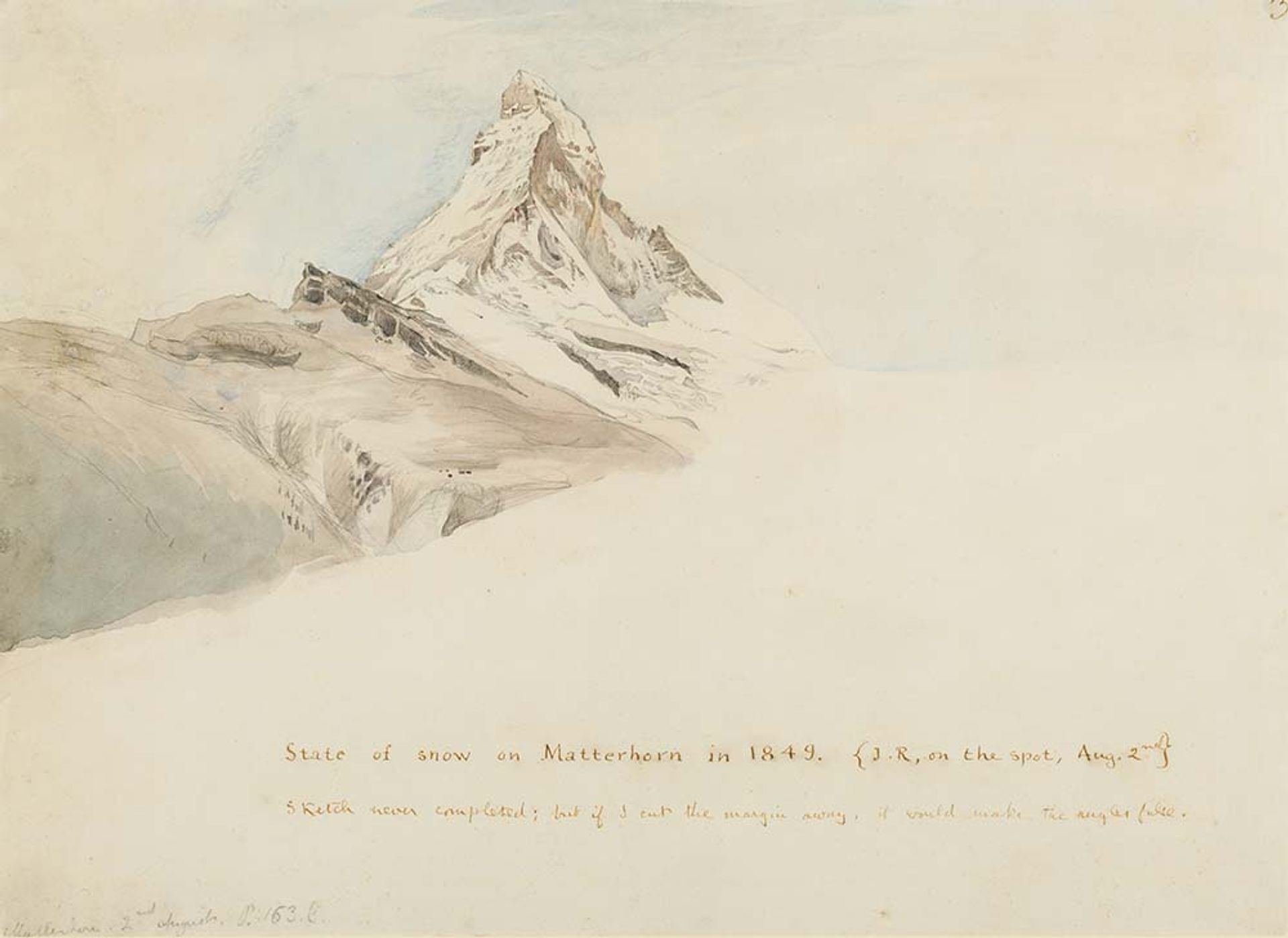

John Ruskin, The Matterhorn from the north-east, Switzerland (1849), Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, £75,000

John Ruskin, The Matterhorn from the north-east, Switzerland (1849)

This spare but beautiful watercolour over pencil of the Matterhorn by John Ruskin was never finished. Perhaps the weather took a turn, or Ruskin simply got too cold. He has annotated it though: “State of snow on Matterhorn in 1849. {J.R, on the spot, Aug. 2nd}. Sketch never completed; but if I cut the margin away, I should make the angles false.” The watercolour has been illustrated in several books and was given by Ruskin to his Drawing School Collection at Oxford—although he took it back in 1887. It was bought by the current owner in 2007 at Christie’s.

Thomas Rowlandson, Lord Thurlow, the Lord Chancellor, Twitching a Startled Horse (late 1780s), James Mackinnon, £11,000

Thomas Rowlandson, Lord Thurlow, the Lord Chancellor, Twitching a Startled Horse (late 1780s)

More equine trivia—here the then-Lord Chancellor is shown twitching a frightened horse by twisting its ears. Twitching is a way to calm down a horse, and the old-fashioned method of twisting its sensitive ears is now considered cruel by many and has largely been replaced by lip twitching. That aside, it’s hard to work out quite why Rowlandson, the famed Georgian caricaturist, has chosen to depict the Lord Chancellor twitching a horse. But the dealer James Mackinnon has a theory: “Thurlow had two illegitimate daughters by a Mrs. Hervey, one of whom eloped to Gretna Green and was hotly pursued by her father, who was deeply fond of the girls. Father and daughter were later reconciled. The incident portrayed may relate to this pursuit or to some other unidentified moment.” Horse as a metaphor for a headstrong daughter, perhaps.

Maioliche Artistiche Cantagalli, Maiolica ewer in the form of a dolphin (late 19th century), Raccanello Leprince, £3,000

Maioliche Artistiche Cantagalli, Maiolica ewer in the form of a dolphin (late 19th century)

London Art Week is not just about paintings and works on paper. Three-dimensional works of art feature too, such as this dolphin ewer exhibited by Raccanello Leprince, consisting of Camille Leprince and Justin Raccanello who are on a mission to make Renaissance ceramics appeal to a modern audience. Maiolica is a form of Italian tin-glazed earthenware, made in the late medieval and Renaissance periods and of a form that originated in Spain. Majolica, on the other hand, was made in the 19th century and is lead-glazed earthenware. This form of dolphin ewer was made after an Urbino model in the Bargello museum in Florence.