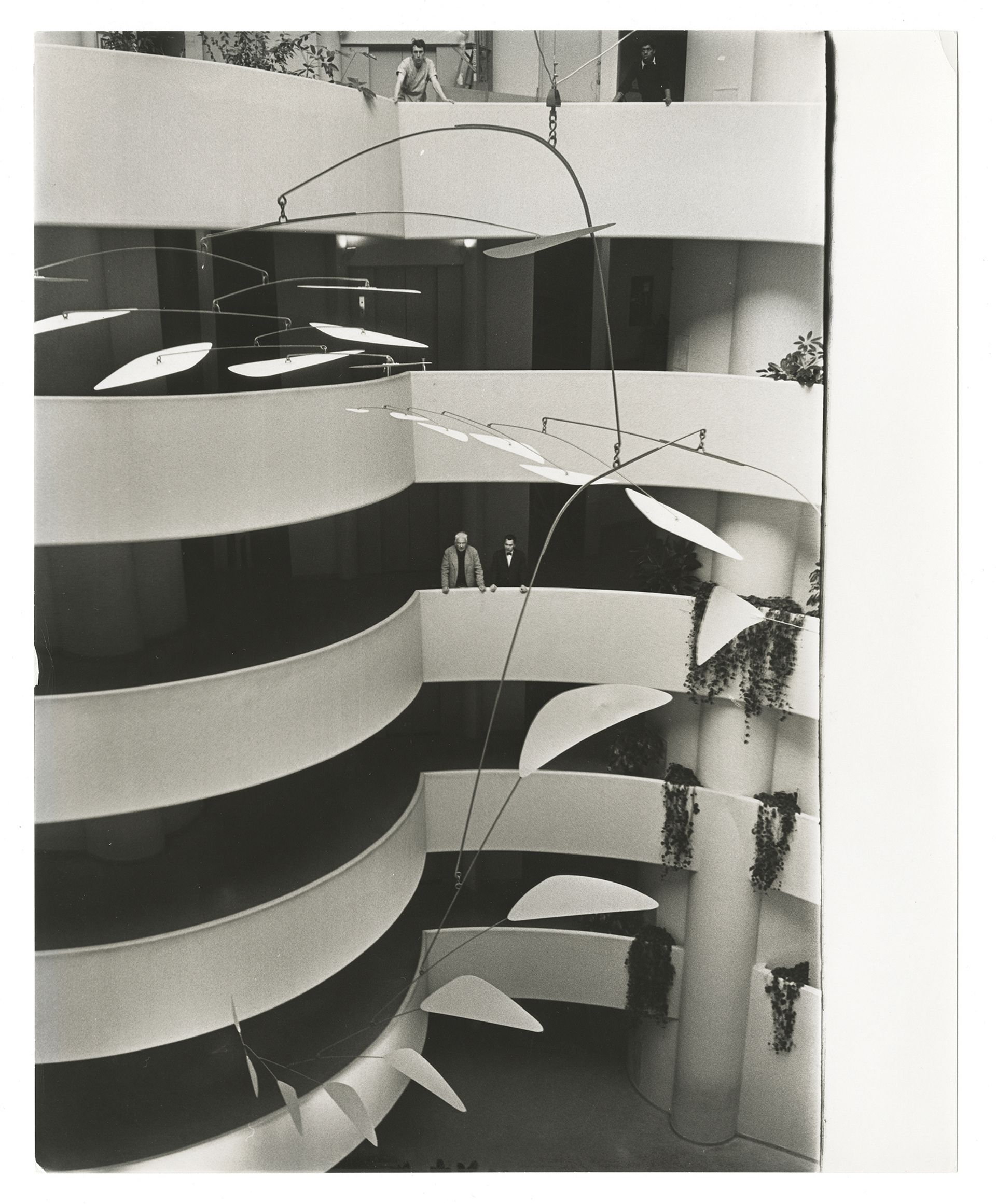

In 1964, families piled into the Guggenheim Museum’s spiral for an exhibition of Alexander Calder’s work. “My fan mail is enormous,” said Calder, who was 66 at the time. “Everybody is under six.”

Calder (1898-1976) was popular. After the beating that his mobiles got from those Guggenheim crowds, museums began to put “do not touch” signs by those works. The signs weren’t just for children. A photo in Jed Perl’s massive biography shows grown women blowing on his mobiles. The art wasn’t just fun. If you touched it, you could make it move.

A long readable ride, Calder: the Conquest of Space: the Later Years 1940-1976 tracks the artist’s life and works from his return to the US before the Nazi invasion of France to the commissioning of massive sculptures for public spaces around the world. This erudite, wide-ranging biography’s first volume, Calder: the Conquest of Time: the Early Years 1898-1940, followed an American engineer, the son and grandson of sculptors, as he imagined and fashioned sculptures whose form was not locked into a single moment.

Perl places the man in his moment in the history of sculpture: “No longer were the figures in a painting or a sculpture what really mattered. Now what mattered was the life of the work of art itself. For Calder, this meant the object had to take on a life of its own. Calder’s objects began to move. At first the movement was driven by a crank or a motor. Pretty soon it was wind-driven. Eventually he moved his objects out of the studio and into the world. His mobiles and ‘stabiles’, from the Lilliputian to the gargantuan, commanded time and space in ways sculpture never had before.”

An installation photograph showing The Ghost (1964) at the show Alexander Calder: a Retrospective Exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York in 1964 Photo: © Calder Archive

Part of getting there involved the trial-and-error creations of a charming bear of a man who cracked jokes as he worked with his hands. Another part involved the experiments of a visionary on the frontier of the artistic imagination. The achievements of these stout volumes is that Perl gives us the man in full, a description that Calder, who loved to eat and drink, might have enjoyed.

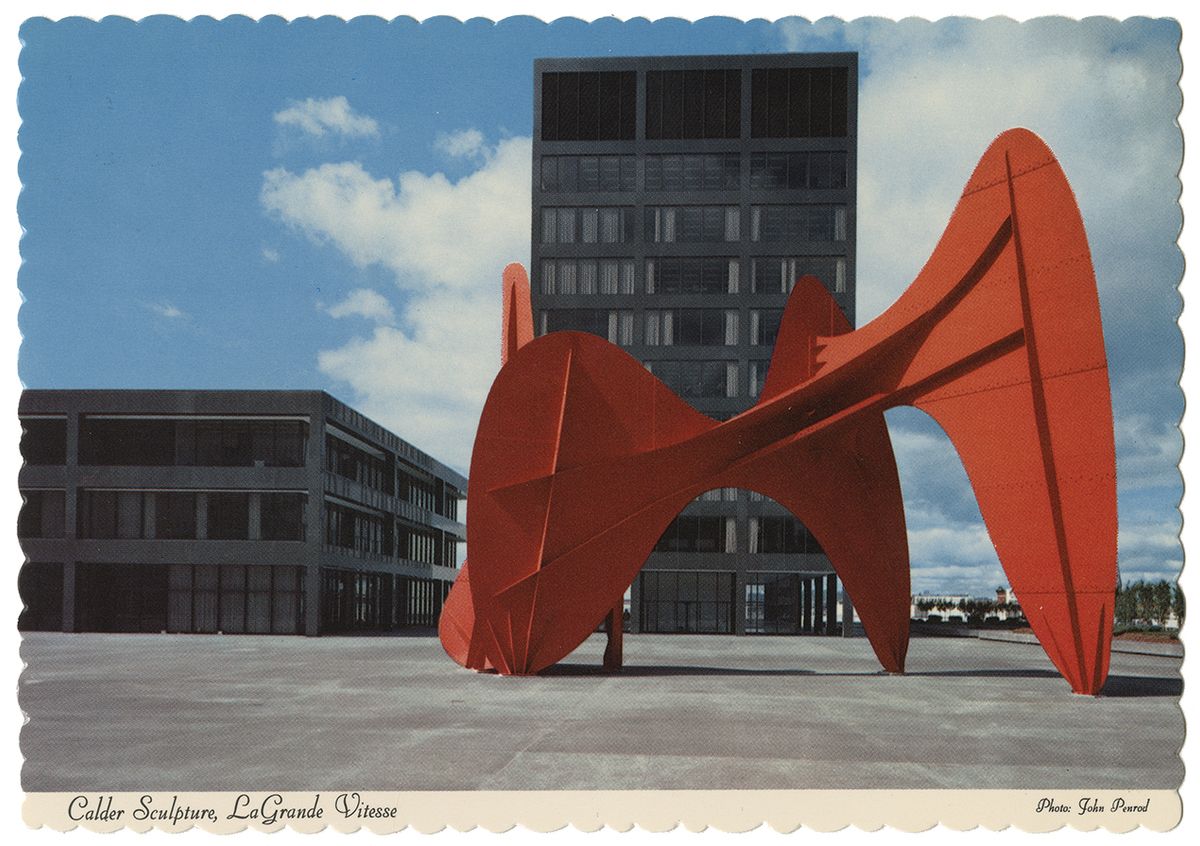

Vivid in its evocation of people and works of art, volume two begins with Calder in Grand Rapids, a rich, conservative city in Michigan, as he christened his enormous curvy sculpture, La Grande Vitesse, in 1969. Calder, by then a celebrity, was bringing abstract art—with a French title, no less—to Republican heartlands, with some help from the federal government. It was no small feat then, when abstraction was almost as loathed as Communism.

Perl then rewinds to 1940, when the sculptor quit Paris for the US, building a public and a market back home, fretting over money and fighting despair among displaced Europeans like André Masson and Marcel Duchamp. Calder would continue to make mobiles (shown at his Museum of Modern Art retrospective in New York in 1944), but he was shifting toward sculptures that stood firmly on the ground, hence the name stabiles.

Once the war ended, Calder left his dealer Pierre Matisse for a new one, Curt Valentin, and his champions soon included everyone from Jean-Paul Sartre to the playwright Arthur Miller. As Calder’s work grew in size and ambition, not all critics admired him. Clement Greenberg, who preferred tough and brooding Abstract Expressionists, faulted his “cheerful” affability. (In a pairing of a Calder figure and one painted by Jackson Pollock, Perl reveals some similarities.) Another critic, at Calder’s 1964 Guggenheim show, wrote, “his exhibition is enchanting, if you don’t stop to look”.

Calder liked the crazy luxuriant excess, the impossibility of disentangling the beautiful and the bizarre

Looking hard (past the “aw-shucks” exterior), Perl finds a Calder who was well-read, sophisticated and hard-headed, inspired by Mondrian and Matisse, and enlivened by his peer Joan Miró. He was also deeply influenced by the fantasies of Hieronymus Bosch, one of Surrealism’s godfathers, as Perl shows with some revealing comparisons. “Calder liked the crazy luxuriant excess, the impossibility of disentangling the beautiful and the bizarre,” Perl writes. “From Bosch, he gleaned a new idea, an idea of invention gone berserk.”

Calder himself drank and dined with André Masson, André Breton and others whom he dubbed “sewer-realists”. As with much of the art he saw around him, praise was rare, and any effects on his own work were hard to measure, literally. If Calder were ever part of a movement, it would have had to bear his own name, and he would have been the last to put it there. Yet there was a Calder effect. We see it in young Ellsworth Kelly’s abstractions and in architects who transformed urban spaces, everywhere from Rio to Chicago, to accommodate the scale Calder demanded.

Perl ends his book with the ailing Calder’s death at 78 in 1976 from a heart attack in Greenwich Village while the Whitney was honouring him with a retrospective. Hilton Kramer had just been unusually generous with praise: “His great distinction was to introduce an element of wit into the solemnities of Constructivist art at the same time that he literally set it in motion.” In two substantial tomes, little is said about Calder’s influence on artists and critics in the generations after 1976. There’s plenty to write about that in another study.

Jed Perl, Calder: the Conquest of Space: the Later Years, 1940-1976, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 688pp, $60(hb)

• David D’Arcy is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper based in New York