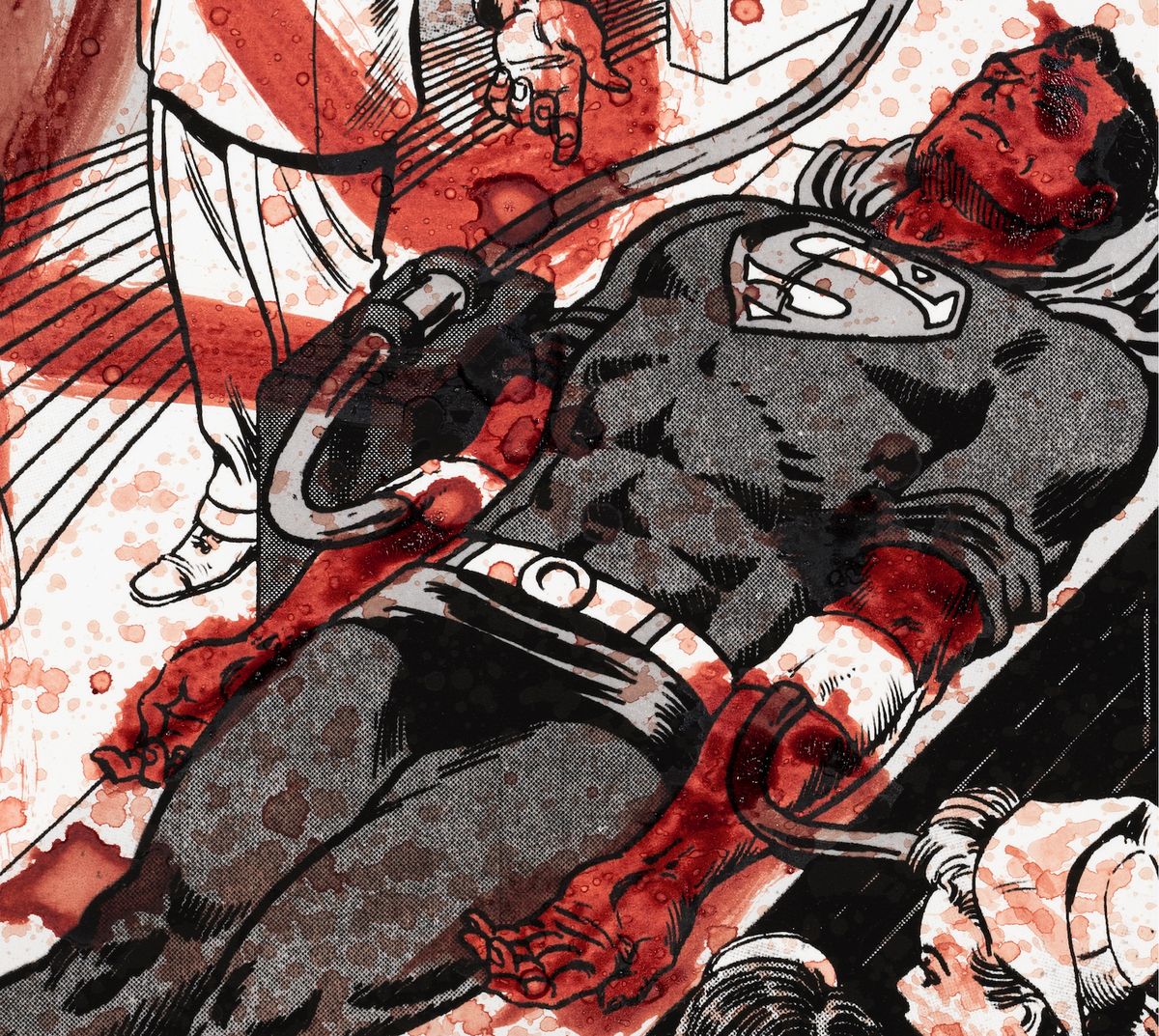

In honour of Pride month, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York is hosting the online exhibition Can You Save Superman by the New York-based artist Jordan Eagles, which addresses the US Food and Drug Administration’s history of discriminatory policies against the LGBTQ community. In 1983, the organisation implemented a lifetime ban on blood donations from gay and bisexual men, and this year revised the policy to three months—a policy that stands even in light of “massive blood shortages due to the Covid-19 pandemic”, the artist says. The show, curated by Eric Shiner, contains a series of mixed-media works made on large-scale prints of appropriated comic book strips from Attack of the Micro-Murderer, a 1971 comic in which a dying Superman calls on the citizens of Metropolis to donate their blood in order to save him. The works have been soaked with the blood of a gay man prescribed to Prep, a medicine that can reduce a person’s chance of contracting HIV and make the virus undetectable in their bloodstream.

The GLBT Historical Society Museum in San Francisco traces the history of the rainbow flag and its creator in the show Performance, Protest and Politics: the Art of Gilbert Baker. The rainbow flag has now become such a ubiquitous symbol of the LGBTQ community but was only conceived as such in the late 1970s, when the late Kansas-born artist and activist Gilbert Baker created a colossal eight-colour rainbow flag for the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade. Although the flag existed before a symbol of peace, among other things, Baker’s iteration, which he hand-dyed and stitched with strips of muslin, assigned each of the eight colours a different meaning, such as green for nature, yellow for the sun and pink for sex. The original flags for the parade were lost, but a widely adopted symbol was born. The flag was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2015. In an interview with the museum, Baker says that flags are a proclamation of power, and that he wanted to create something that represented the gay community as a “people and a tribe”.

The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York has digitised several works in the exhibition Salman Toor: How Will I Know that give viewers insights into the artist’s unique queer sensibility. The New York-based artist’s first museum closed early due to the coronavirus pandemic and includes paintings like Bar Boy (2019)—showing lonesome, young gay men draped around each other in a nightclub—and a languorous youth making video calls in the nude in the work Bedroom Boy (2019). The artist’s later paintings “echo his own experience as a queer Brown man living between the United States and South Asia”, writes Ambika Trasi, a curatorial assistant of the museum, adding that Toor’s paintings “are ruminations on the identifications variously imposed on and adopted by queer South Asian men living in the diaspora”. Visitors to the Whitney will hopefully be able to seek out in person Toor’s painterly exploration of queer diasporic identity before too long.