Buoyed by successful efforts to conserve outdoor murals by Keith Haring elsewhere, conservators are hoping that the recent easing of European travel restrictions will enable them to begin work in coming months on one in Amsterdam that has experienced significant paint losses since the artist created it in 1986. The mural has been the focus of a local campaign calling for its restoration since it was uncovered in 2018.

Haring, known for his fervent commitment to making his graphic art as accessible to the public as possible, painted the mural while in Amsterdam for his first solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. In typical fashion, “he was just in a sort of frenzy of painting, and it’s like, ‘Somebody find me a wall!’” says Will Shank, an independent US conservator who hopes to restore the mural with his Italian colleague Antonio Rava in a four-to-six-week project.

A suitable brick wall was found in 1986 on a building that was then used as a Stedelijk art depot in the grounds of the city’s Central Market Hall. “Then he’d say, ‘Someone find me some paint!’” Shank recounts. For his outdoor murals, Haring spontaneously relied “in good faith” on whatever commercial paints became available—in this case, an oil-based alkyd paint that “doesn’t have a good track record for enduring outdoors”, the conservator adds.

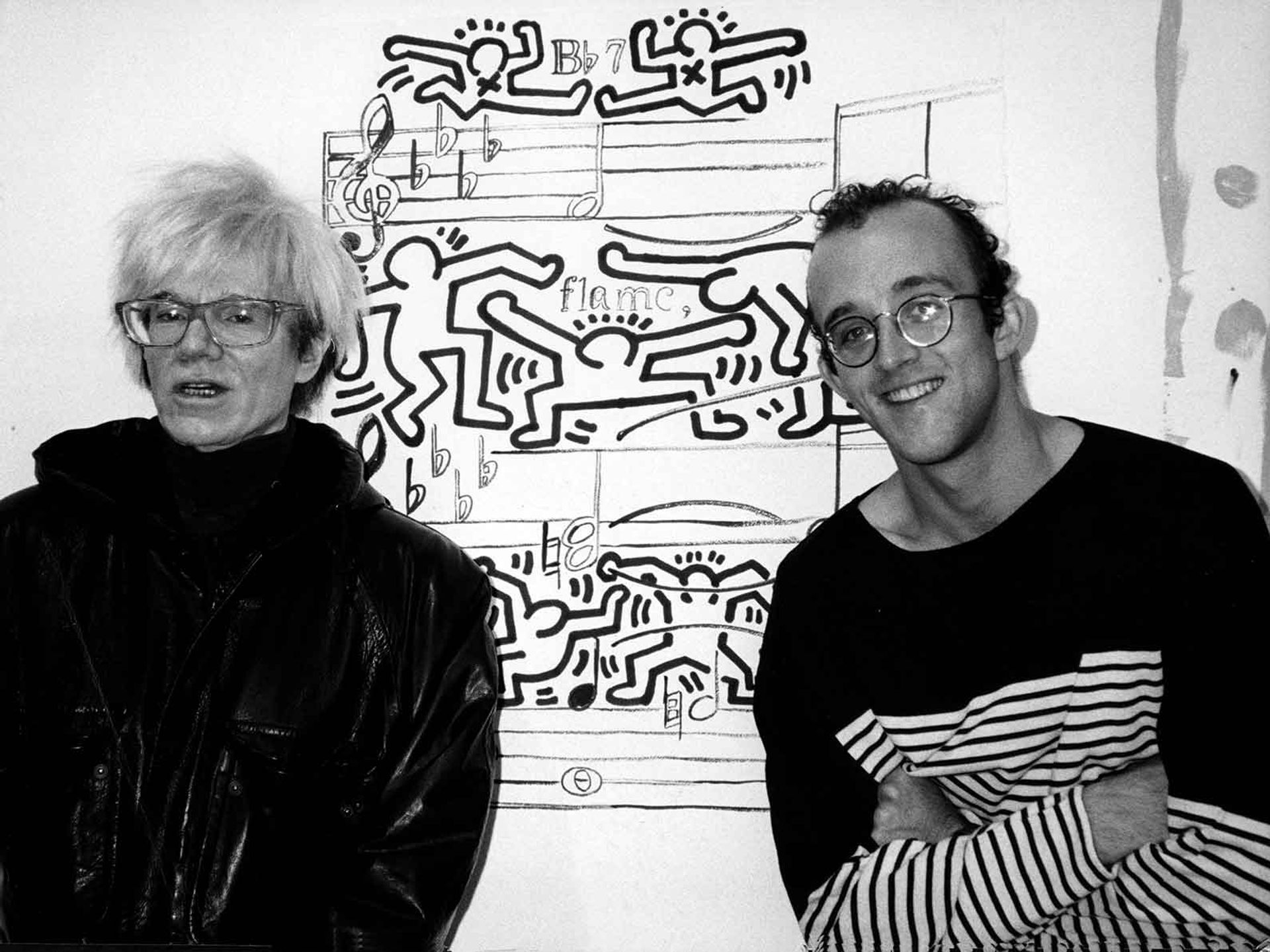

Keith Haring with Andy Warhol in 1986 Photo: Keystone Press/Alamy

Haring painted directly onto the brick in a titanium white line without any preliminary sketches, beginning at the top right and gradually working his way down to the lower left, Shank says. The image, measuring around 12m by 15m, is a highly unusual one within the artist’s opus: a creature with a dog’s head, a caterpillar’s body, human arms and a fish tail, with a person astride its back. “His line was just so self-assured—he didn’t make mistakes,” says Shank, who has also restored deteriorating Haring murals in Paris and Pisa.

Nonetheless, “some people mentioned what a difficult time Haring had getting the paint to stick to the wall because it was blustery and wet”, Shank says. As a result, about 20% of the white line that Haring painted has not adhered and will have to be inpainted, he estimates. Compounding the challenge, the wall is made of two kinds of bricks—red and yellow—and the yellow ones are less porous and have retained less of the paint. “We will experiment on the scaffolding with different kinds of paint to make sure that it does stick to both kinds of bricks,” Shank says. (Rava assumes that they will end up using an acrylic variety.) A protective coating of hydrorepellent resin will then be applied to protect the line of white paint from rain, grime and ultraviolet light.

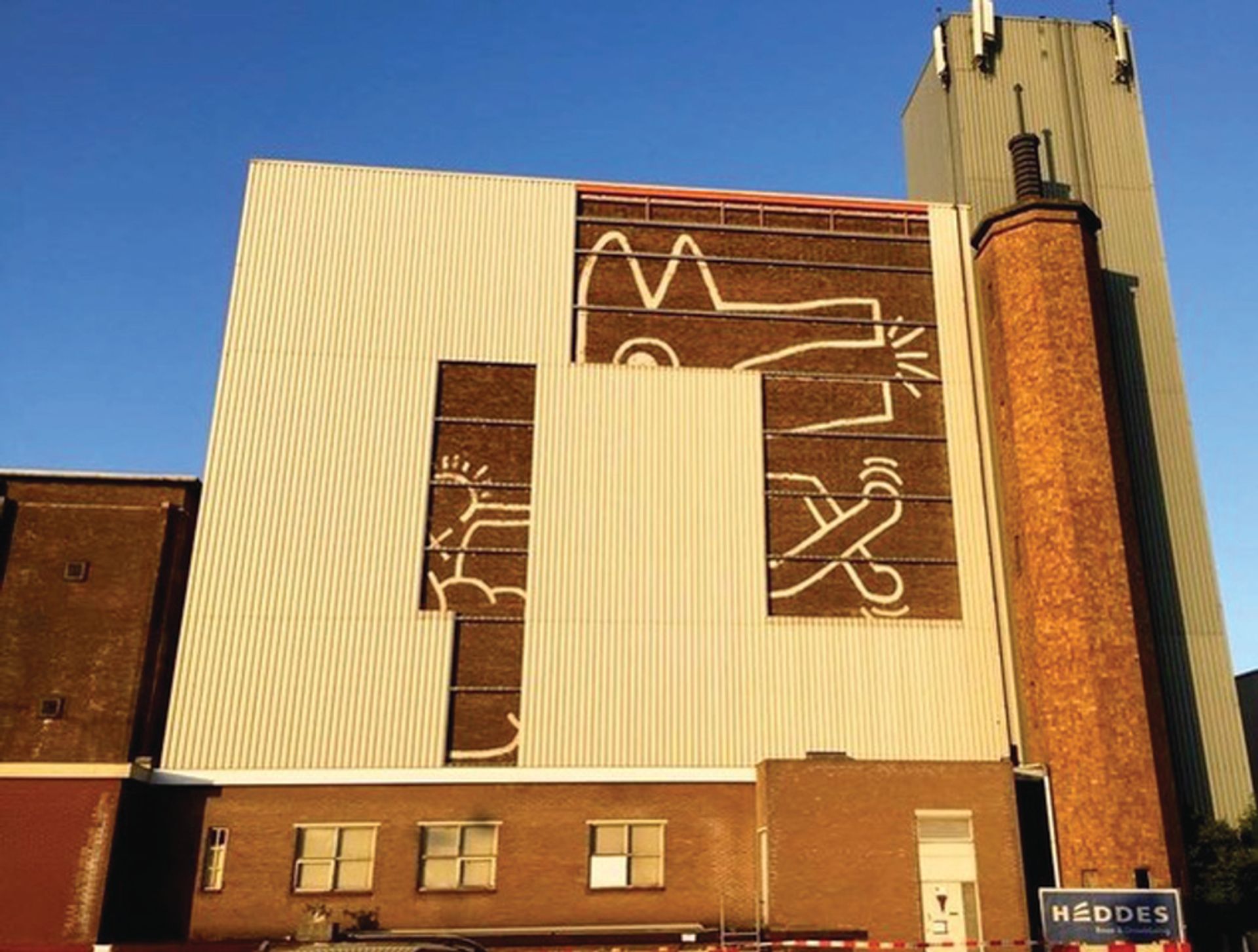

The aluminium cladding on the food depot building was removed in 2018 Photo: Philip van Maanen. Artwork: © Keith Haring Foundation

In 1994 the building changed hands and became a refrigerated food storage facility, which led to the covering of the exterior with an aluminium façade that completely obscured the mural. Despite some paint losses, “The metal screen did mostly protect it from the rain and the insects and the birds” for the next two-and-a-half decades, Rava says.

Interest in the work resurfaced in 2014 when the Dutch graffiti artist Aileen Middel, aka Mick La Rock, came across a photograph of it and wondered how it had fared. Eventually joining forces with the Keith Haring Foundation, the art dealer Olivier Varossieau and the Stedelijk Museum, she led a campaign to organise the removal of the panels in 2018.

People in Amsterdam said: 'Give us our mural back'Will Shank, project conservator

The costs of the €180,000 restoration are being footed in equal parts by the Haring foundation, the municipality of Amsterdam and Marktkwartier, a real estate collaboration between Ballast Nedam Development, part of Rönesans Holding, and VolkerWessels Vastgoed BV, which owns the building in the city’s Food Center area.

“What I think is really cool about this project is that it was instigated by a grassroots effort,” says Shank. “People in Amsterdam said: ‘Give us our mural back.’ They made sure that the owners knew what a treasure they had.”